As a young scientist, I travelled to the Brazilian Amazon to research forest fires. After weeks of talking to rural producers, rubber tappers, indigenous peoples and cattle ranchers, I realized that I had to think beyond conservation science and climate change implications to understand the Amazonian landscape. The nexus between people and the rainforest was also important. I came away wanting to help ensure that the value of forests to people, and the value of people to forests remained closely linked and well-recognized.

The loss of biodiversity—which is driven by rapid conversion of habitats and landscapes, the depletion of ocean fisheries, and climate change—is not new. But concern for how to decrease the loss of biodiversity is. We are no longer just scientists and conservationists. The international community now makes the loss of biodiversity central to the global political debate: nations have the responsibility to protect natural assets.

Since its inception during the Rio Earth Summit in 1992, the Convention on Biological Diversity has empowered nations on this critical path; that is to make commitments on (a) conserving species, (b) using biological diversity sustainably, and (c) promoting sustainable development. To further raise awareness and understanding, the UN made May 22nd the International Day for Biological Diversity.

This year we celebrate the day by focusing on mainstreaming biodiversity so that we may recognize its role in sustaining people and livelihoods. Ethics and aesthetics are reasons we should preserve species and ecosystems. However, unless we see biodiversity as an asset for shared benefits and social development, governments will resist biodiversity commitments—especially when confronted with the false dichotomy between protecting the

environment and fighting poverty.

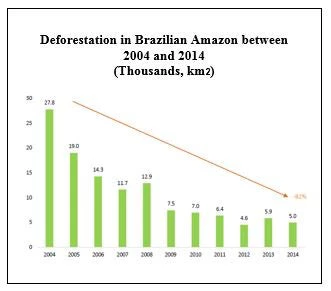

Conservation with development can positively impact biodiversity. For instance, throughout the Amazon, the land and social justice claims of communities in rubber tappers’ organizations coalesced with environmental concerns over alarming deforestation rates. This led to the concept of “extractive reserves” or sustainable use areas, as a way to guarantee people’s rights while preserving large tracts of forests. Now, more than 20 years later, the Brazilian Amazon has more than 540,000 sq km of sustainable use areas, directly benefiting and providing livelihoods for over 150,000 people. In fact, the second generation of these polices, have quashed deforestation. The net deforestation rate declined by 82%-- from around 27,000 km2 in 2004 to less than 5,000 km2 by 2014, preventing 3.2 billion tons of carbon dioxide emissions, which is equivalent to how much the US would save by taking all the cars off its roads for three years. This is a real game changer.

Protecting biodiversity beyond protected areas

Protected areas are key to safeguarding natural habitats for plant and animal diversity. However, they keep people out. Without local communities, conservation loses momentum and political will. The need to look beyond protected areas and take concrete steps for the sustainable use of biodiversity in broader landscapes and seascapes is urgent. Especially as we face the challenges of food production, natural resource use, modification of landscapes, and climate change.

The debate and actions over strategies that reconcile food production, biodiversity conservation and ecosystem services have focused on two alternatives: land sharing and land sparing. This debate has neglected Indigenous Communities, traditional extractivist communities and family farmers, who survive on the income from subsistence farming and harvesting of biodiversity products, fishing and hunting. About 1.3 billion people in rural areas—or 20% of the global population-- depend on forests and trees on farms for their livelihoods. Around 300-350 million people--half of whom are indigenous-- live close to dense forests and depend almost entirely on forest biodiversity for subsistence. Involving people in protecting forest biodiversity ensures long term conservation and sustainable development.

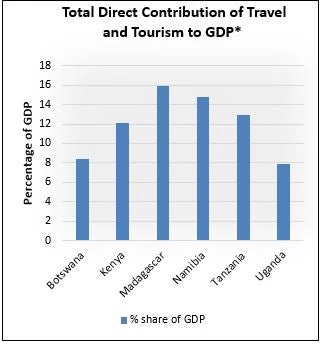

Since much of the best remaining wildlife areas are poorly suited for alternative uses such as agriculture, the Bank is helping several African countries realize the potential of nature based tourism using a three-pronged approach:

Protecting natural assets, growing the business to ensure that nature based tourism remains attractive to government and private sector long term plans and sharing the benefits so that employment opportunities and revenue-sharing arrangements reduce the cost of living with wildlife and support local communities.

As we celebrate the International Day for Biodiversity this Sunday, I look back at the last 20 years that I have spent working in the Brazilian Amazon, captivated by its people and biodiversity. I am committed as ever to doing the best I can to conserve diversity of all life forms. The mission continues.

(*World Bank Staff calculations based on World Travel and Tourism Council data).

Join the Conversation