Differentiating between effective and nominal access

A couple of months ago, one of our urban development colleagues wrote about the gap between effective and nominal access to water infrastructure services. She explained that while many of the households in the study area were equipped with the infrastructure to supply clean water, a large number of them do not use it because of its price. She highlighted a “simple fact: it is not sufficient to have a service in your house, your yard, or your street. The service needs to work and you should be able to use it. If you can’t afford it or if features—such as design, location, or quality—prevent its use, you are not benefiting from that service.” To address this concern, the water practice has been developing ways to differentiate between “effective access” and “nominal access”—between having access to an infrastructure or service and being able to use it.

In transport, too, we have been exploring similar issues. In a series of blog posts on accessibility, we have looked at the way accessibility tools—the ability to quantify the opportunities that are accessible using a transit system—are reframing how we understand, evaluate, and plan transport systems. We have used this method that allows us to assess the effectiveness of public transport in connecting people to employment opportunities within a 60-minute commute.

Incorporating considerations of cost

Yet, time is not the only constraint that people face when using public transport systems. In Bogota, for example, the average percentage of monthly income that an individual spends on transport exceeds 20% for those in the lowest income group. In some parts of the city, this reaches up to 28%—well above the internationally acceptable level of affordability of 15%.

Given that the cost of the transit system might be a major barrier to accessing opportunities, we have also looked into identifying measures of accessibility that factor in budget or affordability constraints. To do so, we built upon the previous accessibility model by adding another binary threshold to the equation that used the cost of the trip, a location is only considered to be accessible if it can be accessed within the travel and cost budget. As a result, we consider opportunities to be accessible and affordable only if they are within a given trip time and cost.

How does it work in practice?

We are testing this feature in Bogota. In 2011, the city started implementing the Integrated Public Transit System (SITP for its Spanish acronym), which includes a restructuring of its transport services, a change in the fare structure, and major discounts on transfers between transport modes (BRT and local buses).

We tested two different budget constraints to potential accessibility, a COP1700 and a COP2000 budget. This represents a 9-14% and 10-17% of monthly income, respectively, spent on transit by those in the lowest income group.

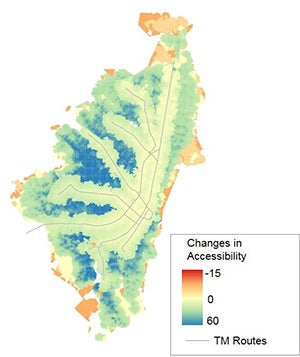

Most notable are the results based on the COP2000 budget. Compared to the previous system that required a full fare for transfers, the current tariff—which allows passengers to use the SITP and make one transfer—increases overall accessibility in the city. This is of particular importance to the population in the lowest income groups, which live in the peripheries of Bogota and will see the biggest gains in accessibility, including to employment opportunities.

Changes in affordable employment accessibility, before and after the SITP, using 60min and COP2000 budget constraints

Effectively, this new feature of the tool allows us to compare and evaluate the effects of budget constraints that poor people face when trying to use the transit system and access opportunities. It also allows us to compare different fare policies on similar terms.

Nevertheless, time and cost are not the only constraints that people face in accessing opportunities. Moving forward, we want to integrate other dimensions into the tool, to help account for factors such as quality of service, reliability, and safety.

Do you have suggestion on other dimensions and factors that we should try to include?

Join the Conversation