This week is unique. December 1 was World AIDS Day –a moment to unite with the community touched by HIV and push forward in the fight. December 4 is Ocean Day at COP21 – an opportunity to advance the global ocean and climate agenda toward meaningful impact and action. Two important days with two very different purposes. And yet, each significant in commemorating critical causes that are often just outside the realm of everyday consideration. But it is not only this marginality that links them– and understanding this connection can only strengthen our imperative to act.

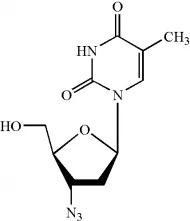

The first HIV medicine

Azidothymidine (or AZT) was the first ever antiretroviral approved treatment for HIV. Its release in 1987 was watershed, providing widespread opportunity for fighting the disease and giving hope to those many thousands facing death sentences. Though recognized to be imperfect when prescribed alone, it paved the way for other medications and has gone on to be used in standard practice therapies which diminish viral load, maintain a healthy immune system, and prevent other opportunistic infections. AZT has also been used in HIV prevention – originally in post-exposure prophylaxis and now commonly in pre-exposure prophylaxis, serving the critical function of preventing mother-to-child HIV transmission. Since the drug came to market, it has improved and prolonged the lives of countless people with HIV and helped prevent millions of new cases.

AZT is similar in structure to thymidine, one of the four fundamental nucleoside building blocks of DNA. When AZT is incorporated into growing DNA instead of thymidine, the chain stops and the DNA is unable to replicate- preventing the proliferation of cells infected with virus.

AZT is similar in structure to thymidine, one of the four fundamental nucleoside building blocks of DNA. When AZT is incorporated into growing DNA instead of thymidine, the chain stops and the DNA is unable to replicate- preventing the proliferation of cells infected with virus.

Where did AZT come from? Was it manufactured in a laboratory or did we find it in nature like penicillin and aspirin? The answer, as is true of so many medications: both. Through organic techniques, AZT was synthesized in a US laboratory in the 1960s (originally intended as a cancer medication). But, the ability to do so was only possible following the discovery of new compounds found in the ocean.

The link to the sea

In 1945, a young organic chemist named Werner Bergmann collected a previously undescribed sponge in the waters off of Florida, which was eventually taxonomized as a new species, Tectitethya crypta. Through experimentation, Dr. Bergmann discovered that these sponges possessed a new compound unknown to science. The molecule was similar to, but not exactly like, thymidine (again, one of the building blocks of DNA). He named this new compound spongothymidine, in reference to the known compound it resembled and testament to the creatures from which it comes.

Less complex than humans, sea sponges lack immune systems and so evolved other compounds for survival, such as spongothymidine, to protect against invading pathogens, precisely in the way that AZT has been designed to do, following their mechanism and model.

In fact, the discovery of nucleoside analogues like spongothymidine has led to the development of other drugs that act in the same way but protect against different diseases. Collectively, these have had a profound global health impact. Aciclovir (ACV), for example, treats herpes, chickenpox, and shingles and cytarabine (Ara-C) is a key component of cancer therapy for acute leukemias and lymphomas. Both are included on the World Health Organisation’s List of Essential Medicines (drugs that should be available at all times because of universal need).

Connecting the ocean and health for development

Recognizing this link between human health and the ocean is important because it clarifies the incalculable value our marine resources and highlights how truly fundamental the global ecosystem is to our narrative as humans. HIV and other diseases are often perceived as fundamentally “human” issues. And yet, many of these diseases have emerged through our interactions with the natural world (i.e. HIV from primates). So have the solutions (i.e. the medications we have used to fight them).

Human existence is a balance between illness and health – and unfortunately, continued environmental degradation tips this in an unfavorable direction. Air pollution hastens climate change and causes millions of respiratory-related deaths every year, deforestation increases the possibility of emerging infectious disease transmission, and overfishing and ocean acidification threaten the largest and most life sustaining natural resource on the planet.

The World Bank has long been active in the fight against HIV. And we have separately for years been working to improve the sustainability of the ocean. Considering the ocean and health together focuses attention where it is most relevant for our work: the overwhelming majority of the nearly 37 million people in the world living with HIV are in low income countries and of the more than 300 million worldwide that are dependent on sustainable ocean resources for survival, 97% are in the developing world.

We must recognize the interconnected web of natural resources and humanity and acknowledge how good environmental stewardship translates to more than maintaining beautiful national parks and marine reserves. Good environmental stewardship can also lead to better health, especially for those many people the World Bank is working to support.

At COP21, there is opportunity to improve the future prospects of both health and the ocean through meaningful international agreement. If not, climate change will continue to negatively impact the ocean and ultimately human health. We must press forward, identify solutions, and recognize this unique opportunity for shared global, environmental, and human impact.

Join the Conversation