Regardless of our gender, sooner or later we will reach an age when we will retire from our jobs. When that time comes, pensions will play a critical role as a source of income, poverty prevention and insurance to safeguard long lives. Yet in some countries, financing and eligibility criteria can make pensions less favorable for women.

The Getting a Pension indicator in the Women, Business and the Law 2019: A Decade of Reform report assesses laws affecting women’s pensions by examining retirement ages and pension credits for periods of interrupted employment due to childcare.

Earlier retirement ages can reduce women’s working lives, contribution records and the earnings used to compute pensions. This can adversely impact the gender pension gap. Such differences in legal treatment for men and women particularly matter in publicly managed defined benefit pension systems, where old-age pensions are linked to earnings and contributory histories.

Historically, pension laws tended to set lower retirement ages for women than men. Justifications differ within different geographical contexts, but the more common one is usually around the structure of the family and that women contribute more to traditional family tasks than men. Over the last several decades, governments around the world have reversed this trend by increasing and equalizing retirement ages for men and women due to increased life expectancy, declining fertility rates and fiscal pressures on public finance.

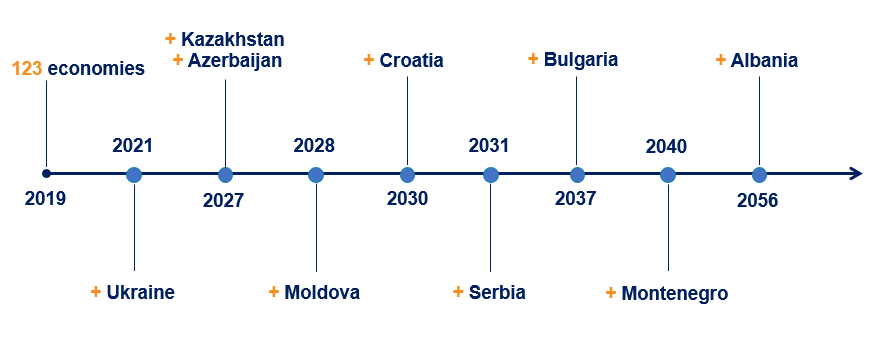

Today, 123 countries worldwide mandate equal retirement ages for men and women for full pension benefits. But this is not the case in 52 countries. More than a third of such cases are in Europe and Central Asia. Nine countries in the region are gradually equalizing retirement ages, allowing women to contribute to their pensions for longer periods. The pace of implementation is fastest in Ukraine, Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, Moldova and Croatia, where retirement ages will fully equalize before or by 2030. Getting to equal retirement will take much longer for women in Serbia, Bulgaria, Montenegro and Albania.

Equalizing Retirement Ages in Europe and Central Asia: The Pace of Implementation

Offsetting mechanisms for periods of interrupted employment due to childcare are also important for women’s pensions. Pension credits are explicit compensating mechanisms in mandatory contributory pension schemes.

Empirical research suggests that a lack of recognition for periods of childcare in pension system design can lead to substantial losses in women’s retirement income. Without pension care credits, women’s replacement rates would decrease by three to seven percentage points on average.

Of the 187 countries examined, 88 provide some form of care credit. OECD high income countries are pioneers in this area. Europe and Central Asia is catching up, with only Azerbaijan, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Georgia, Kosovo and Turkey falling behind. Absence of care credits in East Asia and the Pacific is largely due to the nature of old-income provision structured around individual savings schemes through publicly managed provident funds.

Appropriate policy measures on the labor market side to close gender-related gaps in employment and wages play a crucial role in addressing pension disparities that women face compared to men. In cases, where such measures are not successful, compensating mechanisms on the pension policy side could be another option.

Join the Conversation