Infrastructure technology. Photo credit: Geralt, Pixabay

Infrastructure technology. Photo credit: Geralt, Pixabay

No one understands the financial risks of climate change better than insurance companies. As I sit down to write this blog on what we need to accelerate and fund the convergence of infrastructure and technology, Hurricane Dorian is parked over the Bahamas wreaking unimaginable havoc. It is tragic — and yet familiar to the masses not directly sitting in the storm’s path.

Another year. Another storm. A predictable news cycle.

In 2017, when Hurricane Maria was carving a deadly path through the Caribbean, I was involved (through the Insurance Development Forum) with a working group led by the United Nations Development Program to explore the feasibility of creating an “Infrastructure for Development Fund.” The aim was to create a traditional debt-focused infrastructure fund led by insurance investors that would target transactions that improve the resilience of infrastructure — particularly in developing countries.

The subject of resilience was highly relevant at the time as the hurricane season that year was one of the worst in living memory. In addition to Maria, hurricanes Harvey and Irma also racked up billions of dollars of damage across the Caribbean as well as the Atlantic, and Gulf of Mexico coasts. While costs in the United States related to these storms are fairly well documented, the lack of public and private insurance for infrastructure assets — together with a lack of official statistics — tends to downplay disasters’ significance and ‘uncounted’ impact in developing countries.

Insurance companies understand catastrophe risk, and the working group was guided by a few simple principles that underpinned its belief that the industry is the natural partner for long-term infrastructure development. First, quality infrastructure is essential for establishing quality insurance markets. Improving infrastructure to address catastrophe risk makes communities more resilient and lowers the industry’s exposure to future claims. It also lowers customers’ premiums, making insurance more affordable. Selling more insurance premiums in developing-country markets raises more capital, which can then be invested in more infrastructure. On PowerPoint, this is a virtuous circle. In reality, it’s disconnected and quite challenging to bring together.

So what does any of this have to do with the application of technology to physical infrastructure? More than you might think.

In addition to driving efficiency and profitability through greater connectivity, I believe that technology and design are the only meaningful ways to boost infrastructure resilience and divert catastrophic climate change. But like the virtuous circle of insurance and infrastructure investment, it simply will not happen organically. It must be driven by policy.

