World Bank staff, including Vice Presidents, Global Directors, Country Director, showing support for better menstrual health and hygiene for all women and girls

World Bank staff, including Vice Presidents, Global Directors, Country Director, showing support for better menstrual health and hygiene for all women and girls

If menstrual health and hygiene (MHH) is well managed from the start, it has a surprisingly high potential to contribute to increasing female empowerment at a critical stage of a girls’ life. Getting this right is important. We can see the consequences of failing to do so:

- Infrastructure: At least 367 million children have no sanitation services in their schools, and women and girls globally lack adequate facilities to manage their menstruation.[1]

- Education: This lack of infrastructure and stigma contributes to absenteeism; in one Kenyan study 95% of menstruating girls missed 1-3 school days, 70% reported a negative impact on their grades, and over 50% stated falling behind in school due to menstruation.

- Product Supply/Affordability: Even where the infrastructure is adequate, in many countries there is a lack of affordable menstrual products or gaps in supply. Among the 355 million menstruators in India, 12% cannot afford period products, and that percentage spikes to 65% in Kenya.[2] Menstrual products also have an impact on sexual reproductive health in other critical ways; for example, a randomized control trial (RCT) in Kenya found that 10% of girls age 15 self-reported having transactional sex to obtain sanitary pads (out of a study of 9,000 girls).[3]

- Solid Waste/Environment: And where there are menstrual products, they are often not sustainable; with 40 billion disposable pads soiled every month, sanitary products contribute to increasing global waste.[4] In India alone, 12.3 billion pads per month generate 113,000 metric tons of annual menstrual waste.[5]

- Stigma: Social norms and stigmas set off an early pattern of linking something that defines one biologically as a woman, menstruation, as being dirty and shameful. More than 80% of adolescent girls in rural India believed that menstrual blood contained harmful substances and close to 60% believed it should not be talked about openly.

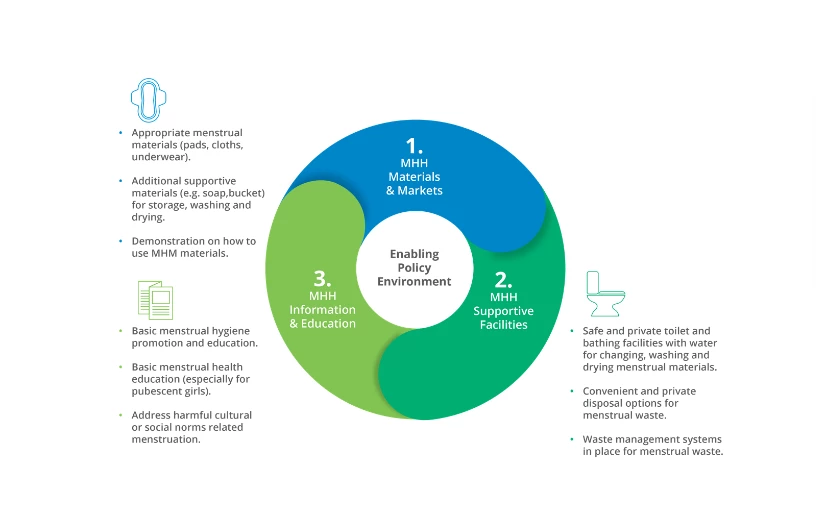

Not only do the impacts cut across sectors – evidence shows that the solutions most likely to reduce school drop-out rates and enhance female empowerment are those that combine Sexual and Reproductive Health Education, with appropriate sanitary infrastructure, and the availability of sustainable and affordable menstrual products, in an enabling policy environment. Within the World Bank, a multi-sectoral MHH Working Group comprising the Water GP (Global Practice), Gender Group, Education GP, Global Financing Facility, Finance Competitiveness and Innovation GP, and Health GP, came together to learn from academia, external partners and entrepreneurs how to advance these types of holistic approaches to MHH in World Bank operations.

