Make a bet: Will we celebrate the achievement of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in 2030? Or will we analyze why the world community fell short of its ambitions?

A possible answer is that we will lack the data to do either.

The 17 SDGs lay out a uniquely ambitious and comprehensive agenda for global development until 2030. However, achieving these goals is not the only challenge. Monitoring progress towards these goals represents an enormous task for countries’ statistical systems.

The SDGs include 231 indicators for 169 targets. The data requirements for the 60 indicators of Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), the SDGs’ predecessor, were modest in comparison. Yet in 2015, the target year of the MDGs, countries reported on average data on only 68% of the MDG indicators.

Increased Data Requirements by SDGs

The SDG indicators are not only more in numbers, they are also more complex. Here is one indication: When the global indicator framework for the SDGs was adopted by the UN General Assembly in 2017, 84 (36%) out of the 231 indicators did not have any internationally established methodology or standards. It is only since last year, that thanks to a major effort by the global statistics community, the Inter-Agency and Expert Group on SDG indicators considers the methodological development sufficiently advanced for all of the indicators to be tracked.

Yet, the availability of standards does not equal the availability of data. In fact, most countries’ statistical systems appear to be struggling to provide data on SDG indicators. The international community managed to address methodological gaps in measurement in record time—a similar commitment is now needed to fill data gaps.

As part of the 2021 World Development Report: Data for Better Lives, the World Bank recently launched the Statistical Performance Indicators (SPI). The SPI assess the performance of countries statistical system across five pillars: (i) data use, (ii) data services, (iii) data products, (iv) data sources, and (v) data infrastructure. In this blog post, we explore the pillar on data products, which draws on the UN SDG database and OECD data to track countries’ data reporting on SDG indicators.

There are serious data gaps in assessing country-level progress towards SDGs. On average, countries had reported one or more data points on only 55% of the SDG indicators for the years 2015-2019. No country reported data on more than 90% of the SDG indicators, while 22 countries reported on less than 25% of the SDG indicators.

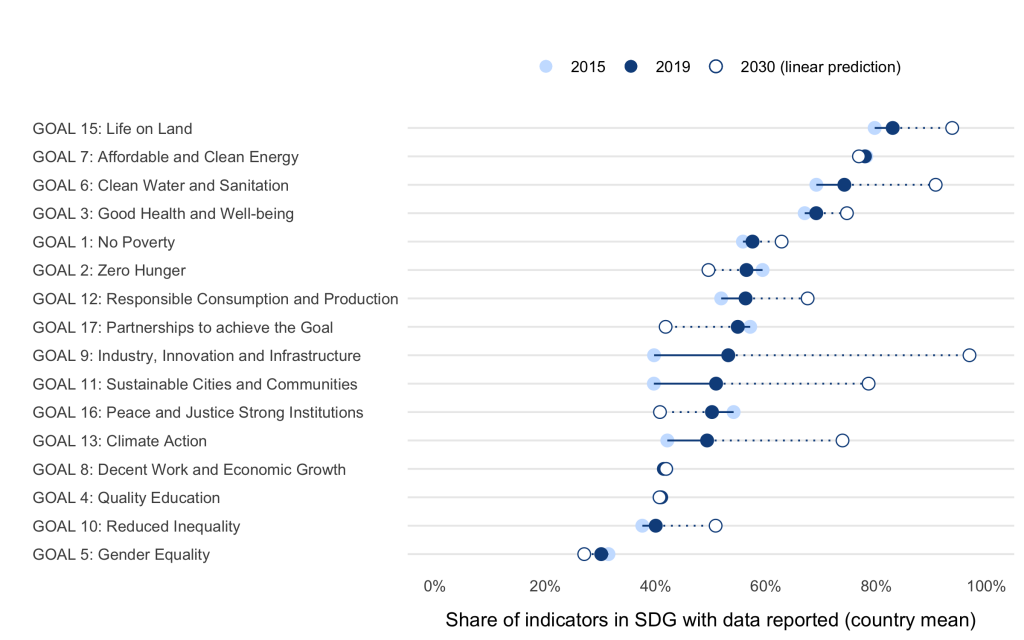

The good news is that countries improved their data reporting on most SDGs in recent years. For 10 out of the 16 goals analyzed, countries reported more data for 2019 than for 2015. And for some goals for which countries previously reported little data, the progress was particularly strong. For example, average reporting on industry, innovation, and infrastructure (goal 9) improved from 40% to 53%. But also on environmental SDGs, for which countries had already reported relatively more data, there were further improvements.

Progress on SDG Data Reporting (2015-2019)

We exclude values that were produced by an international organization through modeling. We do include values that are either country reported, country adjusted, estimated, or are included as global monitoring data. Goal 14 is not included as land-locked countries don’t report on it. The predictions are based on linear models estimated by OLS on all data points from 2015 to 2019.

The not-so-good news is that the current pace of progress on SDG data reporting is likely insufficient. Fitting a linear trend on the data from 2015 to 2019, we find that for no SDG, we would expect countries to report data for all indicators. Data on gender equality are particularly scarce. And these predictions do not account for the Covid-19 pandemic, which disrupted routine data collection efforts and delayed censuses and surveys—with negative effects on data availability and quality in the years to come.

Analyzing country performance, we also find that income is not as strong as a predictor of SDG data reporting as one might expect. In fact, based on the UN SDG database, high-income countries are trailing low- and middle-income countries. The effect is partly driven by small, high-income island states and, to a lesser extent, oil-producing countries in the Middle East. However, even if we restrict the sample to the 159 countries with a population larger than a million, high-income countries perform only on par with lower-middle income countries.

Unlike the MDGs that focused on developing countries, the SDG are universal and apply to all signatories. Not every indicator may be relevant for all countries, but the SDGs are global goals for global challenges, with many topics of direct relevance for wealthy countries. For example, high-income countries reported a mere 25% of the indicators on gender equality (goal 5). Ending discrimination and violence against women (targets 5.1 and 5.2), ensuring women’s equal opportunities for leadership (5.5), and universal access to sexual and reproductive health (5.6) can hardly be considered priorities for low-income countries alone.

SDG Data Reporting by Income Level (2019)

Another indication that SDG data reporting may not only be a function of statistical capacity but perhaps also of political will is that the correlation between pillar 3 of the SPI, which measures data reporting on SDGs, and the other pillars of the SPI is lower than the correlation between the other pillars. Put differently, statistical systems that, for example, draw on a variety of data sources (pillar 2) also tend to have a strong data infrastructure (pillar 4, correlation 0.74) but do not necessarily also report a lot of SDG data (pillar 3, correlation 0.46).

It is possible that some countries collect data on more indicators than they submit to the UN SDG database. Note, however, that for OECD countries, we supplemented the UN SDG database with comparable data submitted to the OECD following the methodology in Measuring Distance to the SDG Targets 2019: An Assessment of Where OECD Countries Stand.

The value of reporting SDG data goes beyond monitoring progress. Previous research suggests that countries’ performance on measuring progress towards the MDGs was positively correlated, if not causally associated, with actually making progress on the goals—suggesting the old management mantra “what gets measured gets done” might also apply to the international arena. By keeping track of what gets measured, the SPI can help countries shed light on where they fall short on SDG reporting, and, ultimately, where they still have work to get done.

The data and R code for the analysis reported in this blog post can be found here.

Join the Conversation