Beside the great Lake Kivu, beneath the shadow of an enormous volcano, the Rwanda-DRC border divides the neighboring cities of Gisenyi and Goma. As the day begins, the predominant impression is one of movement, as people walk in either direction through the customs checkpoint, carrying giant bunches of green banana, stacks of nesting plastic chairs, anything that is tradable. They form an unbroken stream of humanity crossing to and fro, the tall border signboards towering overhead.

With trade and labor mobility across national borders comes the heightened risk of disease. We are in Gisenyi, on the Rwanda side of the border, to visit a project that is working to detect and arrest the spread of dangerous diseases like ebola, tuberculosis, and cholera. In the past, vulnerable border areas have lacked the capacity for the kind of rapid diagnosis that is needed to check epidemics. Later in the day, when we visit a village about 40 kilometers from Gisenyi, it is obvious that this is changing.

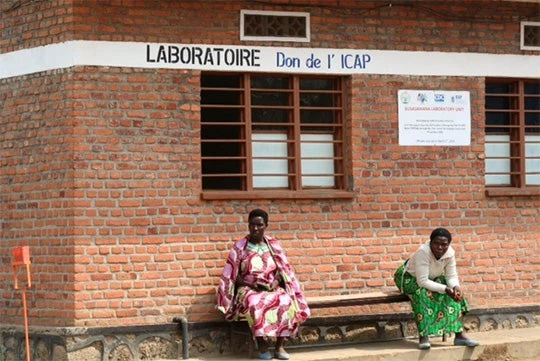

At the Busasamana health center, the small laboratory is one of several that are networked across five countries—Burundi, Kenya, Uganda, Rwanda, and Tanzania—participating in the East Africa Laboratory Networking project. The project is a World Bank-supported effort to strengthen diagnostic laboratories, a vital but long-neglected pillar of the average public health system.

Here we meet Jean Claude Iyakaremye, an agricultural worker who fell gravely ill while working on a farm across the border in the DRC. He was brought to the health center, where his condition was identified as cholera and treated immediately. Quick community outreach in the surrounding villages ensured that a few more cases were identified and nobody died needlessly from the treatable disease.

Disease samples needing more sophisticated diagnosis—for example, suspected cases of tuberculosis—are sent in a cool flask to the District Hospital in Gisenyi, where a large modern laboratory is being built. Meanwhile, the existing laboratory is housed in a makeshift building, but has begun to follow the protocols required to be an “accredited” laboratory. Its diagnostic capacity has been greatly increased, with many samples no longer having to be sent to Kigali for analysis.

The laboratory technicians in Gisenyi are clearly proud of the progress they have made and are keen to show us how things have changed. In a part of the world with migrant labor and at risk of TB-HIV co-infection, the laboratory protocol being learned and practiced here, and the modern diagnostic equipment could indeed mean the difference between life and death to many.

An interesting feature of the five-country project is that each country specializes in a particular area and shares knowledge with the others. Rwanda’s specialization is in Internet and Communication Technology (ICT). The computer specialist at Gisenyi hospital shows us the upgraded technology that has come to the hospital as a result of the project. Rwanda is using this opportunity to upgrade ICT systems at the whole hospital, and not just in the laboratory.

Driving out of Gisenyi that evening along winding mountain roads, I thought of all the development that has been possible in the surrounding district of Rubavu as a result of peace. One might think of it as a peace dividend—the building of institutions, systems, infrastructure, and human capital that follows the ravages of conflict. Access to good services is an essential element of sustaining that peace.

Join the Conversation