Would it surprise you to know that one in three women worldwide have experienced physical or sexual violence from their intimate partner? Or that as many as 38% of women who are murdered globally are killed by their partners? It is a sad reality, but those are the facts.

Globally, the most common form of violence against women is from an intimate partner. The statistics are shocking. And while these numbers are widely disseminated, the facts persist. The stories repeat themselves, affecting girls and women around the world regardless of race, nationality, social status or income level.

This sad reality was the cause of Nahr Ibrahim Valley’s death in Lebanon, just months after the country's new law on domestic violence was finally passed. The new law came after several cases sparked campaigns and protests in the Lebanese capital surrounding International Women’s Day last year. Unfortunately, it was not enough to save her life, but it can be the hope for thousands of women in the country, who previously had no legal protection against this type of crime.

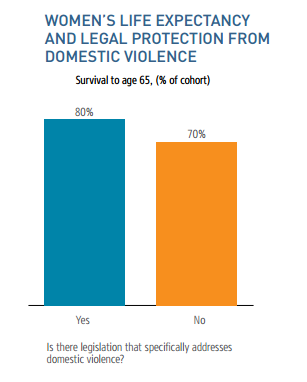

The World Bank Group’s Women, Business and the Law project studies where countries have enacted laws protecting women from domestic violence. The fourth report in the series, Women, Business and the Law 2016: Getting to Equal, finds that more than 1 out of 4 countries covered around the world have not yet adopted such legislation. The effects of this form of violence are multifold. It can lead to lower productivity, increase absenteeism and drive up health-care costs. Moreover, where laws do not protect women from domestic violence, women are likely to have shorter life spans.

Domestic violence, also viewed as gender-specific violence, commonly directed against women, which occurs in the family and in interpersonal relationships, can take different forms. Abuse can be physical, emotional, sexual or economic. The 2016 edition of Women, Business and the Law shows that, even where laws do exist, in only 3 out of 5 economies do they cover all four of those types of violence. Subjecting women to economic violence, which can keep them financially dependent, is only addressed in about half of the economies covered worldwide.

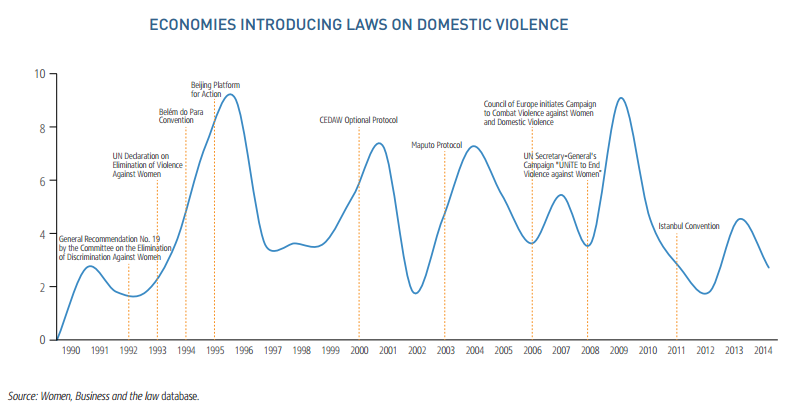

As with most present-day facts, this issue has historical roots, largely based on social and cultural norms. Before the 1900s, in most cultures, husbands had the right – by law – to use violence to enforce authority over their wives. The husband’s right to "physically discipline his wife" started slowly being removed in the late 19th Century. In 1878, the Matrimonial Causes Act in the United Kingdom made it legal for women victims of violence in marriage to obtain separation orders and, by the end of the 1870s, most United States courts had rejected the right of husbands to chastise their wives. In the 1970s, specific laws against domestic violence started being introduced, but it was only in the 1990s that they started gaining strength worldwide, largely driven by international and regional human-rights conventions and campaigns.

Around the world, increased awareness and a rising outcry surrounding cases of domestic violence call for the enactment of more and better laws. Legal protection against domestic violence in its various forms is crucial to reduce impunity and to open avenues for redress.

On the extreme end of this spectrum are countries that still legally allow for domestic violence. As recently as 2010, a court in the United Arab Emirates ruled that a husband is permitted to beat his wife as long as he leaves no marks. But awareness has been growing around the issue, and campaigns pushing for the enactment of laws and for the elimination of violence against women are increasingly prominent.

October is National Domestic Violence Awareness month in the United States. While the passage of the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) has enabled women to seek support and judicial response, cases of domestic violence are still widespread. The economic costs are also huge: Each year in the United States, eight million days of paid work are lost to domestic violence, amounting to some $8.3 billion in expenses. The adoption of the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA), as with similar laws around the world, can change people’s views regarding the seriousness of the offense and can enable victims to obtain support.

The good news is that progress is continuing. In addition to Lebanon, within the last two years Belarus, Latvia, Saudi Arabia and Tonga enacted laws on domestic violence for the first time. And other countries – such as Italy and Macedonia – have amended their legislation to cover economic violence.

Campaigns and awareness-building around the world have played a critical role in promoting the enactment of laws and behavior change over the past 25 years. Let’s continue the work to enable even better results toward eradicating all forms of violence against women in the next 25.

Join the Conversation