Source: Branko Milanovic

If you thought the wealth gap was vast between the miser Ebenezer Scrooge and the oppressed Bob Cratchit in “A Christmas Carol,” then lend a Christmastime thought for the desperate Dickensian divide that’s now afflicting the global economy.

The biggest economic-policy issue of 2014 has certainly been the outpouring of alarm about the chronically intensifying divide between wealth and poverty – an uproar that has had a transformational effect on the worldwide debate on economic policy. As a seminar at the Center for Global Development recently discussed, the precise statistics on inequality (and the perception of inequality) are subtle, with many nuances of measurement (whether data should be derived, for example, from tax-return filings or from household surveys). Yet this year’s irrefutable interpretation among economists and business leaders has been driven by a landmark of economic scholarship: the bombshell book “Capital in the Twenty-First Century” by Thomas Piketty. “Capital” has forced economists, policymakers and scholars to reconsider the inexorable trends that are driving the modern-day economy toward an ever-more-intense concentration of capital in fewer and fewer hands.

No wonder Piketty’s “Capital” was hailed as the Financial Times/McKinsey “Business Book of the Year.” Piketty’s analysis has fundamentally changed the parameters of the public-policy debate, and many of its ideas challenge conventional economic theory.

To explore the implications of the alarming trends in income and wealth inequality, there’s no analyst more insightful than Branko Milanovic, the former World Bank economist who is now a scholar at the LIS Center (working on the authoritative Luxembourg Income Study) at the City University of New York. Milanovic has justly won acclaim for his work, “The Haves and the Have-Nots,” which pioneered the territory now being explored by Piketty.

Confirming the trends that Piketty identified in “Capital” – and taking those insights one significant step further, to measure the wealth gaps both within countries and between countries – Milanovic recently led a compelling CGD seminar on “Winners and Losers of Globalization: Political Implications of Inequality.”

The seminar’s sobering conclusion: If you think the wealth-and-incomes gap is painful now, just wait a decade or two. If allowed to go unattended, the widening economic divide will soon become a dangerous social chasm. That data-driven projection is leading many analysts to dread that inequality (whether between countries or within the same country) threatens topose a stark challenge to social stability, and even to the survival of democracy.

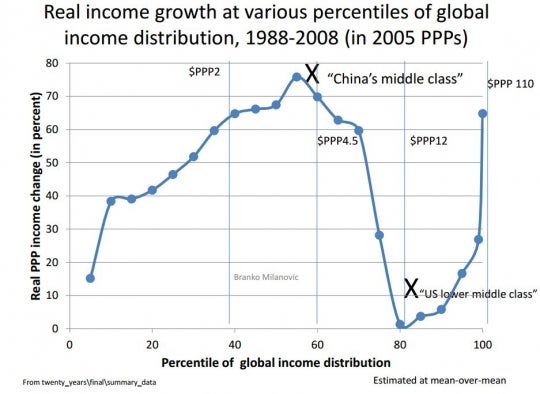

The breakthtaking “a-ha!” moment of Milanovic’s CGD presentation was the chart (see the illustration, above) – praised as "the Chart of the Century" by seminar chairman Michael Clemens of CGD and discussant Laurence Chandy of the Brookings Institution – that plotted-out the pattern of how globalization has exerted relentless downward pressure on the incomes of the global upper-middle class, which roughly corresponds to the Western lower-middle class.

Globalization has helped promote the prosperity of skilled workers in developing nations, Milanovic explained, with the dramatic surge of China’s economy being the greatest driver of global “convergence.” Yet globalization has had an undeniable downward effect on the wealth and incomes of low- and medium-skilled workers in developed, industrialized nations. That certainly helps explain the angry mood among voters in Western Europe and North America, whose overall incomes and wealth have been stagnating for perhaps 40 years.

At the same time – reinforcing the significance of Piketty’s iconic formula that r>g (that the returns on capital are destined to be greater than overall economic growth) – a vast proportion of the world’s wealth has been concentrated in just the very top echelons of society. Milanovic’s meticulous data (see the illustration, below) confirm the extreme concentration of global absolute gains in income, from 1988 to 2008, in the top 5 percent of the world’s income distribution. Rigorous empirical evidence from multiple sources indeed confirms that most of the global gains in wealth have accrued to the already-vastly-wealthy top One Percent. The data on increasing socioeconomic stratification are, by now, so well-established that only the predictable claque of free-market absolutists and dogmatic denierscling (with increasing desperation) to the notion that the inequality gap is merely a myth.

Source: Branko Milanovic

Reinforcing Milanovic’s analysis, yet another well-documented study – this time, by the OECD– asserted this month that economic inequality is intensifying within the world’s developed nations. That within-country trend accompanies the yawning inequality gap between developed and developing economies. The OECD thus joined the chorus that includes the World Bank Group, the International Monetary Fund, the United Nations’ Department of Economic and Social Affairs and the U.S. Federal Reserve System in sounding the alarm about the way that income and wealth disparities are becoming socially explosive. Even on Wall Street, many pragmatists are warning with increasing urgency that “too much inequality can undermine growth.”

Economic inequality – both the perception and the reality of the egregious global gap – has surely been the key economic theme of 2014, and Milanovic’s CGD presentation capped the year with what the seminar-goers recognized as authoritative data distilled into “the Chart of the Century.” Milanovic thus echoed warnings by National Economic Council chairman Jason Furman and Canadian Member of Parliament Chrystia Freeland (both of whom have led recent World Bank seminars), who cautioned Washington policymakers about the potential dangers of runaway inequality.

Energized by Milanovic’s latest calculations and analysis, scholars and development practitioners at the World Bank Group and beyond should approach 2015 with a renewed commitment to building prosperity that is truly shared – and that avoids the potential social explosion that might await many economies if runaway inequality is allowed to continue unchecked.

Join the Conversation