Rural economies are in transition as countries seek to boost productivity and growth in the face of rapid out-migration to urban areas, as well as a rise in smallholder farming. Better targeting of initiatives to raise individual productivity and incomes, however, requires accurate estimates of men’s and women’s work (also see Kathleen Beegle’s recent blog on survey measurement of labor).

Rural women, in particular, are often employed in more difficult-to-measure areas, including contributing work in the family farm or enterprise, and seasonal/irregularly-paid labor and farming. Given governments’ efforts to monitor relevant SDG targets relevant to employment, agricultural productivity, and time use (also a focus of global initiatives including 50 x 2030 and the Women’s Work and Employment Partnership), as well as changes in international definitions of employment and work under the 19th International Conference of Labour Statisticians (19th ICLS), improved measurement of rural women’s employment—and constraints to economic opportunity—are key priorities.

I discuss these issues and recommendations for measuring rural women’s employment in a recent paper, using recent LSMS-ISA surveys (Ethiopia, Malawi, Nigeria, and Uganda), as well as pilots conducted by the ILO across 10 countries, between 2015-17, to test how the 19th ICLS guidelines should be implemented in surveys.

Three highlights from the paper:

(1) Importance of recovery questions in capturing contributing family roles

The 19th ICLS narrowed the definition of employment to work for pay/profit—affecting the counting of work that many rural women tend to be engaged in—and recommended in turn that surveys collect complementary data on unpaid work. Figure A shows, using the ILO data, that more detailed framing and recovery questions are needed to prevent underreporting of employment (in this case, in contributing family work, although results were similar for other activities), with the greatest implications for rural women.

Figure A. ILO LFS pilot countries: share of men and women re-classified as employed, through recovery questions on contributing family work

In Figure A above, M1-M5 are the five model questionnaires that the ILO implemented in its pilot study (two implemented in each country). Each model questionnaire was designed to get at the same issues (measuring unpaid and paid work) but with different question order and wording to test out how respondents interpreted and reported outcomes differently, particularly under the 19th ICLS framework. While there are variations across model questionnaires in how well recovery questions perform, it’s clear these questions have particular importance for capturing rural women’s employment.

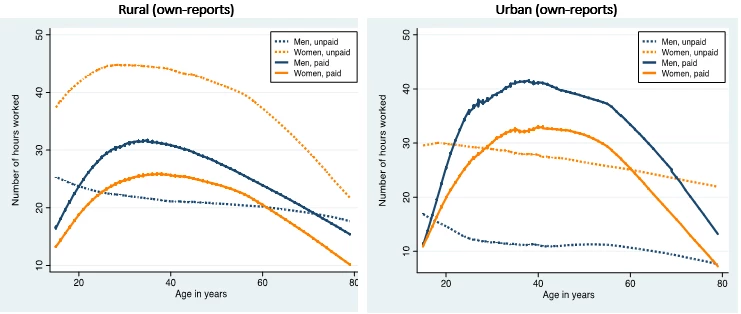

(2) Recognizing and measuring unpaid work burdens

Desire and availability for paid work, and hours worked, are also not independent of unpaid responsibilities—data from the 2013-14 Uganda LSMS-ISA (Figure B) show that rural women have the highest total (paid+unpaid) work burdens as compared to other groups (rural men, urban men/women). Categories of time use could also be refined. Across nine different non-market labor activities, for example, reporting in the Uganda survey was concentrated mainly in two catch-all categories for agriculture and domestic work. Breaking these categories out in more detail—particularly within agriculture—can shed greater insight on how rural programs could be targeted more effectively. Methods for incorporating unpaid work regularly in surveys is an important, ongoing area of research (see a nice discussion by IFPRI as well).

Figure B. Uganda National Panel Survey, 2013-14: hours spent across paid and unpaid activities in the last week

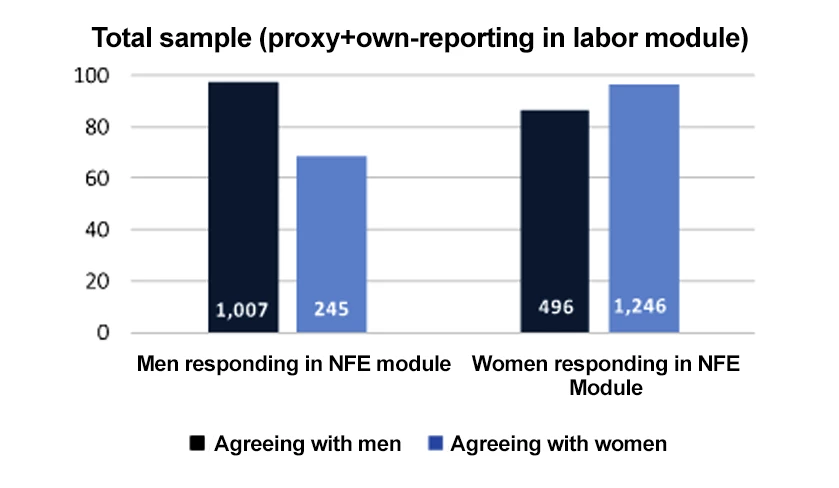

(3) Decision-making over income

Questions on decision-making over earnings and enterprise income can also be helpful in contexts where families pool their income, and particularly where family farms/businesses are common. However, as Figure C shows from the 2016-17 Malawi LSMS-ISA, gendered views of business ownership can affect reporting. Where men were the respondents in the non-farm enterprise module, they agreed with women who reported in the labor module that they ran a business in 68 percent of those cases. Women who were respondents in the enterprise module, however, agreed with men who reported operating a business in the labor module in 86 percent of cases. Ensuring the same respondents across labor/non-farm enterprise modules is important (or that both men and women are asked).

Figure C. Malawi LSMS-ISA, 2016-17: share of respondents in NFE module, that agree with men and women who report in labor module that they run a business

The paper also discusses a number of other key measurement issues, including proxy reporting, informality, and migration, as well as constraints women face in access to markets, skills, better-paying work, and productivity-enhancing technologies and inputs. When collected over time, additional data across these areas can also help provide insights on the dynamics of women’s employment during economic cycles and rural economic shifts, and help in broader economic planning.

Keep an eye out as well for more measurement-related work in this area, including a new paper by Sam Desiere and Valentina Costa on the availability and quality of employment data, and the implications of the 19th ICLS, as well as additional research studies as part of a new IFAD-funded project managed by the World Bank’s Center for Development Data to improve labor data on women and youth.

Join the Conversation