Starting this weekend, Stockholm will host the largest annual congregation of water aficionados, during World Water Week 2016. It is an opportune moment to reflect on what social inclusion means for water , and on three stylized myths in the “mainstream” discourse, although there are also influential social movements that present alternative views.

Myth 1

Inclusion in water is about poverty or being “pro-poor”? Social inclusion may be about the poor but it needn’t necessarily be so.

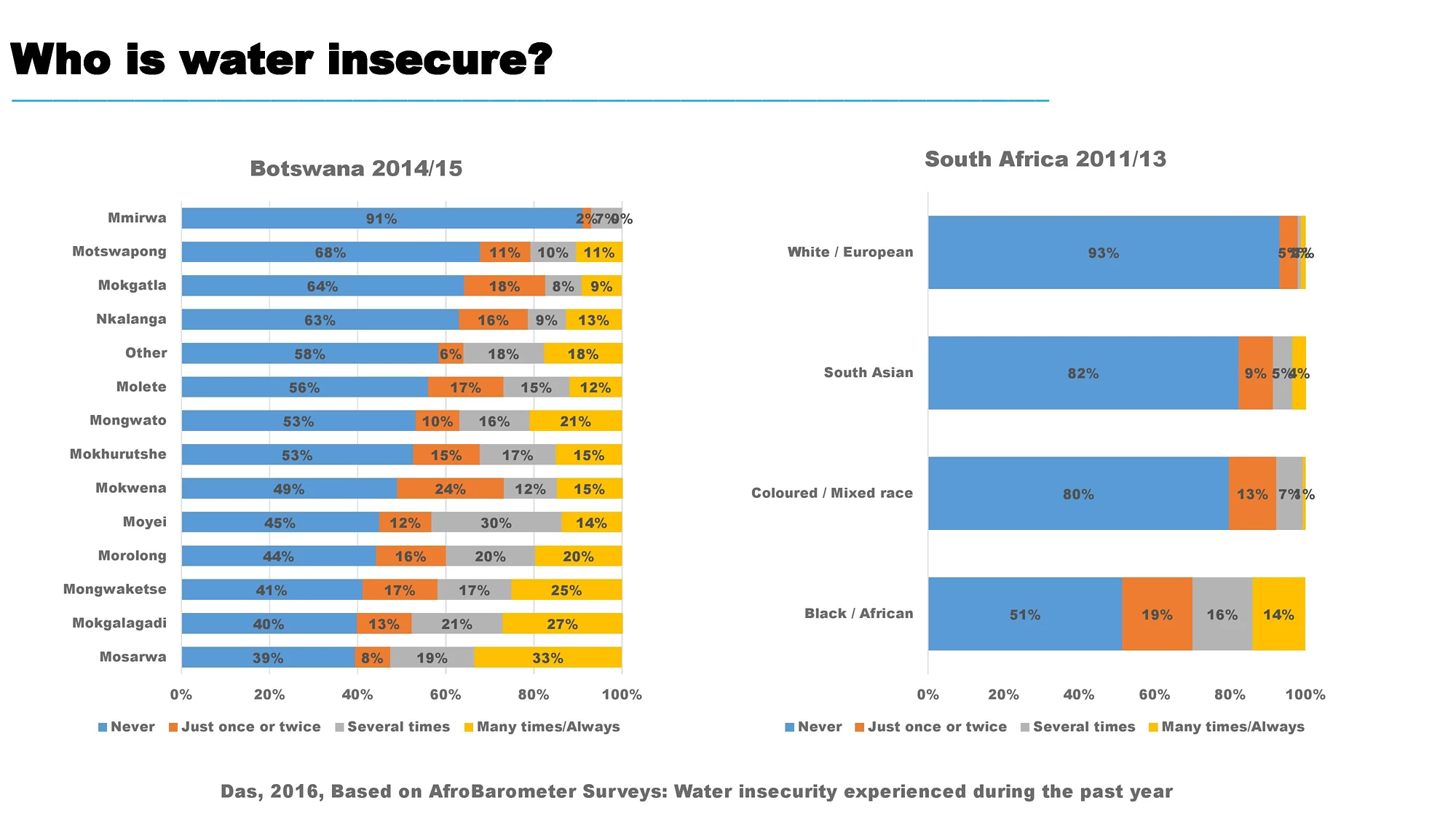

Take a look at the graphs we’ve generated from the AfroBarometer surveys. It is clear that water insecurity isn’t just about poverty. In the same country, some people are almost never water-insecure, while others, depending on their race or ethnicity are much more likely to be so. There is clear misallocation of water resources. Many would argue that this is a function of location, and it often is, but why are some groups systematically located in hard-to-reach areas or over-represented among the poor?

The empirical literature is rich on allocative efficiency in water, but not as rich on allocative equity or on the potential trade-offs, unless such tradeoffs are thought of in terms of pricing of services.There are notable exceptions, however, and social movements have historically forced difficult conversations. At the World Bank, we say: social inclusion is also about shared prosperity.

Myth 2

Inclusion is about gender? This is a somewhat gross reductionism (especially when it reduces gender to women!). Women are half the world’s population (in most countries). Not all are disadvantaged in every domain! It is a problematic reductionism in yet another way; it implicitly reduces women to being vulnerable when in fact, like other groups, they are also agents of change.

Social inclusion is about individuals and groups who are disadvantaged or excluded because of their identity. They could have disabilities or belong to indigenous groups, or to religious, caste, ethnic or sexual minorities. Or to a mix of these. Nobody is just a woman; they are a woman who may belong to a particular ethnic group and depending on their place in the life-cycle, may be either advantaged or disadvantaged.This understanding of intersectionality adds nuance to the discussion of identity and exclusion, where gender is one, albeit salient aspect. Such understanding is also central to the way we think about policy and programs.

Myth 3

Inclusion is about access to services? We seldom see issues of water resources being viewed through the lens of inclusion in the “mainstream” discourse (although this may be a bit of a generalization). Yet, there are knotty questions. Who owns water resources? Who decides what to do with them? What’s the relationship between natural resources and service provision? These questions take us into the political realm which can make technocrats uncomfortable and hence, sometimes dismissive. They also force follow-on questions like why some groups have greater control over water resources. In a report from 2011 we argued that poor access to services for Adivasis in India are a symptom of their poor control over natural resources, in turn stymieing voice and power. Real inclusion is only possible we, as policy advisers and policymakers transcend the artificial dichotomy between resources and services.

All this to say that social inclusion is the road to social sustainability, in the water sector and beyond. On Wednesday in Stockholm, a Davos style panel will discuss the relationship between social inclusion and social sustainability. What are the barriers to social sustainability and on the flip side, what deepens it? How can we collectively promote social inclusion in the road to sustainability?

Join the session at 11am CET and tweet me @DasMaitreyi.

Join the Conversation