For example, one study showed that the provision of menstrual cups reduced adolescent girls drop-out rates from 4% to 1%, decreased B. vaginosis by 41% compared to the control, and reduced (self-reported) transactional sex (noting that a majority of teenage drop-outs are pregnancy related).[6]

In addition, as a multi-billion dollar industry, menstrual products not only provide important entry points for the generation of female employment, but also for providing messaging and links to hotlines and counseling for reproductive health, gender based violence prevention, and reducing stigma, as one entrepreneur in East Africa (Nia, Zana Africa) did. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the entrepreneur reported an uptick in the use of these referral hotlines.

The integration of Sexual and Reproductive Health Education with the provision of sanitary infrastructure that offers privacy, water, soap for handwashing, and appropriate waste bins together with menstrual products can boost adolescent girls’ confidence and reduce drop-out rates. And completion of school increases girls’ earnings and formal employment and overall gross national product (GNP) –Kenya’s GNP, for example, would grow by 3.2 billion a year if all girls were to graduate from school.[7]

An outcome of this process is the MHH Resource Package for water and sanitation professionals, published on Menstrual Hygiene Day today, to bring together available knowledge on effective approaches to designing MHH (almost half of World Bank-supported water supply and sanitation lending projects approved last year included support for MHH, and education and health projects are similarly increasing efforts ).

We are already seeing tangible impact of this approach. In Mozambique, as part of the Urban Sanitation Project and COVID-19 support, the World Bank is financing a set of interventions aimed at ensuring safe return to school. The interventions include water, sanitation, and hygiene facilities in 165 schools, benefiting 157,000 students. But they go beyond infrastructure to include sanitary pads, soap as well as menstrual education.

And here is the good news: in recent interviews conducted with school-aged old girls benefitting from this project, they noted how this has changed their menses – from something that kept them out of school because of embarrassment, fear of teasing, and lack of menstrual products to something they can now manage safely and confidently in school during this very difficult pandemic year.

[1] For 2019; https://washdata.org/sites/default/files/2020-08/jmp-2020-wash-schools.pdf . In 2019, 43%o of schools had either limited (access to water, but no soap) or no hygiene facilities on premises.

[2] See Opportunities International Australia. “Everything You Need to Know About Period Poverty.” (May 27, 2020).

[3] Eijk, Anna Maria van, Kayla F. Laserson, Elizabeth Nyothach, Kelvin Oruko, Jackton Omoto, Linda Mason, Kelly Alexander, et al. “Use of Menstrual Cups among School Girls: Longitudinal Observations Nested in a Randomised Controlled Feasibility Study in Rural Western Kenya.” Reproductive Health 15, no. 1 (December 2018): 139.

[4] Eijk, Anna Maria van, Garazi Zulaika, Madeline Lenchner, Linda Mason, Muthusamy Sivakami, Elizabeth Nyothach, Holger Unger, Kayla Laserson, and Penelope A Phillips-Howard. “Menstrual Cup Use, Leakage, Acceptability, Safety, and Availability: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” The Lancet Public Health 4, no. 8 (August 2019): e376–93.

[5] Management of Menstrual Waste. http://www.path.org/publications/files/ ID_mhm_mens_waste_man.pdf

[6] Source: Phillip- Howard Presentation, 2020 (van Eijk et al Reproductive Health; 15:139, 2018; Juma et al BMJ Open; 0:e015429, 2017; Phillips-Howard et al BMJ Open; 6(11):e013229. 2016; Mason et al Waterlines; 34:1, 2015 Benshaul-Tolonen A et al, CDEP-CGEC Working Paper No 74, 2019; Babagoli MA, Benshaul-Tolonen A, et al. CDEP‐CGEG Working Paper No 87, 2020)

[7] Chaaban, Jad, and Wendy Cunningham. Measuring the Economic Gain of Investing in Girls: The Girl Effect Dividend. Policy Research Working Papers. The World Bank, 2011.

Join the Conversation