A cityscape of Mumbai

A cityscape of Mumbai

This blog post was first published on Brookings’ Future Development platform.

These three words are probably the most used in popular and policy discussions of city development. The squalor of slums, unsustainability of sprawl, and sterility of skyscrapers are the proverbial Achilles heel of community leaders and urban planners. They call for livable neighborhoods with a vibrant mix of homes, shops, offices and local amenities.

In a recent report, Pancakes to Pyramids: City Form to Promote Sustainable Growth, we examine how cities across the world have grown over the past quarter century and explain why some are stuck with slums, while others have expanded and some have built impressive skylines. Our priors have been shaped by our experiences living in cities, and we set out to examine if empirical regularities were consistent with these priors.

Three priors, one question

One of us recalls riding Mumbai’s crowded suburban rails during the early 1990s, passing the large slums of Dharavi, where people lived cheek by jowl with little access to taps and toilets at home. While India’s economy was opening up to new investment, authorities responsible for Mumbai were slow to lay in the infrastructure and streamline the regulations that made it easier for newcomers to live and set up business. To be sure, Mumbai’s skyline has peaked over the past three decades, with redevelopment comprising a quarter of all real estate development over the last 10 years (Gandhi et al 2021). Redevelopment of the city responded to economic demand. However, there is a long path ahead to ensure that slums of Dharavi transform into livable neighborhoods.

Around the same time, another one of us was growing up in Anyang, 15 kilometers from Seoul, and recalls catching frogs in rice fields with his friends. He recalls that “going to Seoul was a big deal—an annual event.” However, very soon, Seoul expanded into Anyang to accommodate its growing economy and population, building outwards and upwards. Rice fields gave way to skyscrapers, keeping in step with Korea’s rapid economic growth (See Figure 1).

| 1980s |

1990s |

2020 |

| |

|

|

Figure 1: Anyang, South Korea

The third among us grew up in a single-family home in a dormitory village of about 1,000 people around the city of Caen, one of the rainiest parts of France. She moved to Paris as a young adult, a city that she had always dreamt of living in. Her dreams were shattered as she realized that, as a student, she could not afford the cozy apartment under the roofs of the Left Bank district. She ended up living in the suburbs, in the "Red Belt" of Paris, with its Lenin-ish stadiums and high towers with concentrated poverty, which share some the most expensive land in Europe with expensive, single family homes that only a select few can afford. However, the Ligne 13 on the Métro allowed her to enjoy the human density and amenities of Paris.

Our experiences living in cities shows that the way a city grew reflected broader processes of economic development. If a country was poor and its economy stagnant, cities were crowded and squalid. As a country’s economy expanded, cities became home to a larger number of people and businesses who could demanded better homes, offices, infrastructure, and open spaces. Cities accommodated changes in demand by redeveloping their existing structures, by expanding into the periphery, and by building taller. Regulations could stymie the supply of structures and push poorer people into farther locations. But decent transport systems could keep them connected to opportunities. A growing economy interacting with urban regulations and transport systems shaped how a city grew. The question is: Was our experience shared across cities?

Floor space—the final product of urbanization

To answer this question, we carried out an empirical exercise to examine how floor space has evolved across cities and what factors contribute to a growth in floor area. We focused on floor space available in the city rather than its land area, as floor space makes the difference between a city being livable or being crowded. As the noted urbanist Alain Bertaud puts it, the final product of urbanization is floor space.

We answered this question in two parts. First, we estimated how the built-up area of a city has changed over the past 25 years, from 1990–2015. Then we identified what cities’ building heights look like across the world. To get a handle on built-up area growth, we examine data from 9,500 cities from the Global Human Settlement Urban Center Database. Details on measurement are provided in the report and in our working paper.

