Few concepts are as abstract as “social inclusion”. No wonder it generates questions, confusion and even some misunderstandings among practitioners.

Since social inclusion is a pillar of sustainability and part of new World Bank Goals of reducing poverty and promoting shared prosperity, the term has come into even greater usage. But what is it? We define social inclusion as the process of improving the terms for individuals and groups to take part in society. People take part in society through markets (e.g. labor, or credit), services (access to health, education), and spaces (e.g. political, physical).

Based on the background work conducted by the Social Inclusion team from Social Development for an upcoming report Inclusion Matters: The Foundation for Shared Prosperity, below are four of the most common misconceptions about social inclusion and exclusion.

1. Social exclusion is synonymous with inequality and poverty

While inequality and poverty are outcomes, social exclusion is both an outcome and a process. Social exclusion is often more than poverty and in some cases it is not about poverty at all. Further, while concepts such as poverty and inequality often have material conditions associated with them, social inclusion is to a large extent about non-material aspects of a person’s life. Take for example a hypothetical homosexual man living in a rich neighborhood. He may not be poor, he may not even be affected by inequality, but he is certainly excluded, and in some countries, at risk of death. One’s identity can be a primary marker of exclusion.

2. Social inclusion is the flip side of social exclusion

Although it sounds logical and intuitive, inclusion is not necessarily the flip side of exclusion. Here is why.

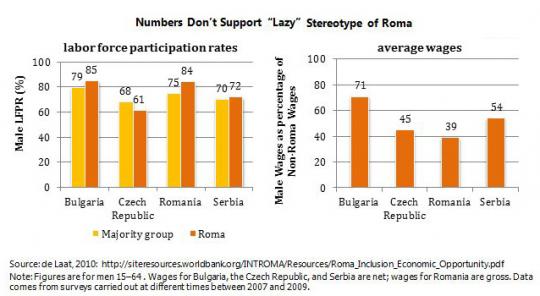

Social exclusion occurs when people are systematically prevented from taking part in society. But individuals and groups may have to participate in markets, services, and spaces under unfavorable terms. This is called “adverse inclusion”. For example, immigrants may be included in the host country’s labor market, but under very poor working conditions and for a wage lower than is paid to local residents. Take the case of the Roma who are part of the labor force but are paid less. Roma males have higher labor force participation rates than the majority group in Bulgaria, Romania, and Serbia, yet their average wages are just 40-70% of the non-Roma men. If you can call this inclusion, then it is inclusion under very disadvantageous terms.

3. Social inclusion is mainly a developing country issue

Challenges related to social exclusion are not distinctive to developing countries. People all over the world face exclusion, discrimination, or chronic poverty. In many developed countries, the discourse around immigrants and restrictions for them to get access to markets and benefits is highly debated. Almost all European countries are dealing with issues of inclusion because of their need for foreign labor and yet immigrants are often discriminated against. Pick most any country and you will find issues of inclusion never fully addressed or new ones constantly emerging.

4. We should rely only on objective/economic indicators when measuring social inclusion.

More and more, subjective measures (of happiness, attitudes and perceptions, for example) have gained interest among policy makers around the world. They are helpful in diagnosing social inclusion and tracking progress over time. And if analyzed in tandem with objective indicators, they can explain why some people get left out from progress.

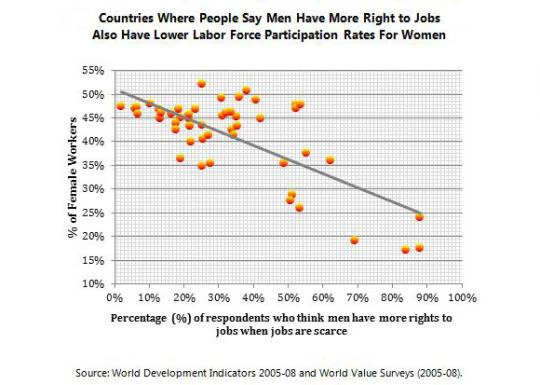

Attitudes matter because they are a barometer of people’s potential behavior. Attitudes and perceptions can determine who gets excluded and included in the society and how. When certain attitudes become widespread they can affect the way people and institutions treat others, and the way policies are implemented or even designed.

For example, World Values Survey asks respondents whether they think men should be given preference for jobs when jobs are scarce in the economy. This question reflects social norms of men as breadwinners and has impact on women’s economic empowerment. Respondents in a vast majority of countries believe men should be given preference. In fact, the most discriminatory attitudes are found in countries that have the lowest female labor force participation rates.

We invite you to join the conversation about social inclusion on Facebook and Twitter #inclusionmatters. Tell us what inclusion means in your country. Tell us what inclusion means to you.

The report Inclusion Matters: The Foundation for Shared Prosperity will be launched on October 9, 2013. Learn more about social development and social inclusion.

Join the Conversation