Nobel-laureate economists Esther Duflo and Abhijit Banerjee have recently expressed that, despite decades of intensive research, there is no silver bullet for promoting sustainable and inclusive economic growth. However, the good news is that there are no-regret policies, which include investments in human capital, that are conducive to more prosperous societies.

By improving their skills, health, knowledge, and resilience—their human capital—people can be more productive, flexible, and innovative. Human capital (HC) is a central driver of sustainable growth and poverty reduction. Investments in human capital have become more important as the nature of work has evolved. Yet despite substantial progress, significant gaps in HC investments are leaving the world poorly prepared for what lies ahead.

The World Bank recently completed a comprehensive assessment of the most relevant HC outcomes observed in Liberia. This assessment identified both the leading causes of the outcomes and potential entry points to address the challenges. This was one of the first assessments produced for Sub-Saharan Africa within the context of the World Bank’s Human Capital Project, which is a global effort to accelerate more and better investments in people for greater equity and economic growth. With the COVID-19 pandemic, it is even more important to understand why countries should invest in HC and protect hard-won gains from being eroded.

Liberia presents some of the worst HC outcomes in the world. Liberia’s Human Capital Index (HCI) is 0.32 (of a potential 1.0), which is one of the lowest values worldwide (see Figure 1 below). This means that a child born today in Liberia can be expected to be only 32% as productive when they grow up as they could have been if they had access to the benchmarks of complete education and full health. This low score means that many children in Liberia have their future limited by the circumstances in which they are born, but it also entails difficulties for the economic development of the country. Estimations show that Liberia’s GDP per capita could be almost 3.1 times under the ideal health and education benchmarks. To put things into perspective, this is the equivalent of 2.3 percentage points of additional annual economic growth over the next 50 years, which would be a game-changer for a country that has been struggling to achieve sustained growth.

Figure 1. Liberia’s Human Capital Index is among the lowest in the world.

Let us imagine a cohort of 100 children born in Liberia today. Of those, seven will not survive to the age of 5, and 30 under the age of five will be stunted and, consequently, at risk of cognitive and physical limitations. There is plenty of evidence showing that poor nutrition has effects on learning, in addition to the direct effects on health outcomes. Children who are less affected by stunting in their early years have higher test scores on cognitive assessments and activity level.

Liberian children can expect to complete only around 4.2 years of schooling by the age of 18, which is the second-lowest value in the world. When the expected years of schooling are adjusted by what children actually learn, they are the equivalent of 2.20 years of school education: a learning gap of around 2 years.

The adult survival rate, a proxy for the range of health risks that a child born today would experience as an adult under current conditions, shows that 22 out of every 100 15-year-olds will not survive to the age of 60. It must be mentioned that this indicator has been improving significantly after a drop associated with the second civil war.

While most Liberians over the age of 15 work, the quality of their employment is deficient. Paid work (wage employment) still constitutes only 20% of all employment, with the majority of the employed engaged in either agricultural self-employment (39%) or non-farm self-employment (39%). In addition, 87% of Liberians are in informal employment.

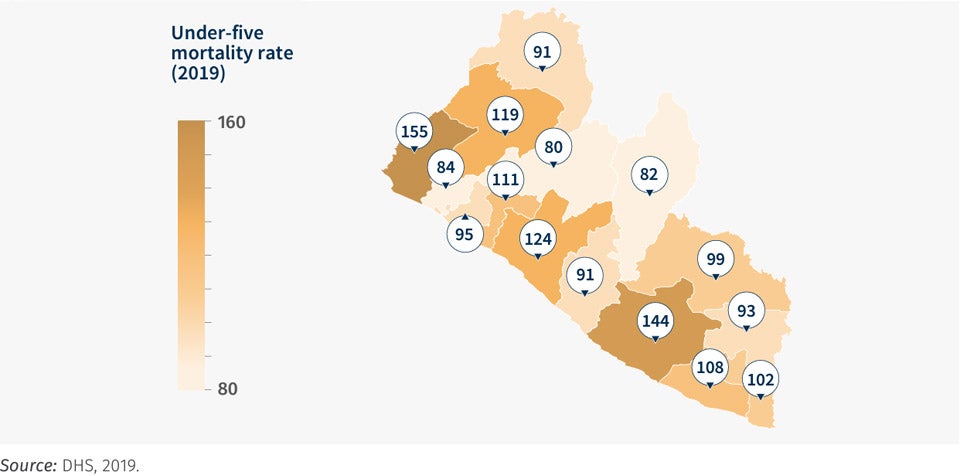

These very low outcomes hide vast inequalities within the country (see Figure 2 below). Our analysis shows that circumstances that are beyond the control of children, such as parental education, parental wealth, location of residence (rural/urban), and county of residence, all appear to account for a significant portion of the observed inequality in access to essential opportunities for Liberian children. Counties such as Montserrado, where the capital Monrovia is located, tend to perform much better than other counties, especially those in rural areas. Households in the lowest quintile of the income and wealth distribution tend to have many more difficulties. Groups such as people with disabilities also have much more trouble accessing services that can help them accumulate and utilize their human capital. Similarly, large gender differences are common across indicators. For example, only 3% of women work in industry, compared to 15% of men.

Figure 2. Liberia’s Human Capital indicators present wide inequalities across regions.

The COVID-19 pandemic will very likely have large impacts on the accumulation and utilization of HC in Liberia. Based on the experience from other countries and other pandemics, at least two effects can be expected. First, most HC outcomes might worsen, given the direct and indirect impact of the pandemic. Second, gaps in the accumulation and utilization of HC might increase, further exacerbating the inequalities the country presents.

The pandemic is expected to have profound adverse effects on education outcomes. Using the simulation method developed by the World Bank, it is possible to estimate the impacts of school closures and the income shock on learning levels. In Liberia, schools were closed for a total of 37 weeks. Under a scenario where schools are closed for seven months, both access to education and learning quality would go down significantly. The estimation shows that the average years of schooling would decline from 4.2 to 3.1 years, and the learning-adjusted years of schooling would decline from 2.2 to 1.5.

Duflo and Banerjee also highlight that, in this world of uncertainty, we need to switch our focus towards people’s well-being. Governments should design policies that could help people explore and exploit their potential while ensuring dignity for everyone. Thus, a focus on HC is needed beyond the economic rationale, which is also very strong. This has been recognized in the Liberia Pro-Poor Agenda for Prosperity and Development 2018-2023, which is the government’s development plan. The strategy is to invest in the early years of life to get the maximum return on human capital and drive the socio-economic development agenda.

Join the Conversation