Emerging market multinationals (EMMs) have become increasingly salient players in global markets. In 2013, one out of every three dollars invested abroad originated from multinationals in emerging economies.

Emerging market multinationals (EMMs) have become increasingly salient players in global markets. In 2013, one out of every three dollars invested abroad originated from multinationals in emerging economies.

Up until now, we have had a limited understanding of the characteristics, motivations, and strategies of these firms. Why do EMMs decide to invest abroad? In which markets do they concentrate their investments and why? And how do their strategies and needs compare to those of traditional multinationals from developed countries?

In a book we will launch tomorrow at the World Bank, “New Voices in Investment,” we address these questions using a World Bank and UNIDO-funded survey of 713 firms from four emerging economies: Brazil, India, Korea, and South Africa.

We designed our survey to go beyond previous efforts to study foreign investors—by also including potential cross-border investors. These are firms that considered investing and decided not to, or companies that never considered establishing a foreign presence. As Hausmann and Velasco once quipped, asking only camels about the living conditions in the desert will give you a completely different concept than asking hippos.

Our survey addresses this problem, by interviewing these potential investors—the hippos, in this scenario—in their countries of origin. Doing so reveals differences in incentives and obstacles faced by investors, potential investors, and non-investors. These are distinctions that matter enormously, particularly in identifying the binding constraints on foreign investment that eventually led some firms not to invest.

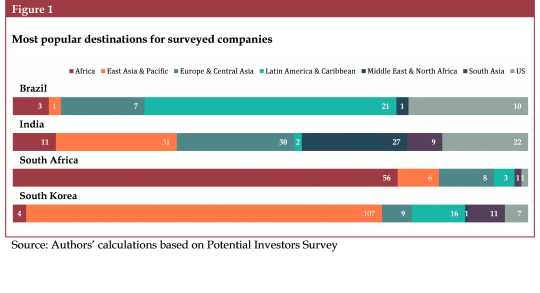

A number of findings emerge from the study. First, a clear pattern of regional concentration is unveiled by our analysis, particularly in investment in the services sector. While some analysts have stressed the greater geographical dispersion of the recent wave of outward foreign direct investment (FDI) flows from emerging economies, we find that firms in our sample invest more heavily in neighboring countries, where they face lower informational costs and cultural barriers. Yet, there is cross-country heterogeneity. Firms from India appear to be more globalized than their counterparts from Brazil, South Africa, and Korea, investing more heavily in East Asia and Europe than in the South Asia region.

Second, much like developed-country multinationals in previous waves of FDI expansion, emerging market investors are market and efficiency seeking. When we asked firms in our sample about their main motivations for investing abroad, 70 percent said they sought to access new markets and another 20 percent of investors were motivated by lowering production costs, thus gaining efficiency. Less than 5 percent of firms invested abroad to gain access to natural resources.[1]

EMMs’ concern with taking advantage of opportunities for market and business expansion in developing countries was also evident when analyzing the factors that influence their location decisions. Almost 36 percent of investors selected the size of the domestic and regional markets as the top factor influencing the choice of an investment destination. For 30 percent of the firms surveyed, the presence of a variety of potential business counterparts was the most important location factor. A sizeable proportion of respondents (12 percent) worried primarily about the cost of labor. By contrast, EMMs seem less concerned about non-economic factors, such as political risk and cultural affinities, when deciding where to invest (Figure 1).

Does this mean that EMMs are relatively immune to political risk or regulatory uncertainty? It has been argued that multinationals from EMMs have an “adversity advantage” due to being exposed to those conditions in their home countries in the first place. But when comparing the importance attributed to political risk by actual and potential investors, a different picture emerges. While only 6 percent of investors and 10 percent of those considering investing abroad ranked political risk and cultural factors as top location factors, more than 20 percent of non-investors identified these as the main considerations influencing the decision not to invest. Political risk and cultural dissimilarities thus appear to constitute binding constraints that deter some emerging-market firms from investing in developing markets. Far from being immune to political risk and cultural uncertainty in host markets, those firms that are more averse to these conditions seem to self-select out of foreign investment.

These findings have implications for policymakers seeking to increase inflows of FDI. By deepening integration in the global marketplace through trade and investment and expanding opportunities for participation in regional production networks, governments of developing countries can help increase investment by existing firms, that is, promoting investment growth along the intensive margin.

Yet, attracting new firms, that is, promoting investment growth along the extensive margin, requires addressing other binding constraints, such as poor governance, a weak regulatory and legal environment, and high informational and transaction costs associated with cultural specificities. A progressive reduction of transaction costs and political risk could make potential investors cross the line into actually investing.

Join the Conversation