with research contributions from Zichao Wei

While sitting in the World Bank gives us a bird’s-eye view of emerging markets and developing economies (EMDEs), it doesn’t offer the up-close-and-personal perspective that investors demand in order to answer these questions in a succinct way. Not that there’s any shortage of synoptic responses. Any number of “market gurus” can assess projects in a second, gathering all the low hanging fruits which are out there in EMDEs. If there is a private deal to be made, then the deal is already done.

Assessing investment possibilities becomes complicated where there is a third party involved. I live and breathe this challenge because I work in the world of public-private partnerships (PPPs) – developing infrastructure finance – where the deal is tough to come by. In the PPP universe, the government is not only the grantor but also the procurer of goods and services, policy maker, regulator, supplier, and buyer or off -taker of the outputs. And this is a universe where the 10,000-foot view of infrastructure in emerging markets is a useful perspective from which to examine the global infrastructure investment landscape.

Getting the lay of the land

Before looking at the global infrastructure investment landscape, it is important to know which regions have the greatest needs. A recent World Bank study[1] shows South Asia ranking at the top (see the graph below) in terms of both annual infrastructure investment requirement as percentage of GDP (15%) and absolute terms of investment amount ($300 billion). What does this number mean? In order to keep up with the regional predicted GDP growth rate of 6%, the South Asia region countries need to invest nearly 15% of their GDP in new infrastructure and to maintain existing infrastructure.

Notwithstanding these findings, an examination of the Private Participation in Infrastructure (PPI) database shows that the top destinations for private sector investment continue to be Brazil, China, India, Mexico, and Turkey. These five countries accounted for 73% of investments and 63% of all projects in 2014.

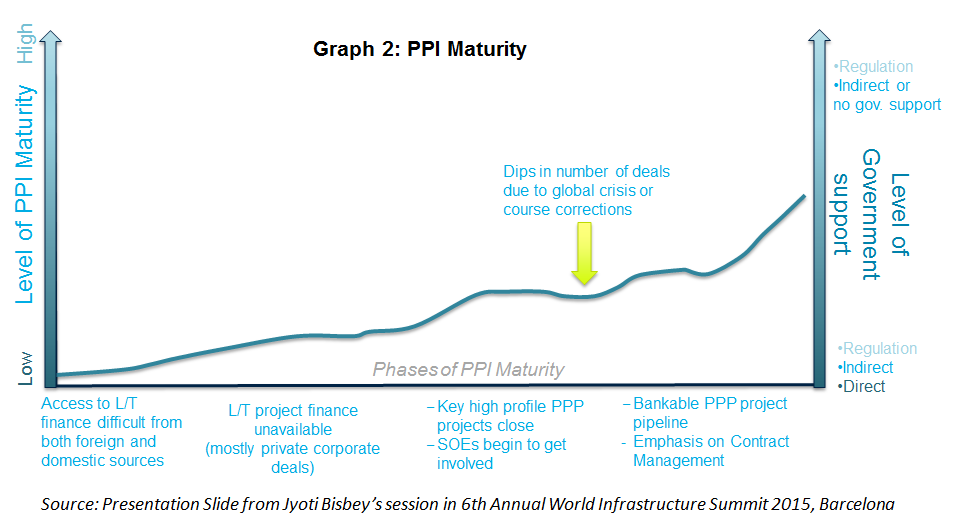

So what happens to the rest of EMDEs? These overlooked countries, working toward PPI maturity, truly fit the definition of “emerging economies.” I’ve broken down this concept so we can quantify these nations’ potential for private investment in infrastructure, and the graph below depicts how a country can be considered an investment destination.

I define PPI maturity to be a function of understanding, willingness, and commitment toward PPI under the current circumstances. Maturity could range from high to low (Y axis). PPI maturity looks specifically at private sector participation in public infrastructure and will require different levels of government support depending on country’s capacity (Z axis). PPI maturity could be different at a given time and for a given country.

There are further considerations. On the graph, the X axis shows areas or phases which, in my experience, weigh heavily on a project’s chances of success. These include:

- Whether the project will even have access to long term financing from either domestic or foreign source?

- If there is availability of this long term financing to public infrastructure?

- Have any of the high priority projects closed, and at the same time, are state-owned enterprises beginning to see the value of PPI? and

- Are sub-nationals entering the PPI market? (For those that experienced the first generation of PPPs, are they bearing lessons and putting more emphasis on contract management?)

Charting a course

This last point – whether a country continues to learn and improve – is key. There are many countries that are making the effort to be PPI mature and market ready. Some are clarifying their PPP legal framework, some are professionalizing their financial and local capital markets, and some are already launching pilot projects. Several countries have progressed to a second generation of PPPs, building on the lessons from the first wave or going back to the drawing board.

There’s no right answer to the two questions that keep coming my way, and which are certainly directed at countless other infrastructure finance professionals around the world. Not only is there no right way, but if there’s an approach that works one day, the next day will be different. Successful PPP deal-making will keep changing according to the circumstance, government support, and level of PPI maturity. Charting these elements, as in the graph above, is the first step toward mapping out a future for infrastructure finance possibilities in EMDEs.

Join the Conversation