This is the first of a two-part blog series on offline open data pilots recently conducted in Indonesia and Kenya. Part one focuses on Indonesia, while the subsequent blog post will describe our findings in Kenya. This series is part of a larger project on the demand for open financial data being conducted by the World Bank Group Open Finances program and World Bank Institute’s Open Contracting Partnership.

Meet Gede Darmawan and Gede Sudiadnya, who live in the village of Desa Ban in Indonesia. These two young men were a part of a story of transformation, one that saw them turn from passive receivers of information to active engagers. It was a remarkable display of the potential power of open financial data.

Gede Darmawan (age 17), Gede Sudiadnya (age 22)

Information has no value if it is not being used.

This idea guided our thinking as we sought to better understand the potential impact of open financial data, particularly in offline environments. While a significant portion of open data activities takes place online, an estimated 65% of people around the world live without internet and lack consistent access to tools, resources, and repositories that live only in the digital realm. Yet, open data has the potential for positive and significant transformational impact in all contexts, not just for communities that are most connected. How would open financial data fare offline? Would the financial and contract information governments and development organizations disclose resonate in communities across the digital divide?

A pilot was designed for and conducted at the kecematan (village) level in Indonesia. We went to the village of Desa Ban to explore these questions and how to realize open data’s potential in environments where interactions between citizens and data primarily take place offline. Desa Ban was selected because of the offline criteria, a variety of local development projects in the area, available information about those projects, and an existing network of contacts at the village level. Within the village of Desa Ban, we worked in two sub-villages: Dusun Ban (population 983) and Dusun Panek (population 737).

Map showing location of Desa Ban

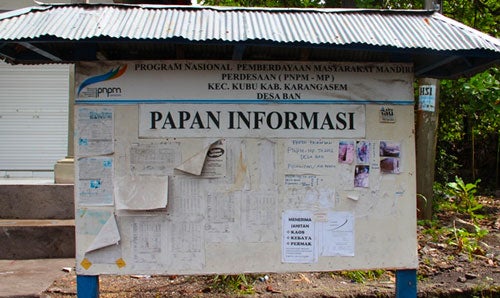

Community information board

Tapping an Existing Community and Structures

Community gathers for meeting

Mobilizing the community in Desa Ban by working with existing groups was essential to the success of the pilot. Thanks to in-country partner Kopernik, we were able to connect with a variety of groups in the village including the Pembinaan Kesejahteraan Keluarga (women’s group), the Sekaa Teruna Teruni (Balinese community youth group), and the banjar (a traditional village men’s group). Over fifty community members gathered on May 26 and June 15 to discuss and share ideas about local development projects taking place in their communities and available information about those projects.

In order to encourage free discussion, groups were split by gender. Facilitators shared information about a road, kindergarten, women’s savings and loans program, water, and irrigation projects. Each group was asked about their preferences around how and what information should be shared. Conducted in Bahasa and Balinese, the group engaged in lively discussions on community priorities, assessed existing information and its potential use (including fields like project description, total budget, community fund allocation, number of beneficiaries), and participated in interactive ranking exercises.

Youth group discusses local projects and financial data

Women’s group shares ideas on potential use of financial data

For the Community, by the Community

For open data to have the greatest impact in offline communities like Desa Ban, it is not enough for the information to just be “out there” and disseminated through usual channels, which are inherently along existing power structures and dynamics. Access to information is just the start. Real impact can only come from more inclusive and interactive methods and means of communication. This can help transform citizens from passive consumers (or non-consumers) of information to active agents of engagement with information in their communities. With that in mind, upon completion of the initial session that helped participants think about the way in which information is currently being shared, we conducted a “community-generated products” exercise. Community members prioritized projects, selected data elements of importance, and further translated the content into posters to help explain the impacts of the projects and relevant data in their communities.

The exercise was quite successful overall, helping identify and understand what about the data was most important to the community members in Desa Ban. The exercise also encouraged the community to think critically about existing data and how it could impact their everyday lives. As publishers of open data and advocates of open government, we were keen for the “theory” of open data to literally “meet the road.” One of the projects selected for visualization was indeed a road project as well.

Community-generated poster creation

With the help of a local artist, the youth group designed and created graphic posters to share the information they had been discussing with other members of the community who had not attended the session. It was very exciting to see village youth develop their ideas and continue to work on their posters well beyond the scheduled time for the session.

Field-testing Community Posters

For participants to truly become actively engaged with the data, it was important that they have an opportunity to share their posters with others in the community. We hoped that participants would be excited about their posters and be able to effectively share their findings with others. But hope is not a strategy, and we needed a live field-test.

After consultation with the community, we decided that the best place to “test” these posters would be the local market, which opens every third day in Desa Ban. As the hub of commerce and activity for many surrounding villages, the market was a natural meeting place. In order to accommodate patrons who travel miles of mountainous terrain to reach the market, it opens very early in the morning around 3:00 AM.

