Photo credit: Shutterstock

Photo credit: Shutterstock

The worst global food crisis in a decade was one of the top issues discussed at the 12th ministerial meeting of the World Trade Organization last month . It is a crisis made worse by the growing number of countries that are banning or restricting exports of wheat and other commodities in a misguided attempt to put a lid on soaring domestic prices. These actions are counterproductive—they must be halted and reversed.

The price of wheat, a key staple in many developing countries, has shot up by 34 percent since the Russian invasion of Ukraine in late February. Other food costs have also risen. In response, as of early June, 34 countries had imposed restrictions on exports on food and fertilizers – a figure approaching the 36 countries that used such controls during the food crisis of 2008-2012.

These actions are self-defeating because they reduce global supply, driving food prices even higher. Other countries respond by imposing restrictions of their own, fueling an escalating cycle of trade actions that have a multiplier effect on prices.

Everyone is squeezed by food price inflation, but the poor are the hardest hit, especially in developing countries, where food accounts for half of a typical family’s budget. Moreover, developing countries are especially vulnerable because they tend to be net importers of food. History leaves no doubt about what happens when food becomes scarce or unaffordable for the poorest people: the 2008 food crisis, for example, brought on a significant increase in malnutrition, particularly among children. Some studies showed school drop-out rates of as much as 50 percent among children from the poorest households.

Actions to limit exports had a significant effect on food prices in the 2008 crisis, making matters worse. Research shows that if exporters had refrained from imposing restrictions, prices on average would have been 13 percent lower.

This time, the war in Ukraine is accelerating a price surge that started earlier as a result of unfavorable weather in key producing countries, the rapid economic recovery after the COVID-19 induced slump, and the growing costs of energy and fertilizers. The war has severely disrupted shipments from Ukraine, one of the world’s largest food suppliers . The country is also a major supplier of corn, barley, and sunflower seeds, which are used to make cooking oil – goods that can’t reach world markets because Ukraine’s ports are blockaded .

The multiplier effect, whereby unilateral trade restrictions fuel additional policy activism and higher prices, is already visible. In March, Russia, the world’s No. 2 exporter of wheat with a 17.5 percent share by volume, announced a temporary ban on exports of wheat and other grains. It was followed by smaller exporters such as Kazakhstan and Türkiye. As of early June, 22 countries had imposed restrictions on wheat exports, covering 21 percent of world trade in the grain. These restrictions led to a 9 percent increase in the price of wheat – about one seventh of the total increase in prices since the beginning of the war.

Export restrictions aren’t the only trade measures governments are undertaking in response to higher prices. Some countries are cutting duties or otherwise easing restrictions on imports. Chile, for example, increased discounts on customs duties on wheat. Ordinarily, permanently cutting import restrictions would be welcomed. But in a crisis, temporary reductions in import restrictions put upward pressure on food prices by boosting demand, just as export restrictions do in cutting supply.

Among the hardest hit by trade restrictions are developing economies in Africa, Asia, Latin America, and the Middle East. Bangladesh imports 41 percent of the wheat it consumers from the Black Sea region. For the Republic of Congo, the figure is 67 percent, and it is 86 percent for Lebanon. Given the extent of the dependence, immediate pain is likely for the people of these countries, because alternative suppliers will not be available in the near term. Rising prices will eventually create incentives for major agricultural exporters to expand production and replace some of the exports from the Black Sea region, but that will take time.

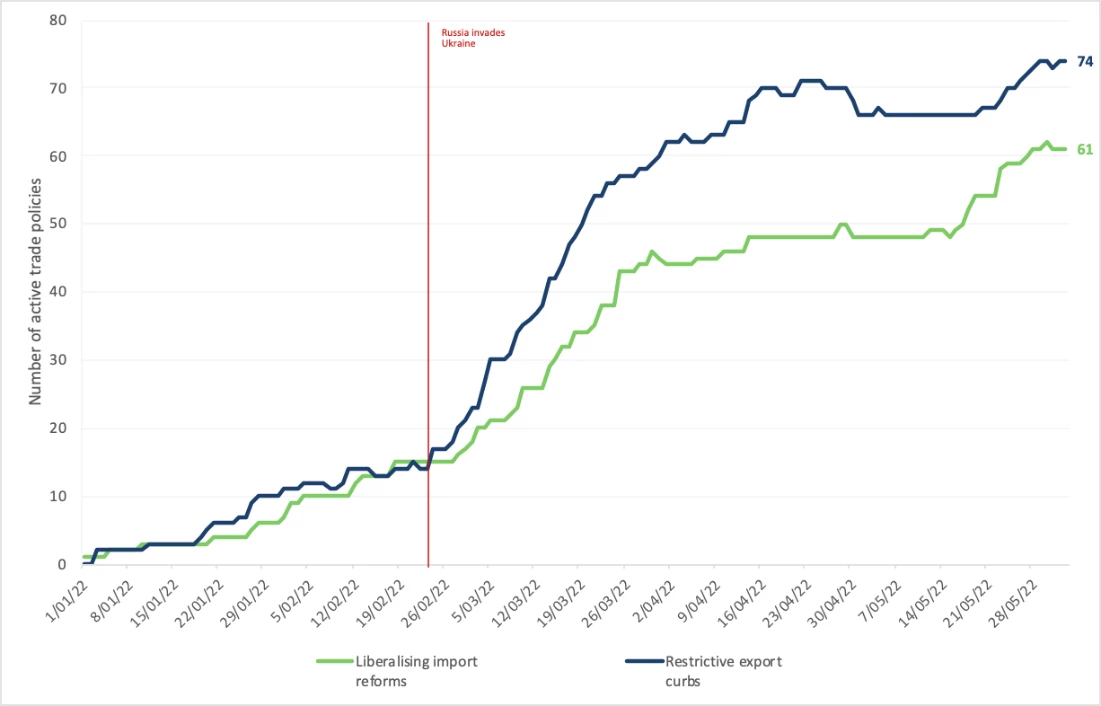

All told, monitoring by the World Bank Global Trade Alert suggests 74 export curbs such as taxes or outright bans have been announced or imposed on fertilizer, wheat, and other food products since the beginning of the year (98 counting the ones that have lapsed). Similarly, 61 liberalizing import reforms such as tariff cuts have been counted (70 considering the ones that have lapsed).

Number of active trade policies on food and fertilizers—January 1 to June 2, 2022

Source: Bank staff calculations using World Bank and Global Trade Alert trade policy monitoring in essential goods.

At the conclusion of their meeting, representatives from more than 100 WTO member countries took an important first step: they agreed to step up their efforts to facilitate trade in food and agriculture products, including cereals and fertilizers , and they reaffirmed the importance of refraining from export restrictions.

In addition, the Group of Seven advanced economies—which includes major food exporters like Canada, the European Union, and the United States—has already pledged to avoid export bans and other trade-restrictive measures. World Bank President David Malpass has called on other major food exporters to join in that promise. Together, these countries represent over 50 percent of global exports of staples like wheat, barley and corn.

This is a matter of urgency: to defuse the food crisis, it’s imperative that all food-related trade restrictions imposed since the start of the year be lifted as swiftly as possible. The war in Ukraine has created needless suffering for the most vulnerable people everywhere. The global community has a duty to cooperate fully to expand the flow of food across the world —so the misery of hunger is not added to the mix.

Join the Conversation