On a recent trip to Ireland, stories about the impact of the continuing economic crisis were abundant. Newspapers ran stories about the substantial loss of wealth and purchasing power, such as the increase in 'negative equity' as the value of homes owned by the middle class fell significantly below their mortgages. Cab drivers explained how jobs had been shed throughout the economy, and bemoaned the resulting rise in the number of drivers and increased competition for fares. The reality of the recession and fiscal collapse following the banking crisis of late 2008 was clear.

However, anecdotal evidence about a different aspect of Irish finance – foreign direct investment – suggested a more positive story. I walked through one neighborhood in Dublin that houses the European headquarters of Google, Facebook, and LinkedIn. The latter two were established after the onset of the economic crisis, and Google is in the process of expanding its presence in Dublin. Lawyers at large corporate law firms were excited to discuss FDI, citing it as a key driver of Ireland’s future growth. One firm even maintains a FDI index that highlights large inflows and the positive perception of Ireland as a destination for US investment.

Might FDI in Ireland be the best indicator to consider the strength of the economic fundamentals that enable long-term growth? Ireland has historically benefitted from large inflows of FDI relative to its size. And despite the recent economic crisis, these inflows have largely continued.

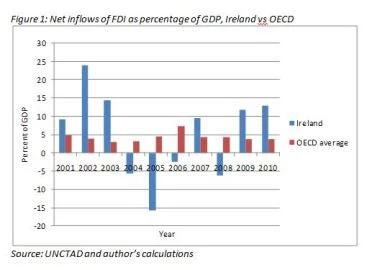

Over the past 10 years, inflows of FDI into Ireland tend to be substantially higher as a percentage of GDP than inflows into other OECD economies (see Figure 1). In 2009 and 2010, the two years immediately following the banking collapse, Ireland attracted three to four times more FDI proportionately than other OECD economies. These inflows were not just large in relative terms – they were equivalent to 11.7% of GDP in 2009 and 12.9% in 2010. The negative inflows in 2005 and 2008 do indicate that more money was disinvested out of Ireland than newly invested in the economy those years. However, such outflows are mostly loans or dividend payments from foreign-owned firms in Ireland to their affiliates abroad, at least some of which were likely caused by a 2004 change in the US tax rate on foreign profits.

Figure 1: Net inflows of FDI as percentage of GDP, Ireland vs OECD

Source: UNCTAD and author’s calculations

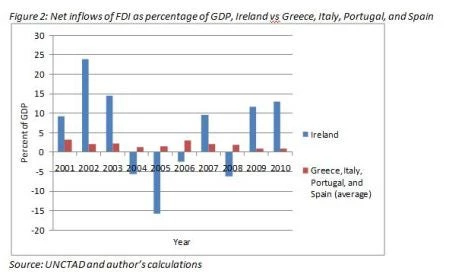

This same pattern of relatively large inward FDI is even more pronounced when comparing Ireland to other European economies that have also experienced recent asset price crashes or fiscal crises. In years when net inflows are positive, Ireland has attracted five to ten times more FDI as a percentage of GDP than Greece, Italy, Portugal, and Spain on average, as seen in Figure 2:

Figure 2: Net inflows of FDI as percentage of GDP, Ireland vs Greece, Italy, Portugal, and Spain

Source: UNCTAD and author’s calculations

What aspects of the Irish economy attract these large FDI inflows? Ireland’s corporate tax rate, one of the lowest in the developed world, is certainly a factor. France and Germany are even pushing forthe rate to be raised as part of EU fiscal coordination efforts. Much investment is in the technology or service sectors, which likely reflects Ireland’s highly skilled workforce (as well as tax policy designed to attract intellectual property development). And the English language capabilities and access to the EU market are very attractive to US investors.

Regulatory issues also matter. The Irish law firm’s survey cited above indicates that US investors view the regulatory environment in Ireland far more positively than in the rest of Western Europe, a perception supported by indicators developed by the World Bank Group's Global Analysis and Indicators department. Measures of select aspects of FDI regulations indicated in 2010 that it takes only 5 procedures and 14 days to start a foreign business in Ireland, one of the simplest processes amongst OECD economies. The Irish economy is also fully open to foreign equity ownership across a wide range of sectors. Ireland is ranked 10th in the world for ease of doing business for locally owned firms by Doing Business 2012 supporting the overall perspective that the Irish government maintains a favorable environment for local and foreign business in its economy.

The government continues to make regulatory reforms to compete for and attract FDI: in 2010 it reformed its commercial arbitration regime to adopt the UNCITRAL Model Law. Should further efforts to keep Ireland a top destination for FDI be a key economic policy goal? There is some debate as to how much potential FDI has to enable additional economic growth. And a stronger investment climate will not likely solve the immediate problem of households with negative home equity. But attracting more FDI may be a crucial aspect of overcoming the crisis, creating jobs, and achieving economic growth in the long run.

Join the Conversation