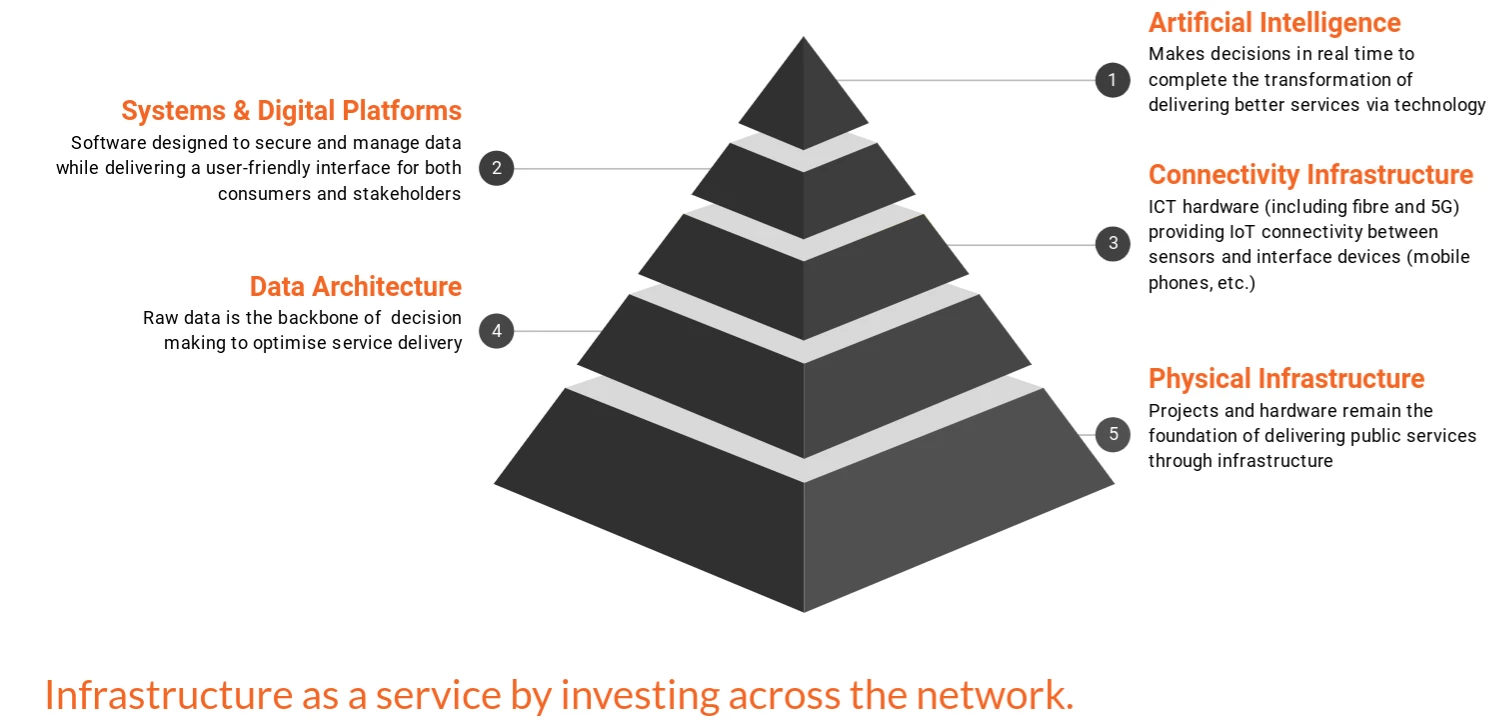

Infrastructure + Technology (or InfraTech) is a system that can be imagined through a pyramid. The bottom layer is physical infrastructure — still the foundation of delivering public services. Above physical infrastructure is the data architecture to support decision making and optimize service delivery. The data architecture establishes what is needed in the next layer up — connectivity infrastructure (including broadband and, soon, 5G). This layer utilizes sensors, QR codes, and communications technology to feed information up into the digital platform layer with specialized software designed to secure and manage data. These content management systems can also be used to provide user-friendly interfaces for consumers and stakeholders — creating more opportunities for people to engage productively with infrastructure. Finally, at the top of the pyramid is artificial intelligence. AI would utilize the speed of computing to enable decisions in real time. This would close the system and complete the digital transformation of delivering better public services via Infrastructure + Technology.

What might that look like in real life?

Energy transition is at the heart of many conversations on sustainability, and islands — not unlike those hurricane-fatigued nation states in the Caribbean — are perfect test beds. Islands typically rely on dirty and expensive diesel generation distributed through old, poorly-maintained overhead power grids — a recipe for disaster when a storm like Maria or Dorian blows in.

There’s an ambitious road map utilizing InfraTech to create a new low-carbon system of energy services — including heating, cooling, motion, light, and sound — designed with resilience at its core. The system deploys distributed renewable energy generation combined with electrolyzers for energy storage, a hydrogen grid for distribution, and hydrogen or electric powered vehicles for transportation. The whole system is optimized using digital platforms — like Power Ledger’s energy trading software — to intelligently transact efficiency.

The upfront cost would be significant, but the long-term benefits of building such a resilient energy system could be managed and save governments billions of dollars in disaster recovery funding down the road.

These technologies exist, and the start-up culture around them is palpable. Investors backing these companies are reimagining the way the world works, which is never easy. I recently spoke to my friend Max Carcas at Caelulum Limited about the challenge of deploying these InfraTech ideas in real environments. Max works with island communities in the United Kingdom to clean up their energy supply and distribution. One unexpected challenge is overcoming entrenched interests:

“We think renewables would be kind of a no-brainer compared to diesel generation. But of course, quite often what happens is the incumbent generator makes a lot of money from the diesel generation, even though it's very expensive. And they pay the government quite a lot of taxes through that. So the government is not interested in new entrants coming in or consumers depriving them of that revenue base. They may of course not say that openly, but these drivers can be against you if you're not careful.”

Which brings me back to policy. Remember the old adage encouraging people to “be the change they wish to see in the world”? Well, it starts with governments recognizing the true cost of entrenched infrastructure. The market will competitively deliver components within the InfraTech pyramid, but it will not deliver the system. Governments are responsible for aligning the system — either through regulation or management. That requires political commitment, direct investment and ... insurance.

The Infrastructure + Technology pyramid is essentially an insurance policy to protect our future . As a clean industrial strategy, it can deliver real social impact and economic growth while ensuring public services are resilient, sustainable, and commercially-viable well into the future.

Disclaimer: The content of this blog does not necessarily reflect the views of the World Bank Group, its Board of Executive Directors, staff or the governments it represents. The World Bank Group does not guarantee the accuracy of the data, findings, or analysis in this post.

Relates Posts

Factoring climate risk into infrastructure investment

What’s next for ESG and investment decisions?

Regenerative PPPs (R+PPP): Designing PPPs that keep delivering

Future-Proofing Resilient PPPs

How to protect infrastructure from a changing climate

10 candid career questions with PPP professionals – John Kjorstad

Join the Conversation