Putting in place the funding, systems, and plans before a disaster strikes can help dull the impact of disasters by enabling earlier, faster and more effective response and recovery.

But can we go further, making disasters even ‘duller’ by also releasing finance before a disaster strikes?

UN Under Secretary General for Humanitarian Affairs, Mark Lowcock, recently set out a compelling vision for how the humanitarian system can be improved. He argued that “disasters are predictable… we need to move from today’s approach where we watch disaster and tragedy build, gradually decide to respond, and then mobilise money and organisations to help, to an anticipatory approach, where we plan in advance for the next crises, putting the response plans and money for them before they arrive, and releasing the money and mobilising the response agencies as soon as they are needed…”

These are also the key ingredients for Disaster Risk Finance as set out in the book Dull Disasters, which brings together insights into what works and why in Disaster Risk Finance from a three year long research project by the UK Department for International Development, the World Bank Disaster Risk Financing and Insurance Program, and the Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery (GFDRR).

Disaster Risk Finance is now a well-established toolkit to help Finance Ministers and other financial decision makers deal with shocks more effectively as part of their day to day risk management. And systems for pre-arranged financing are working. Most recently, Tonga received a $3.5 million payout after the impact of Cyclone Gita from the Pacific Catastrophe Risk Insurance Company (PCRIC). Last year, the Caribbean Catastrophe Risk Insurance Facility paid out more than $55 million within 14 days to Caribbean islands hit by the devastating Hurricanes Irma and Maria. While we don’t suggest that early and pre-arranged financing alone can solve the complexities of disaster response, it can create the certainty and predictability required to develop good planning and systems for response and recovery.

But disasters rarely come as a surprise. Many shocks can be seen coming days or even months ahead, but generally the finance necessary to act doesn’t flow until much later. In a particularly tragic example, in 2011 international humanitarian aid to Somalia came months after forecasts first predicted a major food security crisis, leaving millions without food.

Can we tackle this by designing systems that release some funding based on a forecast of a coming shock, to kick-start preparations early? And could this be applied at scale in national systems and in humanitarian financing flows?

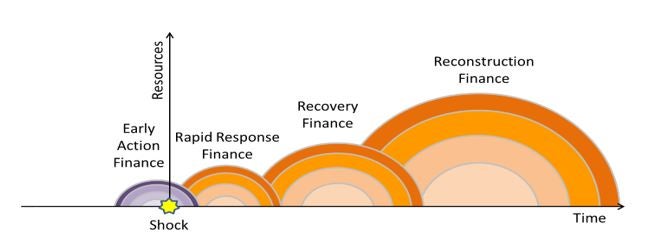

This can be represented in a graph showing financing needs at different stages of an emergency.

The Red Cross Red Crescent Climate Centre, in collaboration with national societies around the world, has led pilots on forecast based financing at the community level. For example, this past September, the Togolese Red Cross distributed emergency-shelter items which allowed 100 households to temporarily relocate to elevated highways as their homes were threatened by raising water-levels. Supported by the German government and the German Red Cross, this project builds on a new low cost approach to flood risk forecasting including crowd sourced data, developed with the support of GFDRR’s Code for Resilience initiative.

Donors, UN Agencies, the IFRC and NGOs are already exploring how to scale up these approaches within their own humanitarian systems and looking for innovative financing to backstop early action. In late 2016, the START network launched its “ Anticipation Window” to put this into action. A lesson from these initiatives is that risk financing is about much more than just the money. It is about having pre-agreed triggers for action, plans, and systems in place before a disaster strikes to ensure that finance quickly and effectively reaches those people that need assistance.

Scaling from community pilots to national programming

Disaster Risk Finance is an evolving policy area. Better financing for earlier action should only require small adjustments to ongoing work. This includes developing standard operating procedures that identify actions and triggers in advance, and prepositioned financing – the same ingredients for ‘Dull Disasters’.

We will look further into this as part of a growing collaboration between DFID and the World Bank’s Disaster Risk Financing and Insurance Program through the new Centre for Global Disaster Protection. Immediate next steps include a DFID funded research project that aims to identify the key constraints and opportunities to take forecast-based early action to scale, a new window of the DFID-GFDRR Challenge Fund on innovation in financing early action, and the possibility to pilot promising approaches through new partnerships of the Centre for Global Disaster Protection and the World Bank. Join us also in conversations on this at the Commonwealth Heads of Governments Summit next week in London and the 2018 Understanding Risk Forum in May in Mexico.

We look forward to hearing from potential partners.

Join the Conversation