Technology and what it will do to change how we work is the driving obsession of the moment. The truth is that nobody knows for sure what will happen – the only certainty is uncertainty. How then should we plan for the jobs that don’t yet exist?

Our starting point is to deal with what we know – and the biggest challenge that the future of work faces – and has faced for decades – is the vast numbers of people who live day to day on casual labor, not knowing from one week to the next if they will have a job and unable to plan ahead, let alone months rather than years, for their children’s prosperity. We call this the informal economy – and as with so much pseudo-technical language which erects barriers, the phrase fails to convey the abject state of purgatory to which it condemns millions of workers and their families around the world.

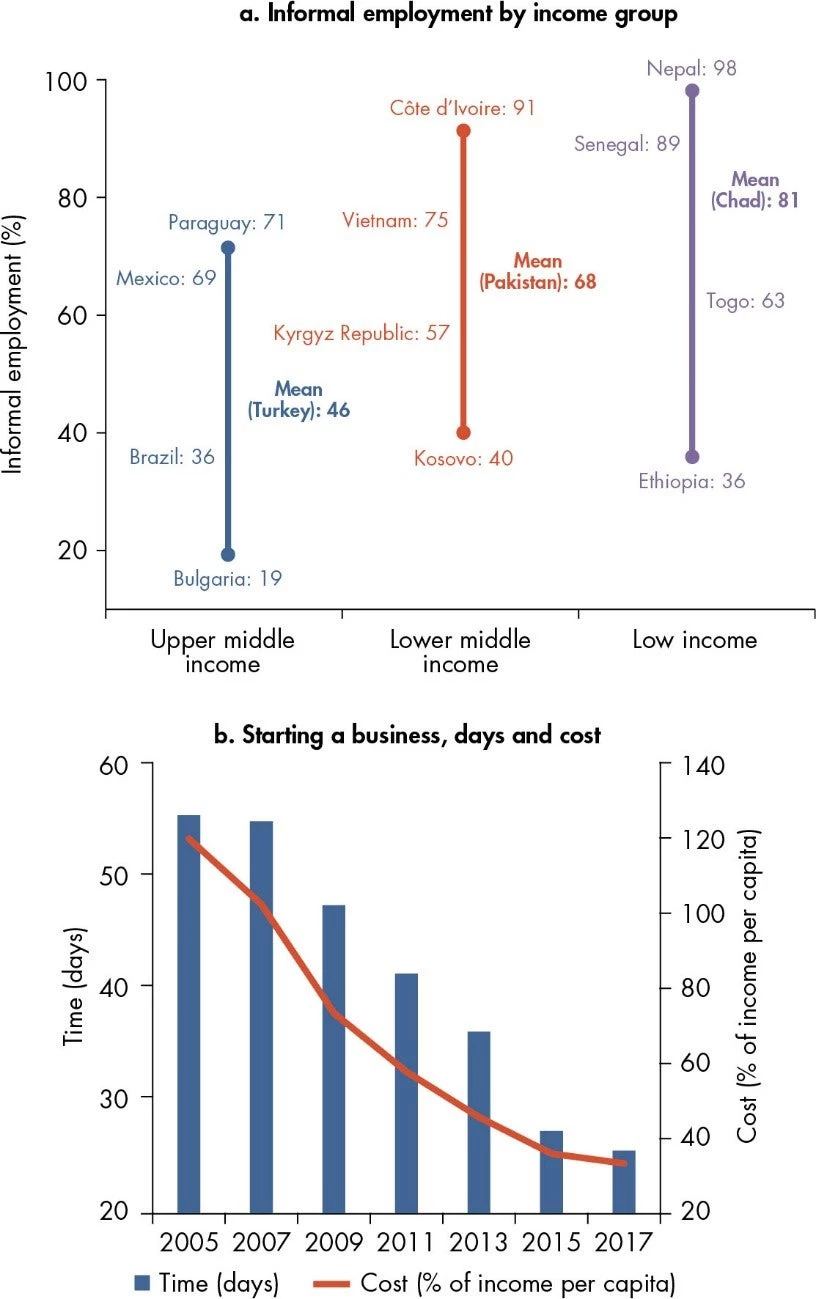

A worker is informally employed when she does not have a contract, social security, health insurance or any other protections. Informal work is a means of survival, nothing more. From the rickshaw pullers in the streets of Dhaka to the mobile fruit vendors of Nairobi, the informal economy is omnipresent. Informal employment is more than 70 percent in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, and more than 50 percent in Latin America. In Cote d’Ivoire and Nepal, it is more than 90 percent. As you can see in the graph below, which I have borrowed from the draft World Development Report 2019, informal work is more widespread for low income than high income economies.

In spite of improvements in the business environment, informality remains high. Since 1999, India has seen its IT sector boom, become a nuclear power, broken the world record for the number of satellites launched in a single rocket and achieved an annual growth rate of nearly 6 percent. Yet, the size of its informal sector, by some estimates, has remained around 90 percent. In Sub-Saharan Africa informality remained around 75 percent between 2000-2016. In South Asia, it has increased from an average of 50 percent in the 2000s to 60 percent between 2010-2016.

Most informal workers tend to be engaged in low productivity activities, with little skill development and almost zero growth prospects. In India, a year of work in the formal sector doubles wages compared with a year of informal work. In Kenya the picture is similar. The difference is potent. Informal businesses are the business of the poor. The small scale of their endeavors reduces the chances of moving out of poverty.

So, what can we do about it? Clearly there is no one-size-fits-all solution – but the answer involves a mixture, depending on the context, of improvements to the business environment, human capital investments and the promise of technology, which is so current in discourse.

Technology can reduce informality. Peru succeeded in creating 276,000 new formal jobs by the introduction of e-payroll - an electronic procedure through which employers send monthly reports to the National Tax Authority. The reports cover information on workers, pensioners, service providers, personnel in training, outsourced workers and claimants.

Investment in human capital helps. When young people are equipped with the right skills, they are more likely to obtain a formal job than an informal one.

You can learn more about how technology helps people stuck in dead-end jobs by reading the draft of the World Bank’s World Development Report 2019.

Of course, the report doesn’t have all the solutions but, in a world with so much uncertainty, what it sets out is a way to think about the challenges ahead. Technology isn’t the only answer to many of the problems we face but by properly framing the right questions now there is a better chance that it will help more than hinder our progress.

Join the Conversation