We find that livable floor space hinges on city growth along three margins:

- Horizontal spread—extending beyond the city’s previously built-up area

- Infill development—closing gaps between existing structures

- Vertical layering—raising the skyline of the existing built-up area

As cities grow in productivity and in population, they add floor space by expanding outward, inward, upward, or - more usually - along all three margins to varying degrees. We use the terms pancakes and pyramids as shorthand for two broadly different tendencies in the physical manifestation of city growth:

- Cities with low productivity and income levels and dysfunctional policy environments generally grow as pancakes—flat and spreading slowly. Low economic demand for land and floor space keeps land prices low and structures close to the ground, especially at the urban edge. Given slow expansion, growth in population density is often accommodated by crowding, starkly visible in the slums of developing country cities.

- Cities with higher productivity and responsive policies may evolve from pancakes into pyramids—their horizontal expansion persists, yet it is accompanied by infill development and vertical layering. A rising demand for floor space in economically productive cities, and rise in housing investment and consumption, leads developers to fill vacant or underused land at and within the city edge with new structures. The same demand for floor space drives expansion not just horizontally in two dimensions, but also in the third—the vertical. Structures are built taller, on average, and at the urban core they are built much taller, forming sharply peaked skylines.

The inevitability of sprawl, but with a silver lining

We find that horizontal growth is inevitable for most developing country cities. In low-income and lower-middle-income countries, 90 percent of urban built-up area expansion occurs as horizontal growth (Figure 2). But there is a silver lining: in high-income and upper-middle-income country cities, a larger share of new built-up area is provided through infill development. A city in a high-income country that increases its built-up area by 100 square meters will add about 35 square meters through infill development and 65 square meters through horizontal spread. But a similar city in a low-income country will add 90 square meters through horizontal spread and only 10 square meters from infill.

Figure 2: Horizontal growth is inevitable for most developing country cities

We also find that economic productivity and rising incomes are indispensable for vertical layering, because building high is capital-intensive. A city that grows in population, but not productivity and incomes, will not generate enough economic demand for new floor space for its spatial expansion to keep pace with population growth. For example, if population were to increase by 10 percent but incomes stayed constant, the city’s total floor space would increase by 6 percent. This 6 percent increase is too small to allow a newly added population the same amount of floor space per person as before: Each inhabitant’s residential and workspace will shrink, eventually making the city less livable. Our estimations indicate:

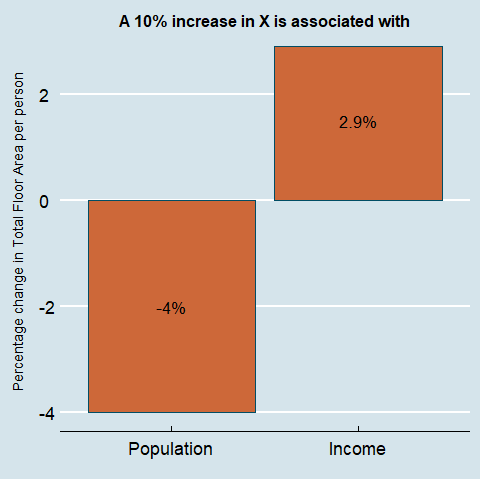

- The elasticity of total floor space to population is 0.60. If a city’s population increases by 10 percent (holding income constant), its total floor space increases by 6 percent because of built-up area increase (3.5 percent) and vertical layering (2.5 percent) (Figure 3).

- Elasticity of total floor space to income: 0.29. If the city’s income increases by 10 percent (holding population constant), its total floor space increases by 2.9 percent through a combination of built-up area expansion (1 percent) and vertical layering (1.9 percent).

Figure 3: Horizontal growth is inevitable for most developing country cities

Increasing incomes and economic productivity are together necessary for a rise in floor space per person through vertical layering and pyramidal growth. Our research shows that the growth of cities and the availability of floor space reflect market forces that support productivity and economic growth. The finding echoes the World Bank’s 2009 World Development Report on Economic Geography: “Many policy makers perceive cities as constructs of the state—to be managed and manipulated to serve some social objective. In reality, cities and towns, just like firms and farms, are creatures of the market.”

Slums, sprawl, and skyscrapers reflect market conditions but are generally distorted by poor regulation and inadequate infrastructure. The movement out of slums towards livable cities is critical for developing countries, but this is unlikely to happen without structural transformations and economic growth.

Join the Conversation