As COVID-19 sweeps the world and disrupts the way we interact and conduct business, innovative technologies can help by providing solutions to maintain social distancing, ensure business continuity, strengthen health-care outcomes, and prevent service disruptions. By reducing the dependence on physical financial interactions and the need for cash, fintech can facilitate government responses and enable secure ways for governments and providers to reach vulnerable populations quickly and efficiently.

But policymakers worldwide have long been finding themselves in a regulatory dilemma when trying to achieve the right balance between enabling fintech and safeguarding the financial system. The spread of COVID-19 heightens the need to find a balance that can enable innovation and efficiency, and reduce financial and economic vulnerabilities while keeping risks in check.

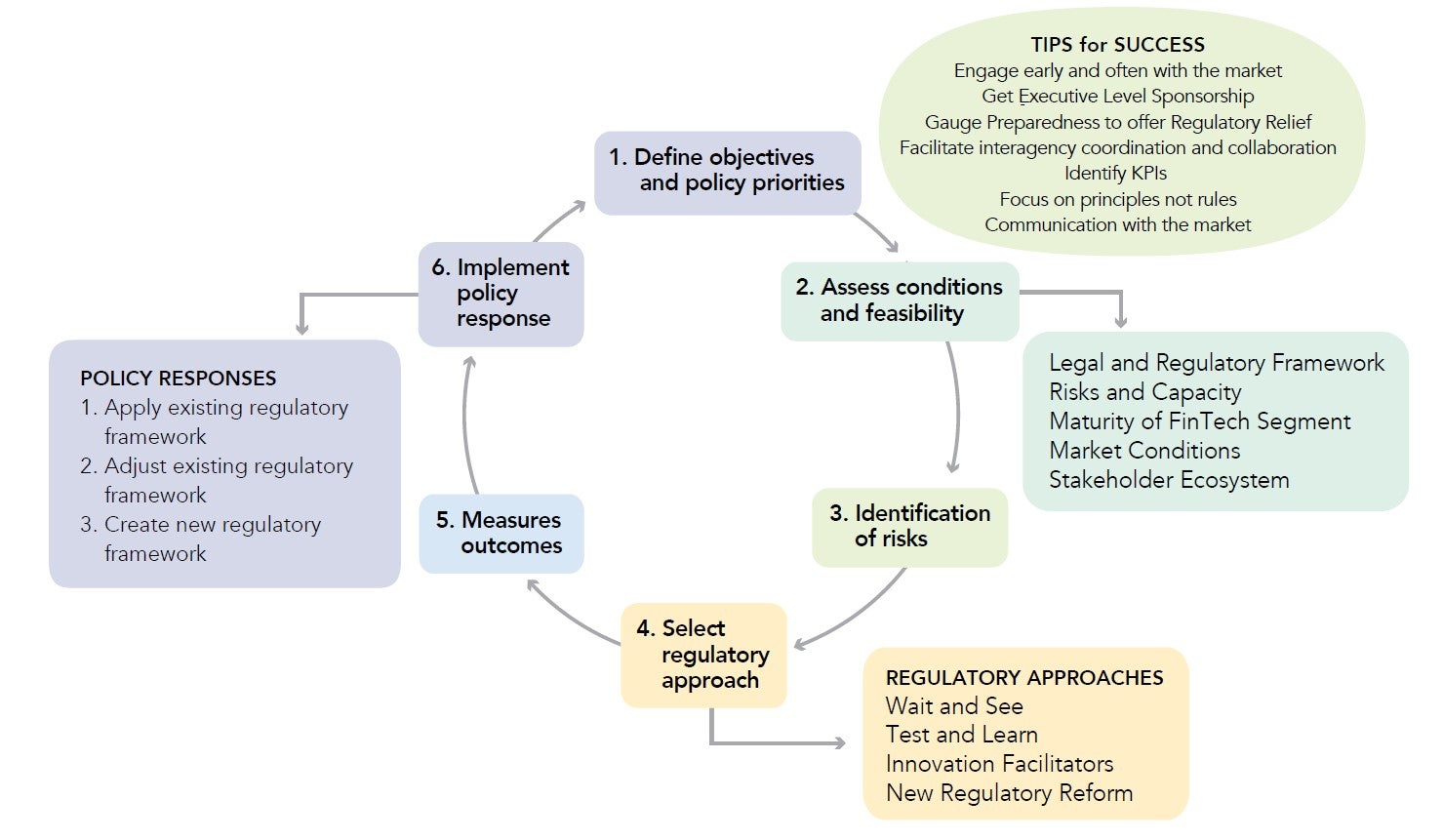

There is not a one-size-fits-all approach to address the challenge, and what works for one country may not work for another. But our recent report, How Regulators Respond to Fintech: Evaluating the Different Approaches beyond Sandboxes, can inform and guide stakeholders around emerging regulatory approaches and key considerations, and help policymakers evaluate the right regulatory approach and ultimate policy response for their own contexts.

