She is one of many Indigenous women in Latin America who have dedicated their lives to creating more inclusive societies. While it is important to acknowledge that not all Indigenous groups and not all women have the same experiences, the concept of intersecting identities helps explain the concept of "additive" or "multiplied disadvantage" (or advantage). Individuals are part of multiple social structures and roles simultaneously, and these structures interact and influence experiences, relations, and outcomes.

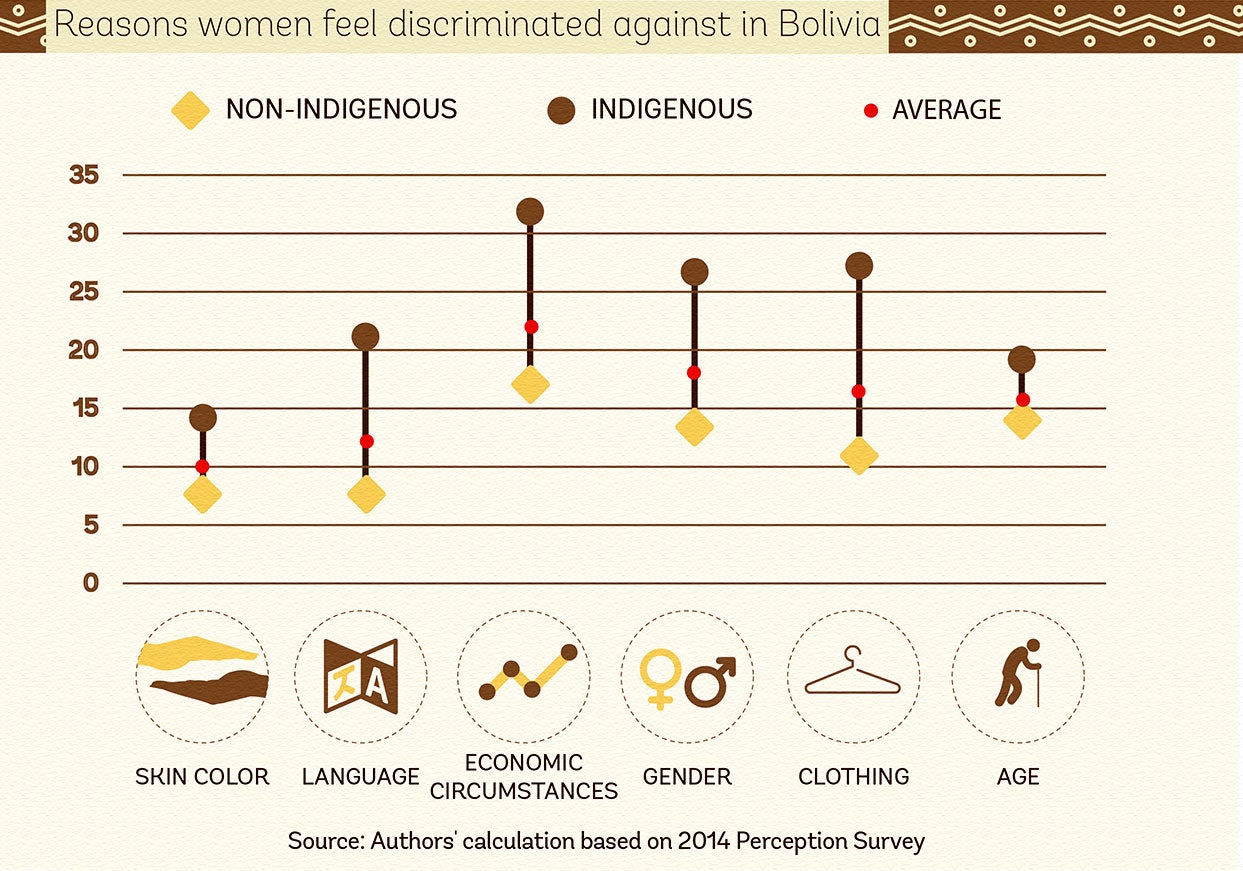

The intersection of gender and ethnicity, for example, can deepen the gaps in some development outcomes. Indigenous Latin America in the Twenty-first Century explains that, while Indigenous Peoples' access to services has improved significantly, services are generally not culturally adapted—so the groups they are meant to benefit do not take full advantage of them. In Bolivia, where more than 40 percent of people identify themselves as Indigenous or Afro-descendants, according to the 2012 Population and Housing Census, indigenous women face a higher risk of being excluded. Further, according to a 2014 Perception Survey on Women’s Exclusion and Discrimination, all women feel discriminated against in different aspects of their lives, with Indigenous women particularly affected.

How does intersectionality and discrimination play out in education and health?

