Some Good News

The September 2014 issue of Food Price Watch reports that international food prices have declined to a four-year low, and in the last four months, these declines have fully reversed the price increases observed between January and April 2014. Prices of wheat and maize have plummeted amid constantly improving production outlooks and stronger stocks across the northern and southern hemispheres. Concerns from a few months ago related to tight import demand and geopolitical tensions have abated. An unfolding El Niño might not even have major production and price impacts given the current state of crops in the main producing countries. And a recent article in the Financial Times announced the slowing of food price inflation in rich and poor countries.

So, Why Are We Still Talking about Food Prices and Food Crises?

There are three good reasons: risks, stakes, and timing.

Risks, like energy, do not disappear, but they do change. Risks have by no means disappeared simply because prices have declined for four consecutive months. Looking just a little ahead, the arrival, length, and intensity of El Niño remain to be seen. If it finally arrives, El Niño could have serious consequences on major crops later in 2015, if it lasts longer than the average six to nine months. We do not yet know the effects of the Russian import ban on some specific, traded foods. The effects of a new Thai scheme that is replacing the suspended rice pledging program may well have lasting effects on domestic and, by extension, export prices of rice. This list of risks goes on and on.

The stakes continue to be very high. Food security-wise, we still live in a tough world. The Food and Agriculture Organization recently reported exceptional shortfalls in the production and access to food in 33 countries. Conflict and civil insecurity are expected to worsen the prospects for current crops in the Central African Republic, Somalia, and the Syrian Arab Republic. The Famine Early Warning Systems Network anticipates that South Sudan and Somalia may have food emergency episodes early on in 2015 due to lean seasons, flooding, displacement, and insecurity. The World Food Programme and the World Health Organization highlight that even though the effects of the Ebola Virus Disease on food prices are not yet fully grasped, specific markets report sharp increases due to trade and market disruptions in the three most affected countries. In this kind of world, sudden international price rebounds still have important consequences.

Now is the time to prepare for a crisis. Now that international prices are declining and may remain stable for a stretch, getting ready for the next crisis is crucial. During previous food price spikes, we learned the hard way that preparing for a food crisis after it begins is not an effective strategy for coping, mitigation, or prevention. Preparation must begin well before a crisis arrives.

There is no dearth of monitoring mechanisms to track the different dimensions of global, regional and local food insecurity; some of them date back as far as the early 1970s and were developed by the organizations mentioned above. But while existing systems provide vast amounts of data, information and analysis related to food security at different levels, currently none has the capacity to simultaneously monitor global- and national-level key indicators and also sound the alarm without extensive and laborious assessments. So even though humanitarian food crises and long-term food insecurity are recurrent phenomena, late responses—like the one seen in the Horn of Africa—are not isolated events.

Can We Do More Than Just Talk About It?

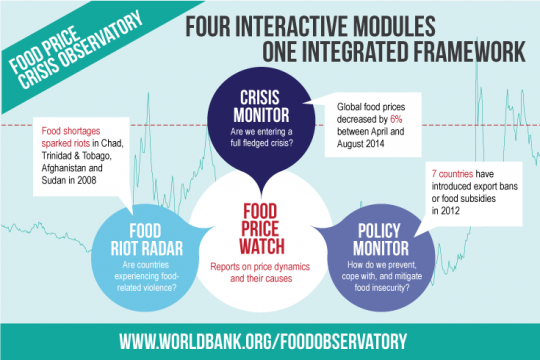

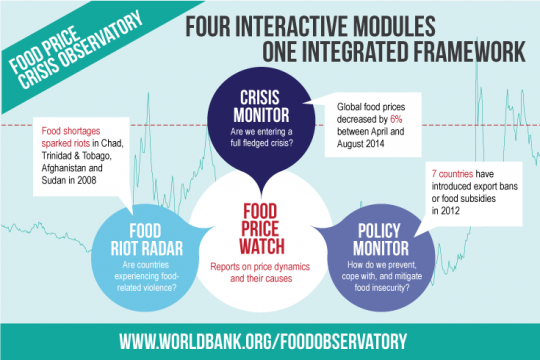

Yes, we can—and we should. We have recently developed the Food Price Crisis Observatory as a next step in food crisis preparation. This complementary monitoring system focuses on the poorest and most vulnerable countries, covered by the World Bank Group’s fund for the poorest, the International Development Association. The Observatory is built upon the concept of vulnerability and focuses more narrowly on price-related food crises. It not only follows international and domestic price trends closely, but also provides an evidence-based platform to identify when those trends begin translating into full-fledged crises; the sociopolitical consequences of such crises; and the interventions adopted (and those abandoned) to cope with, mitigate, and prevent food crises.