One young man, who had participated in the session named Gede Darmawan, volunteered to bring his poster to the market along with another young man named Gede Sudiadnya from the session. 17 year old Gede Darmawan was not planning to attend the community meeting but had been encouraged by his uncle to do so. By the end of the sessions, he was so enthusiastic about the data and creating his poster that Gede agreed to come to the market the following morning at 3:00 AM to share this information with others members of his community.

Just two days earlier, neither had been exposed to or interacted with the information that they were sharing and discussing in the market. This process of creating materials and sharing them catalyzed a rapid transformation from passive receivers of information to active engagers.

Photo of market sharing

Nano-Survey Update

To complement the information being collected offline, a nano-survey was designed and implemented to capture the demand for open financial data. Nano-survey technology picks up faulty URLs entered by a web user in their browser. When this web traffic is detected, a brief survey is extended. This is exciting for many reasons, including the opportunity to collect information from a random sample (of internet users), the ability to offer country-specific surveys, and the collection of information at a sub-national level in real-time.

While our offline activities were taking place in Desa Ban, a nano-survey was being run in Bahasa across Indonesia. Over 2,000 complete responses to the survey were generated in Indonesia in just 48 hours (a remarkable 12% response rate). In part this can be attributed to the large population of Indonesia, relative high levels of internet penetration, the novelty of the collection mechanism, and translation into local language. A more detailed analysis will follow in a future blog entry and report, but key highlights include: 43% are familiar with the term “open data” (n=1480); 56% want access to public financial information (n=3332); and 30% have used public financial information (n=2523). Like previous sets of information being collected for this project, all data will be shared in open format. This includes “data exhaust” like sub-national location data for all 11,827 unique participants who were extended a survey in Indonesia!

Initial Reflections

There are many encouraging signs that open development data, particularly financial data, is readily consumable and relevant when filtered and translated. A common knock against financial and contract data is that it is too complex or complicated for the average person to understand and process; however, this did not appear to be the case at the village level in Indonesia. When asked to rank types of development information, participants in Desa Ban indicated budget allocation, project objectives, the project selection process, budget monitoring (projected budgets vs expenditures), and procurement and contracting as priorities. The experience also appears to confirm that the value of financial and contract information comes from its ties to specific activities and links to existing community priorities- similar to notions of leveraging community as opposed to building community, it’s not just about creating linkages but discovering and connecting with existing priorities.

The development information that fuels open data platforms has great potential- but it may not be reaching the local level at desired speeds and volumes. Admittedly just one location, but a majority of community members were not aware of the information presented. A cut of data we shared was actually already available on the village information board, though dated and clearly not widely viewed. Even in the Desa Ban sub-village which is located directly next to the village information board, the board went largely unnoticed. Despite these information bottlenecks along existing power structures and channels, there was of course widespread knowledge about the projects themselves well before we conducted our sessions. However, the sessions introduced new information and helped facilitate meaningful feedback and discussion. If we assign value to data by its use and potential for impact, much of open development data’s value lies closer to the ground and will rely on broader and more inclusive dissemination.

Others are also grappling with this dynamic and seeking to bridge the offline-online divide in creative ways. An interesting example of offline feedback being captured and returned online is the “Offline Facebook Wall” in Maputo, Mozambique. Citizens are encouraged to share their thoughts and complaints on a physical wall outside the Verdade Journal. The newspaper takes content back to the Citizen’s Reporter section of their website. Are there other examples we should look more deeply into?

The universal availability, reliability, and affordability of the internet will certainly assist in countering these dynamics to further unlock and realize the potential of open data. At that point, open data has a realistic chance to disrupt existing channels of information dissemination and their underlying power structures. Projects like Google Balloons and O3b (other 3 billion) hoping to expedite the availability of the internet to the emerging world offer hope and a glimpse into a more connected future along with interim offline aspirations like Dropbox’s quest to make every app work offline.

It is critical to consider how to best distribute information to the local level and prioritize the release of information for offline settings, while remaining optimistic for projects listed above to have major breakthroughs. Mobile technology certainly offers a more than potent interim solution- RuaiSMS a project that collects feedback from farmers in rural Indonesia via mobile phones and channels SMS reports to news agencies is an example. There appears to be much room to better link data providers and feedback collectors to increase the value of their respective activities. Integrating open data into traditional sources for information through traditional channels is an ongoing challenge.

We will do some additional processing and analysis of all results. However, it is clear that open financial data is not only relevant but can be readily understood and consumed in offline communities. Open financial data has the potential to break down information silos and empower non-traditional actors. The methodology of encouraging community-generated content and subsequent sharing of that material is also an especially promising development that we hope to test out in more locations and contexts.

Photo of market sharing

We would like to extend a warm thanks to all of our fantastic partners in Indonesia, the community of Desa Ban, the Asia Knowledge & Innovation Lab (AKIL), Program Nasional Pemberdayaan Masyarakat Mandiri (PNPM), the PNPM Support Facility (PSF), RIWI, and our local partner Kopernik.

The next blog entry will cover the offline pilot conducted in Kenya. A more in-depth white paper and multimedia package is also being developed on the entire open financial data demand project.

It’s not too late to participate in the international survey for the open data community (bit.ly/OpenDataDemand) that will complement this research. Please participate and share!

Join the Conversation