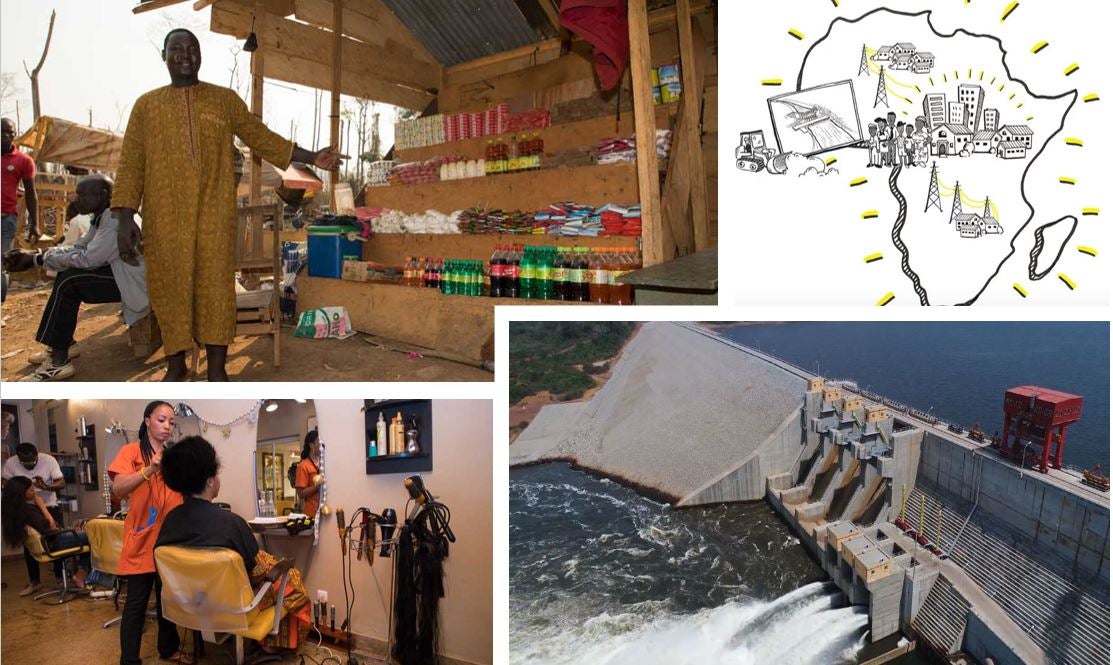

Cameroon has the third largest hydropower development potential in Sub-Saharan Africa—estimated at over 12,000 megawatts (MW). Yet, despite these resources, only half the population has access to electricity. Moreover, the average retail price is more than €0.12/kilowatt hour (kWh)—higher than many U.S. consumers pay.

Deploying hydropower resources is key to lowering the cost of electricity and ensuring a competitive economy. The 420 MW Nachtigal project goes far to achieve this, while boasting limited environmental and social impacts. The project cost is estimated at €1.2 billion with a five-year construction period. Once constructed, Nachtigal will provide clean, affordable, base load power for €0.6/kWh.

One of Nachtigal’s key innovations is the mobilization of an unprecedented 21-year local currency facility whereby five local and regional commercial banks are providing debt financing of €171 million— about one-fifth of the total project debt.

In theory, local currency financing can reduce currency mismatch risks of infrastructure projects. It can also reduce foreign exchange exposure for countries and help develop the local market, building local banks’ capacity. But in practice few large projects in Sub-Saharan Africa benefit from domestic finance. In fact, since 2014, only two of 55 reported infrastructure projects in the region (with the exception of South Africa) have closed with finance from local banks or investment funds. There are several reasons for this; let’s explore a few:

- Most infrastructure financing needs are in hard currency. In much of Sub-Saharan Africa, it’s not efficient to swap local currency to hard currencies. This limits the usefulness of local currency financing.

- Local banks often lack the expertise to deliver complex project financings. In addition, balance sheet or regulatory limits often preclude local banks from providing debt with more than a 5–7 year tenor.

- Local currency volatility and convertibility limit the appetite of project developers to take local currency risk; often they demand government take it instead. This is accomplished through a euro-US dollar indexed tariff structure. When the government takes on currency risk developers are not incentivized to seek local currency financing.

First, interests were aligned between the developers, lenders, government, and the guarantor (the World Bank). The government’s aim was twofold: maximize the local currency component to reduce foreign currency exposure and develop local lending capacity for long-term project finance. For the developers and lenders, they accepted about 20 percent of the Power Purchase Agreement tariff in local currency without indexation to foreign currencies. This helps finance local content, which is significant for the project. Local currency financing provided a natural hedge against the portion of tariff payable in local currency. For the World Bank, we recognized the development impact of mobilizing private sector financing while helping local banks.

The limited underwriting capacity of local banks was partly mitigated by the extensive involvement of the World Bank Group. The International Finance Corporation (IFC), as the structuring bank, led the technical, financial, and environmental/social due diligence while coordinating different development finance and commercial banks. Local banks benefited from this comprehensive process and deal structuring led by a global finance institution.

Another element was the World Bank’s deployment of a loan guarantee to mitigate government and regulatory risks to enable a 21-year loan from local banks. The World Bank and the lenders developed a structure giving local banks the choice to sell the loan back to the government at the end of years 7 and 14 if the local bank cannot be replaced. This effectively granted the local banks two put options to transfer the loan off of their balance sheets under certain pricing conditions. The government’s commitment to purchase the loan at years 7 and 14 was further backstopped by the IBRD guarantee. This way, the local banks gained the flexibility to extend the tenor and achieve the amortization profile while complying with regulations.

Lastly, the local currency (CFA franc) has been stable with a reasonable base rate and its convertibility is generally known. Indeed, Cameroon is a member country of the Central African Economic and Monetary Community. The CFA franc has a fixed exchange rate with the Euro and its convertibility is guaranteed by the French treasury. These features make it a stable currency even when the countries that use it face political and economic uncertainties.

Frankly, local financing for Nachtigal was not expected at the beginning. It came as a result of all parties’ open-mindedness and determination. The World Bank played an honest broker role to align interests and design a win-win structure. The structure and the *tenor of the loan were truly unprecedented. But, what’s more, it drove down the annual cash flow requirement for debt service due to tenor extension, resulting in a lower tariff. The structure further allowed a significant portion of the tariff to be denominated and paid in CFA francs, reducing foreign exchange risk to the country.

While it takes time to develop long-term infrastructure financing capacity and markets in Sub-Saharan Africa, Nachtigal demonstrated that local currency financing is possible, today—if sponsors, lenders, and the development finance community are innovative and committed to finding solutions. Certainly, from the World Bank’s perspective, we look forward to replicating this solution elsewhere.

* In 2014, Kribi Power Project in Cameroon reached financial close. The financing package included a $60 million-equivalent local currency tranche. The Kribi transaction had a similar debt structure, providing a good precedent for the Nachtigal project

Related

Maximizing concessional resources with guarantees—a perspective on sovereigns and sub-nationals

Scaling up World Bank guarantees to move the needle on infrastructure finance

Cameroon’s Nachtigal Taps New Possibilities for Clean Power

How World Bank Group Collaboration Is Bringing Power to Cameroon

Join the Conversation