So if you want to know how far today’s international food prices are from a level that has historically signaled the start of serious trouble, click here. What is the exposure of your country and its neighbors to increasing domestic food prices, and what is the macroeconomic space they have to confront that situation? Click here. How many food riots have taken place since 2007 against the backsplash of current food prices? The answer can be found here. And how many countries introduced food subsidies in the face of the food price hikes in 2012? Find out here.

You do not need to be an expert on food insecurity, statistics, or information technology systems to find informed answers to these types of questions. After all, monitoring becomes truly a public good when it is accessible to everyone: the Food Price Crisis Observatory is another step in that direction.

The September 2014 issue of Food Price Watch reports that international food prices have declined to a four-year low, and in the last four months, these declines have fully reversed the price increases observed between January and April 2014. Prices of wheat and maize have plummeted amid constantly improving production outlooks and stronger stocks across the northern and southern hemispheres. Concerns from a few months ago related to tight import demand and geopolitical tensions have abated. An unfolding El Niño might not even have major production and price impacts given the current state of crops in the main producing countries. And a recent article in the Financial Times announced the slowing of food price inflation in rich and poor countries.

So, Why Are We Still Talking about Food Prices and Food Crises?

There are three good reasons: risks, stakes, and timing.

Risks, like energy, do not disappear, but they do change. Risks have by no means disappeared simply because prices have declined for four consecutive months. Looking just a little ahead, the arrival, length, and intensity of El Niño remain to be seen. If it finally arrives, El Niño could have serious consequences on major crops later in 2015, if it lasts longer than the average six to nine months. We do not yet know the effects of the Russian import ban on some specific, traded foods. The effects of a new Thai scheme that is replacing the suspended rice pledging program may well have lasting effects on domestic and, by extension, export prices of rice. This list of risks goes on and on.

The stakes continue to be very high. Food security-wise, we still live in a tough world. The Food and Agriculture Organization recently reported exceptional shortfalls in the production and access to food in 33 countries. Conflict and civil insecurity are expected to worsen the prospects for current crops in the Central African Republic, Somalia, and the Syrian Arab Republic. The Famine Early Warning Systems Network anticipates that South Sudan and Somalia may have food emergency episodes early on in 2015 due to lean seasons, flooding, displacement, and insecurity. The World Food Programme and the World Health Organization highlight that even though the effects of the Ebola Virus Disease on food prices are not yet fully grasped, specific markets report sharp increases due to trade and market disruptions in the three most affected countries. In this kind of world, sudden international price rebounds still have important consequences.

Now is the time to prepare for a crisis. Now that international prices are declining and may remain stable for a stretch, getting ready for the next crisis is crucial. During previous food price spikes, we learned the hard way that preparing for a food crisis after it begins is not an effective strategy for coping, mitigation, or prevention. Preparation must begin well before a crisis arrives.

There is no dearth of monitoring mechanisms to track the different dimensions of global, regional and local food insecurity; some of them date back as far as the early 1970s and were developed by the organizations mentioned above. But while existing systems provide vast amounts of data, information and analysis related to food security at different levels, currently none has the capacity to simultaneously monitor global- and national-level key indicators and also sound the alarm without extensive and laborious assessments. So even though humanitarian food crises and long-term food insecurity are recurrent phenomena, late responses—like the one seen in the Horn of Africa—are not isolated events.

Can We Do More Than Just Talk About It?

Yes, we can—and we should. We have recently developed the Food Price Crisis Observatory as a next step in food crisis preparation. This complementary monitoring system focuses on the poorest and most vulnerable countries, covered by the World Bank Group’s fund for the poorest, the International Development Association. The Observatory is built upon the concept of vulnerability and focuses more narrowly on price-related food crises. It not only follows international and domestic price trends closely, but also provides an evidence-based platform to identify when those trends begin translating into full-fledged crises; the sociopolitical consequences of such crises; and the interventions adopted (and those abandoned) to cope with, mitigate, and prevent food crises.

So if you want to know how far today’s international food prices are from a level that has historically signaled the start of serious trouble, click here. What is the exposure of your country and its neighbors to increasing domestic food prices, and what is the macroeconomic space they have to confront that situation? Click here. How many food riots have taken place since 2007 against the backsplash of current food prices? The answer can be found here. And how many countries introduced food subsidies in the face of the food price hikes in 2012? Find out here.

You do not need to be an expert on food insecurity, statistics, or information technology systems to find informed answers to these types of questions. After all, monitoring becomes truly a public good when it is accessible to everyone: the Food Price Crisis Observatory is another step in that direction.

Join the Conversation