Photo: VahanN / Shutterstock.com

Downtown Yerevan. Gusty winds, frosty air. Inside a hotel in the town square, cocktails and canapés, speeches and signatures. On this evening in November 2016, representatives of the State Committee for Water Economy (the Armenian water authority) and Veolia (a large international water operator) gathered to celebrate the signing of a new partnership: a 15-year national lease to provide water and wastewater services for the whole country. The lease began in January 2017, thus marking the start of a “second generation” of water PPPs in Armenia. Solid gains had already been made under the “first generation” between 2000 and 2016. At this crucial juncture, a World Bank study reviewed Armenia’s experience so far and analyzed the way forward under the new national lease.

The government ’ s evidence-based “ leap of faith ”

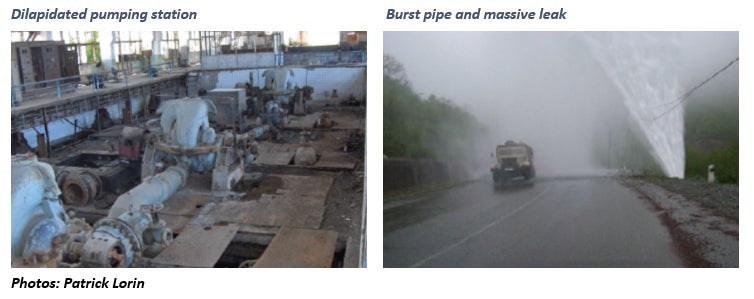

When Armenia gained independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, most of its water and wastewater facilities were over 30 years old and badly in need of maintenance and upgrading. The pictures below illustrate the state of the infrastructure in the early 2000s. Services were scant, with most areas in Armenia receiving less than six hours of water supply a day.

Facing this crisis, the government made a radical decision. After a World Bank-financed trip to study private sector participation in the water sectors of Hungary, France and Poland, a high-level Armenian delegation was inspired to pilot the approach back home. Subsequently, the government signed a management contract with a private operator for the Yerevan Water and Sewerage Company (2000–06). It was followed by a lease contract in Yerevan (2006–16), a management contract in secondary towns and cities under the Armenian Water and Sewerage Company or AWSC (2004–16), and a joint management contract of three regional utilities (2009–16). In all, this “first generation” of PPPs lasted 16 years.

Highs and lows, but strikingly good results overall

Private sector operation in Yerevan, AWSC and the three regional utilities (Table 1) brought clear improvements: the hours of water supply increased dramatically, reaching nearly 24/7 in Yerevan; water assets were constructed or rehabilitated; customer service was professionalized; and labor productivity improved (meaning fewer staff were needed to provide services, a sign of efficiency). Remarkably, even though all service areas under private operation saw steep tariff increases (even 42% in the poorer, regional service areas), for the most part, the public supported the PPPs and was willing to pay for improved water services. In a 2011 survey, only 30% of residents in Yerevan wanted to revert to public management. In the AWSC’s area, that number was 33%, suggesting that support for PPPs was widespread.

Despite the mostly positive results, little progress was made to reduce water losses, which grew because of increasing the water supply. The availability of plentiful and cheap water resources made the need to reduce leakage less compelling than in other countries. The government was also constrained by a shortage of funds to rehabilitate dilapidated networks.

The PPPs also failed to improve the financial performance of water utilities outside of Yerevan. While water services in Yerevan, under a lease contract from 2006 to 2016, became financially self-sufficient by 2011, tariffs were still below full cost recovery in the rest of the country served by management contracts. It should be noted, however, that weak cost recovery in Armenia during this time mainly reflects political decisions linked to water tariff levels rather than an inherent weakness of the PPP approach.

As the various PPP projects launched in 2000 came to an end in 2016, the government decided to continue its partnership with the private sector. The government also recognized that there were several areas not fully addressed under the first generation of PPPs—such as the reduction of water losses, expansion of wastewater treatment, financial self-sufficiency of water utilities, and service-provision to 579 unconnected communities in rural areas. Consequently, the government turned to a national lease contract with one operator. The lease has been underway since January 2017 and will be in effect for 15 years. It places greater emphasis on non-revenue water reduction, developing wastewater treatment infrastructure, and ensuring full operations and maintenance cost recovery from tariffs.

The Armenian experience spotlights several key lessons and good practices, including:

- The importance of a dedicated government agency to serve as the focal point for the private operator.

- Taking a sequenced approach with increasing risk transfer to the private sector over time.

- Implementing the PPP agenda without waiting for the full suite of legislation and reforms to be in place.

- Putting the private operator in charge of capital expenditure, while the public sector monitors and finances the works.

- Ensuring adequate tariff increases to complement cost reduction and efficiency gains in order to optimize financial results.

- Securing continuous support from donors for capital expenditure and technical assistance, particularly in the early stages of PPPs.

For more information on Armenia’s experience with Water PPPs, see this report produced by the World Bank’s Water Global Practice and funded by the Public-Private Infrastructure Advisory Facility (PPIAF).

Related links:

5 trends in public-private partnerships in water supply and sanitation

Water in Armenia - from Shortage to Abundance

In Armenia: Clean, Constant Water in Yerevan

Armenia: Water

Join the Conversation