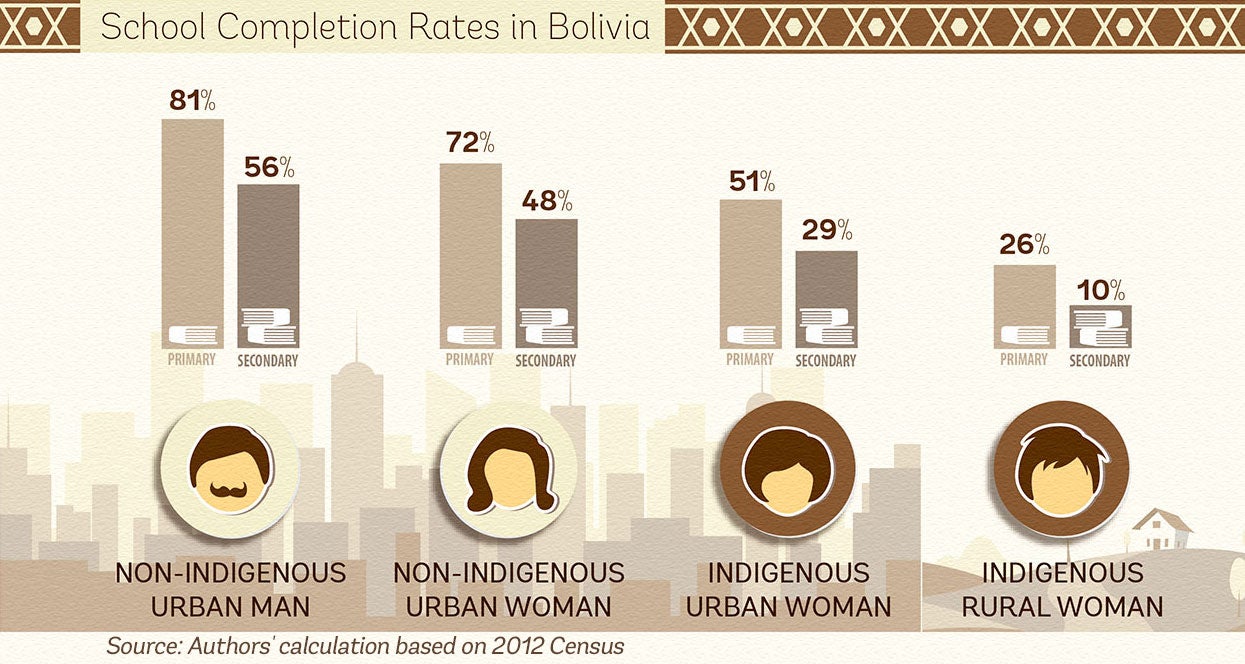

Access to education in Bolivia has improved considerably in recent years. Today, overall primary schooling completion rates and secondary school enrollment rates are similar for boys and girls. Yet major gender gaps persist among Indigenous and rural students.

In urban Bolivia, females are less likely to finish secondary school than males. In urban areas, an Indigenous female student is about half as likely to finish secondary school compared to a non-Indigenous male student. But an Indigenous rural woman is five times less likely than a non-Indigenous urban man to complete secondary school (see graph, based on Census 2012):

Many factors prevent girls from attaining higher levels of schooling in Bolivia, including domestic care work, early pregnancy, and the need for income. But girls who persist in secondary and higher education face other barriers: one in five female students aged 15 to 24 report having experienced discrimination in academic environments: 25 percent of Indigenous women versus 18 percent of non-Indigenous women.

The situation is similar in terms of access to key health services. According to household survey data (2013), while almost all non-Indigenous women in urban Bolivia give birth with either a nurse or a doctor present, that is the case for only 6 out of 10 Indigenous women in rural Bolivia. While this may be explained in part by Indigenous women’s preferences to use traditional parteras, the difference in access rates may also in part be driven by perceived discrimination. According to the Perception Survey, 20 percent of Indigenous women report having experienced discrimination when seeking care, compared to 14 percent among non-Indigenous.

Investments in education and health shape the ability of men and women to reach their full potential, allowing them to take advantage of economic opportunities and lead productive lives. Limited access to these kinds of investments not only adversely affects an individual’s opportunities, but may have significant costs for entire communities and economies.

Inclusion must be front and center on the development agenda. More and better information—both qualitative and quantitative—is needed to highlight the persistent issue of overlapping disadvantages. This will allow us, ultimately, to do much more to expand every person’s capacity to participate fully and equally and achieve his or her potential. As Florina Lopez said earlier this month, "Without the effective participation of Indigenous women in society, it will be difficult to eradicate the poverty and extreme poverty that we live in."

Related Links:

- Data Portal: Bolivia Perception Survey on Women’s Exclusion and Discrimination. This link gives you access to the indicators from the 2014 Perception Survey, coordinated by the Bolivian women’s rights NGO La Coordinadora de la Mujer with support from the World Bank Group’s Umbrella Facility for Gender Equality (UFGE).

- World Bank Group Gender Strategy (FY16-23): Gender Equality, Poverty Reduction and Inclusive Growth

- Bolivia: Challenges and Constraints to Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment

- Voice and Agency: Empowering Women and Girls for Shared Prosperity

- Gender Education Gaps among Indigenous and Nonindigenous Groups in Bolivia

Join the Conversation