What are the existing regulatory approaches?

Regulatory approaches aimed at promoting innovation and experimentation—described in brief below and more fully in the paper—support and guide policymakers toward the most useful policy response:

These approaches can be applied either in combination or solely, and more than one initiative can be adopted in tandem to maximize its impact and efficiency. In the report, they were classified into four categories:

- “Wait and See”

Regulators observe and monitor trends of innovation from afar before intervening where and when necessary. This approach has commonly emerged when there is regulatory ambiguity on whether an activity falls under the scope of a particular institution, or when there is a need to further build regulator capacity and understanding prior to issuing a response. Many countries have applied this approach, for instance, in the treatment of cloud computing or developments in distributed ledger technology.

- “Test and Learn”

The creation of a custom framework for each individual business case, allowing it to function in a live environment. The extensiveness of supervision and oversight, as well as the safeguard measures put in place, have varied across areas. The most well-know and successful example is the treatment of mobile phone-based money transfer service in Kenya leading to the creation of M-Pesa.

- Innovation Facilitators

A point of contact or a structured framework environment created to promote innovation and experimentation. This approach can be divided into three sub-categories:

- Innovation Hubs: Most often a central point of contact to streamline queries and provide support, advice, and guidance to help firms navigate the regulatory, supervisory, policy, or legal environment. However, the form and format vary depending on the appetite of the regulator. For example, Malaysia (Digital Finance Innovation Hub) and Thailand (OJK Infinity) have set up innovation hubs with other players that go beyond the financial sector. In addition to providing regulatory clarity, they enable service providers, including financial institutions, fintech start-ups, and academics to collaborate.

- Regulatory Sandboxes: A controlled, time-bound live testing environment that allows innovators to test new products, services, or business models on a small scale, in a controlled manner, subject to regulatory discretion and proportionality. There are nearly 80 regulatory sandboxes announced worldwide with some focusing specifically on financial inclusion such as those in Sierra Leone and India. An upcoming paper on sandboxes will outline lessons learned from their operation in emerging markets and developing economies.

- Regulatory Accelerators: Enables partnership arrangements between fintech firms and policymakers to innovate on shared technologies, most commonly to solve pre-defined use cases. In the Philippines, the Bangko Sentral Ng Philipinas (BSP) developed a RegTech solution with an industry partner to deal more effectively with its customer complaints.

- Regulatory Laws & Reform

New laws, licenses or amendments of existing laws to capture economic functions are introduced in response to innovative firms or business models. Some countries have used the development of new laws to expand their mandate and to build capacity and accountability while supporting the development of more discreet, secondary reforms, and amendments to frameworks. Often regulatory approaches might eventually lead to regulatory reform. Examples include overarching change such as the Mexico Fintech Law and incremental changes to regulation such as South Korea’s approach to e-money.

So where should policymakers start?

Policymakers should first and foremost consider their individual country context and evaluate if some “quick wins” are achievable. For example, in response to the sweeping pandemic and the need for digital payments, a number of countries—such as Ghana, Kenya, Saudi Arabia, and Uganda—have changed the limits on mobile money transactions. Ethiopia has paved the way to allow non-banks to offer basic financial services, opening the door for operators to potentially add mobile money to their portfolios. Other areas to be assessed include the institutional mission and policy priorities, the legal and regulatory framework, and the maturity of the fintech segment.

Our research indicates that Innovation Hubs—which have been used instead of or as a complement to Regulatory Sandboxes—have shown promise of being more effective and suitable to most business needs. Hubs can also be established quickly and with minimal resources, which may be valuable now, to help regulators better respond to market changes including instability caused by the crisis.

But because there so many pieces at play when debating and deciding the regulatory approaches to be considered, there is no “one “perfect solution”. Just like the process of iteration needed to hone a perfect business model, the approaches need to be refined over time and adapted to their own context.

The COVID-19 crisis, while devastating, can bring opportunity for improvement and change—particularly at a time when digital financial services can help reduce the spread of the disease. The interdependence of our financial systems and the global dimension of crises such as the current pandemic demand that we collectively strengthen our efforts in knowledge sharing and coordination. Policymakers should enhance their mechanisms to co-innovate, share experience, and coordinate their efforts to promote an orderly adoption and integration of innovation that will benefit all.

Join the Conversation