It should be celebration time for public-private partnerships and other forms of private investment in infrastructure. The pent-up demand for infrastructure in the developing world has never been greater—over double the $900 billion per year being spent now, according to our rough estimates; and governments around the world are falling over themselves to show donors, strategic investors and creditors alike how committed they are to attracting private investment to infrastructure.

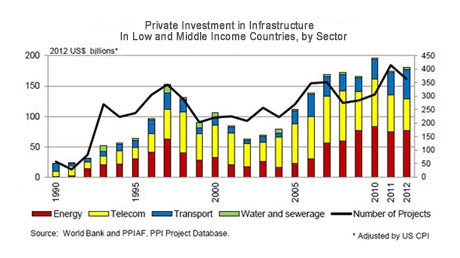

Somehow, as we release the 2012 data on private participation in infrastructure (PPI) across the developing world [see: PPI Database], I just can’t get myself to pop the champagne. True, the march into higher levels of investment, uneven as it is, continues. Commitments for PPI totaled $182 billion in 2012 and most developing countries clocked in with at least one private investment. But the total is still less than 20 percent of what the developing world is spending on infrastructure, and less than 10 percent of what is needed to reach growth targets. It is still less than one percent of GDP for developing countries.

Somehow, as we release the 2012 data on private participation in infrastructure (PPI) across the developing world [see: PPI Database], I just can’t get myself to pop the champagne. True, the march into higher levels of investment, uneven as it is, continues. Commitments for PPI totaled $182 billion in 2012 and most developing countries clocked in with at least one private investment. But the total is still less than 20 percent of what the developing world is spending on infrastructure, and less than 10 percent of what is needed to reach growth targets. It is still less than one percent of GDP for developing countries.

If the demand is out there, what are all those investors scared of?

During a recent roundtable with investment banks and equity investors in Singapore, it became clear about halfway through the open discussion that most everyone in the room was chasing the same dozen projects.

“Pipeline!” we concluded. Governments need more assistance in preparing projects and undertaking rigorous feasibility studies so that there is a line of bankable projects awaiting investment.

“Consistency!” we concluded. Standardizing contracts and concessions, fuel and power purchase agreements and bidding documents will mean that every transaction doesn’t feel like financiers and investors are being asked to convert to a new religion.

“Sector health!” we concluded. In too many cases, the underlying economics of cost recovery aren’t there. Since investors only help finance infrastructure, not pay for it, the sectors need to have reliable cash flow to attract PPI.

“Instruments!” we concluded. If we could reinvigorate project bonds and introduce them to developing country infrastructure to cover construction risk, perhaps we could tap that elusive pot of gold known as “pension funds” and other institutional investors looking for a stable long-term investment without that early development and demand risk.

“Liquidity!” we concluded. If maturities were longer and costs of capital lower, then a lot of projects would be financially viable. Who could afford a house in Washington, DC, let alone a power plant in Burundi, with a five-year mortgage?

Like a trick question on a standardized test, the correct answer may be, “All of the Above.” But those were the gaps that were easiest to name. There is yet another shadow over the investment environment. This is sovereign risk, which sits between demand-side failures—project bankability and sectoral economics, and supply-side failures, like the dearth of long-term liquidity.

Recent empirical work relating country-level risk to levels of PPI shows just how important sovereign risk is to infrastructure investment [see: “Effects of Country Risk and Conflict on Infrastructure PPP”] In fact, the work suggests that country risk ratings are a reliable predictor of the likelihood of investment in PPPs as well as the level of investment. Foreign Direct Investment overall is not nearly as sensitive to sovereign risk as PPI. This suggests that other big investors in developing economies—mining, oil, gas, or the garment industry—are able to attract returns commensurate with the risks they are assuming. Not so for infrastructure sectors—especially when mobile telephony is removed from the data.

To assign an average value, an improvement in country risk ratings by one standard deviation is associated with a 27 percent higher chance of having a PPP commitment, and a 41 percent higher level of investment in dollar terms. Country risk is a good predictor for both greenfield investments and concession and for all sectors—though particularly for energy investments.

So, as we help our clients embark on a drive to increase the leverage of public funds and to grow private investment—to close that infrastructure financing gap—we’ll need a multi-pronged approach. Build that pipeline, put the sectors on solid economic ground, bring in the liquidity and the right financial instruments, but, let’s not forget the country context. It too is driving investments.

What more evidence do we need for an approach to development that marries technical expertise with country context?

Join the Conversation