Photo credit: World Bank

Almost 600 million Indians living in rural areas defecate in the open . To meet the ambitious targets of the Indian government’s Swachh Bharat Mission Grameen (SBM (G)) – the rural clean India mission – plans to eliminate open defecation by 2019. SBM (G) is time-bound with a stronger results orientation, targeting the monitoring of both outputs (access to sanitation) and outcomes (usage). There is also a stronger focus on behavior change interventions and states have been accorded greater flexibility to adopt their own delivery mechanisms.

The World Bank has provided India with a US$1.5 billion loan and embarked on a technical assistance program to support the strengthening of SBM-G program delivery institutions at the national level, and in select states in planning, implementing and monitoring of the program.

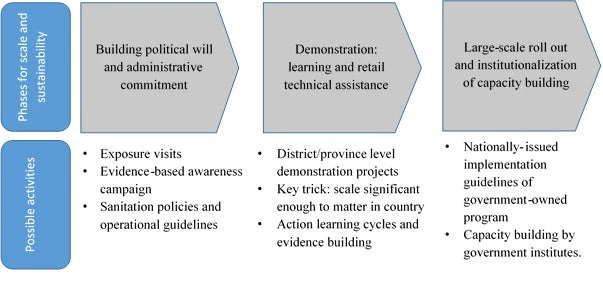

1. Further increasing political will and administrative commitment by identifying and creating local sanitation champions at the district level – for example, through exposure visits and evidence-based advocacy – and addressing key institutional bottlenecks such by supporting the state to formulate a state-specific sanitation policy.

2. Providing technical support to selected districts to demonstrate that sanitation can be delivered at the scale of a district and in a sustainable manner, and to develop district-wide approaches that are tailored to a particular state.

3. Supporting the strengthening of state governments’ institutional capacity to roll out the successful models to other districts, eventually covering the entire state.

The study covered WSP’s work in eight states (Bihar, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Meghalaya, and Rajasthan) between 2002 and 2013. This saw varying levels of success, with the experience in Rajasthan proving particularly pertinent in informing the three-step pathway.

As well as the creation of local champions, and government decision makers being willing to try something new, success factors included the ability to demonstrate progress by starting work in locations that were not the poorest, so households had some resources to invest in sanitation; and the sanitation sector in the state not being fragmented among multiple development actors. Further details about what we learned can be found in the newly-published learning note.

| Rajasthan - the three-step pathway in action A large and mostly rural state, Rajasthan has historically lagged behind other states in sanitation: only 19.6 percent of rural households had a toilet in 2011. We invited ten of the state’s 32 district collectors – high-ranking officials, who are often relatively young and ambitious – on a study visit to Himachal Pradesh, which is much further advanced in rolling out sanitation. During that visit, we observed that three of the ten collectors seemed especially enthused. We supported them to improve sanitation in their districts and showcased their successful experiences to the state government. The Chief Minister of Rajasthan declared sanitation as one of the state’s top development priorities, with a target of eliminating open defecation by 2018. We gave the state government the technical assistance it needed to set out clear policies and guidelines and strengthen the responsible institutions: making processes more efficient, improving communications between state and district administrations, and reducing delays in implementation. |

Join the Conversation