Artificial intelligence (AI) can help developing economies diversify science formula and math equation abstract background

Artificial intelligence (AI) can help developing economies diversify science formula and math equation abstract background

Artificial intelligence (AI) is considered a general-purpose technology that, like electricity, could transform our lives. AI technology can detect symptoms related to the early stages of cancer, predict the next virus mutation, create works of art, plan your investment portfolio, and even help craft this blog. The growing number of AI applications promises to transform the concept of what we consider a human job.

Small wonder, then, that countries worldwide are racing to harness AI to make their industries more competitive in export markets and discover new areas of comparative advantage. The effort is particularly important for developing economies, which often rely on exports to drive growth but may be dependent on a handful of products or commodities. For these economies, diversification offers a pathway to new sources of growth and makes them more resilient to unexpected shocks—much as a diversified portfolio investment is more stable than a single security.

So, how can developing countries leverage AI to achieve faster, more sustainable growth? Our new paper, AI Specialization for Pathways of Economic Diversification, provides a possible answer. The paper, cowritten with Robert Koopman, Giuditta de Prato, Keith Streir, Julie Kim, and Nikola Spatafora, presents quantitative evidence of the linkages between different forms of AI and a country’s comparative advantage.

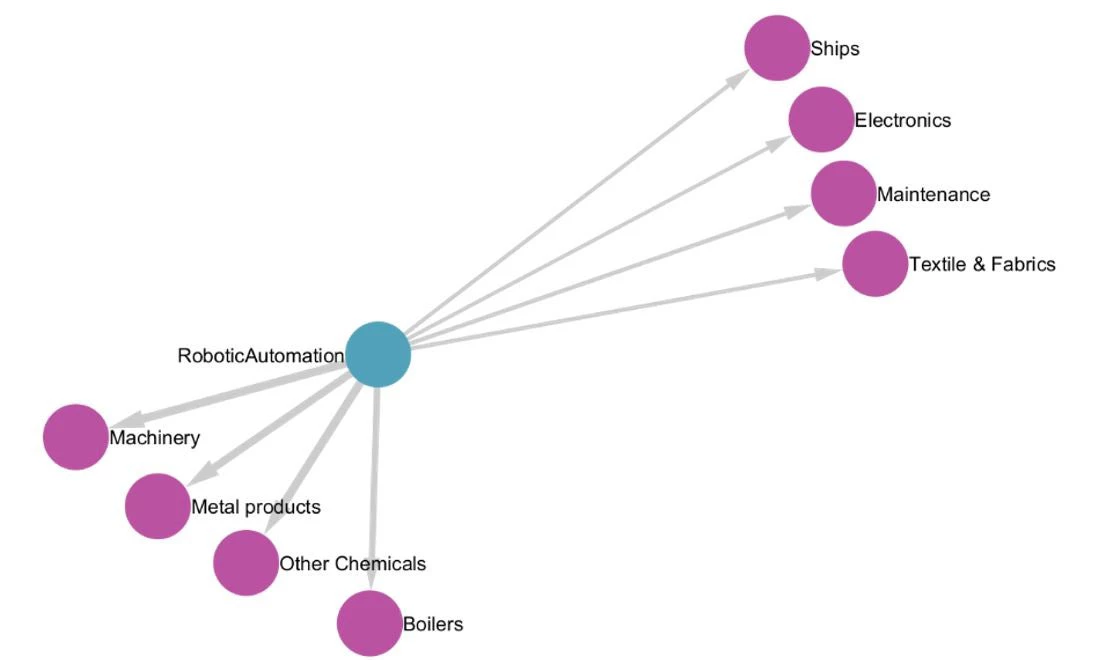

In the paper, we drew on an economic principle known as the product space to identify areas where a country may have a comparative advantage and potential for expanding its economic activities. We built a new database of private investments in AI classified into 29 categories such as autonomous vehicles, agri-tech, robotics, and gaming/e-sports. We then measured each country’s AI specialization and constructed a network linking AI with comparative advantage patterns in goods and services.

The network reveals that each type of AI technology has stronger links with some sectors than others. For instance, robot automation has strong connections to the manufacture of machinery, metal products, chemicals, and boilers. Image recognition and visual search favor industries like food processing (helping distinguish between good and bad staples) or e-commerce (enabling customers to find products by simply taking pictures).

For each country, we ranked sectors with growth potential, accounting for specialization in AI, goods, and services. The results suggest ways for developed and developing countries to leverage AI specialization to diversify their sources of comparative advantage.

For instance, our findings suggest that by investing in robot automation, Mexico could strengthen the fabrication of metal products; investments in FinTech related to booking and payment systems would allow Mexico to maintain its edge in travel services. For India, investments in AI agricultural technology could help increase its farmers’ productivity.

As demand for AI-based services increases, improvements in communication technology make it possible for many AI solutions to be “manufactured” in one location and operated and maintained elsewhere. For example, KUKA Robotics is a German firm whose industrial robots integrate various AI functions such as machine learning, vision systems, and sophisticated control algorithms.

Kuka’s robotic systems are deployed in numerous countries across diverse industries, such as automotive, aerospace, and electronic manufacturing. AI solutions could be deployed at every step of the production process, from research and development to production, distribution, repair, and recycling. The future wealth of nations could depend on having a broad base of AI services that strengthen participation in existing global value chains.

Figure 1: AI in Robot Automation is strongly linked to industries in the manufacturing sector from textiles to machinery and ships.

Join the Conversation