Increasing numbers of citizens all over the world are demanding that urban planners and political authorities in their cities “get it right” when designing public urban spaces. People living in cities, both in developed and developing countries are reclaiming streets as public spaces, demanding urban planners to re-design streets to ensure a more equitable distribution of these public spaces, and prioritizing the allocation of streets for people to walk, cycle and socialize. This was the central topic discussed last week at the “Future of Places” conference in Buenos Aires, Argentina.

How do we contribute to a more equitable society by building more equitable cities? In an increasingly urbanized world, urban mobility is central to citizens’ social and economic wellbeing. However, current urban transportation systems – based primarily on the movement of private motorized vehicles – have prioritized road space and operational design of streets for automobiles over other modes of transport, which has caused many social, environmental and economic consequences, therefore reducing urban livability and equitable access.

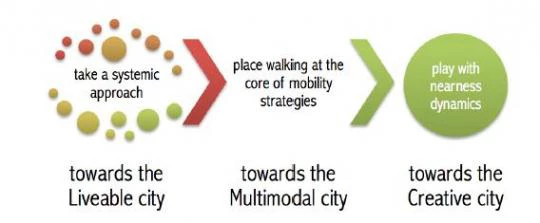

The values of urbanity and mobility are being rethought all over the world, and Latin American cities are no exception to this questioning of how cities are to be developed today. One of the answers to sustainability issues lies in the concept of proximity, which combines different dimensions of the urban proposals that the 21 st century requires. These dimensions include public health – particularly the fight against sedentary habits – as well as density, compactness, closeness, resilience, and livability of the public space. These all point to a new urban paradigm that all creative cities wish to adopt in order to attract the knowledge economy and guarantee social cohesion.

to integrated, walkable urban spaces.

In order to boost productivity and innovation, creative cities are designing pedestrian environments at a more human scale, in connection with a wide range of sustainable urban transport options. The knowledge economy demands places that are rich in serendipity for chance encounters between diverse people. Spaces and relationships between people are being reinvented; metropolitan dynamics today play with both distance and proximity.

The broadening of the functional city’s scope leads, paradoxically, to a return to nearness dynamics for some of our daily activities. In this context, it is extremely important to learn how to design new spaces that accommodate new ways of moving freely within the city and enjoying everything it has to offer.

The World Bank is working on these precise topics with several of our partners in Latin American cities, coordinating efforts to address mobility needs, road safety, agglomeration efficiency, inclusiveness, and environment issues at the local level, in order to boost shared prosperity and reconcile mobility with quality of life and environmental sustainability. We are working around a holistic approach, emphasizing a key message: sustainable mobility is about a convergence of agendas, mobility that is healthy, safe, affordable, equitable, universal, efficient, and clean.

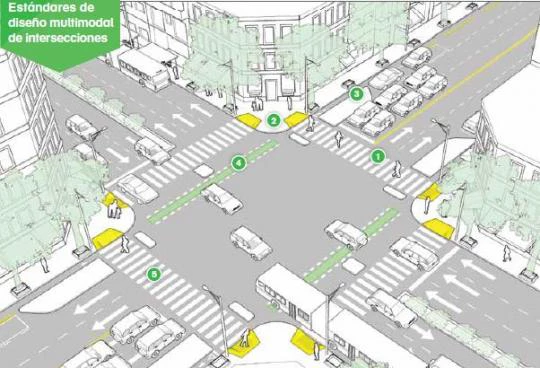

It is also a response to some of the more intractable problems associated with urban poverty, not only in terms of access to economic opportunity, but also taking into account the broader dimensions of social inclusion through improved access to schools, health facilities and wider social interaction. Here are some of the key findings of recent work on “walkability in a multi-modal city,” carried out in partnership with ITDP and the City of Buenos Aires, which led to the publication of a street design manual:

- There are plenty of examples of what a livable city focused on people looks like. On the road from theory to practice, each city finds its way to its own solution. It’s this collection of simple design fixes that should be both recognized and registered to define each city’s path to a more sustainable and healthier design, with feasible and achievable local solutions.

- Walking, in connection with multimodal strategies, is part of the answer in building sustainability in transportation. Cities like Buenos Aires have everything to gain from encouraging pedestrian strategies, as their leverage effect is essential to the shift towards more sustainable mobility.

- As cities urbanize and densify, you need to provide spaces and opportunities for people to relax, breathe, connect and build communities, in order to maintain a certain quality of life. Urban amenities, as widely as you may want to define the word, are an essential part of the integrated urban space. They are key to making urban agglomerations work, and should be included in the early planning phases of an urban space rather than an afterthought, as they are more difficult to implement and much more expensive to set up.

- Urban amenities can contribute positively or negatively to inclusion: if amenities are conceived to attract very specific segments of the population (exclusive commercial spaces, high tech buildings, expensive museums), what they will tend to do in the long run is promote gentrification. As a result, urban amenities should be well planned so that they promote inclusiveness and mingling of diverse races and income groups, therefore promoting the creation of communities and providing opportunities for everyone to enjoy pretty, educational, fun, safe, clean, and healthy urban public spaces.

- Lack of policies or institutional coordination for city planning and development have led to unequal layouts of infrastructure that frequently affect densely populated areas where the population is more vulnerable, has less economic resources and lack basic services. Reduction in access to public spaces and unclear boundaries between the public and private spheres can limit democracy. There is a need for a new paradigm that should recognize the inability of the market to ensure the creation of a hierarchy of public and private open spaces protected over time.

- In addition to these pervasive infrastructure problems, there is a lack of integrated information systems for data collection. The development of reliable, ongoing, integrated data collection systems is key, for instance, in evaluating infrastructure interventions and informing urban and transport safety policies based on evidence. We are using the existing safety-related information from the City of Buenos Aires coupled with the recent pedestrianizing of the city’s microcenter, bike lanes and the BRT expansion to evaluate more carefully the effect of these large infrastructure investments and their relationship to crime, violence and transport injury modifications.

- Citizen engagement is key to effectively plan and implement better public spaces; new technologies (crowdsourcing, open data, etc.) can have transformational impacts in terms of engaging intelligently with citizens. Emphasis needs to be placed on a shared responsibility between community and private entities in regards to the maintenance of public space.

What characterizes the discussion amongst city planners and decision makers today is not the lack of awareness of what direction they should take, but rather the connection between that awareness and their actions. Considering lock-in effects and the higher costs of re-designing and correcting flawed approaches, there’s an urgency to enhance governments’ capacity to further develop a “people-oriented” focus in their planning processes, rooted in a vision of a more livable city with a strong sustainability profile.

We’ll tell you more about the results of this work as we move ahead, and would welcome your thoughts.

Join the Conversation