Co-authors:

International Water Management Institute – Christopher Patacsil

Keystroke Communications – Paul Stapleton

Private sector investment principles could make the fecal sludge management chain sustainable, says a new report released in time for FSM4

To understand why innovation in fecal sludge management matters, ask yourself this: In 15 years, when almost 5 billion people are using on-site sanitation, solutions like pit latrines and septic tanks, what will the world do with all the fecal waste? About half that many people use onsite sanitation today, and we already have a hard time keeping up.

Today, global leaders will convene at the 4th International Fecal Sludge Management Conference (FSM4) to discuss this very issue. Government, nonprofit, and industry leaders will explore recent learnings, solutions, and recommendations that prioritize the safe and effective management of fecal sludge as a key component of sanitation service delivery.

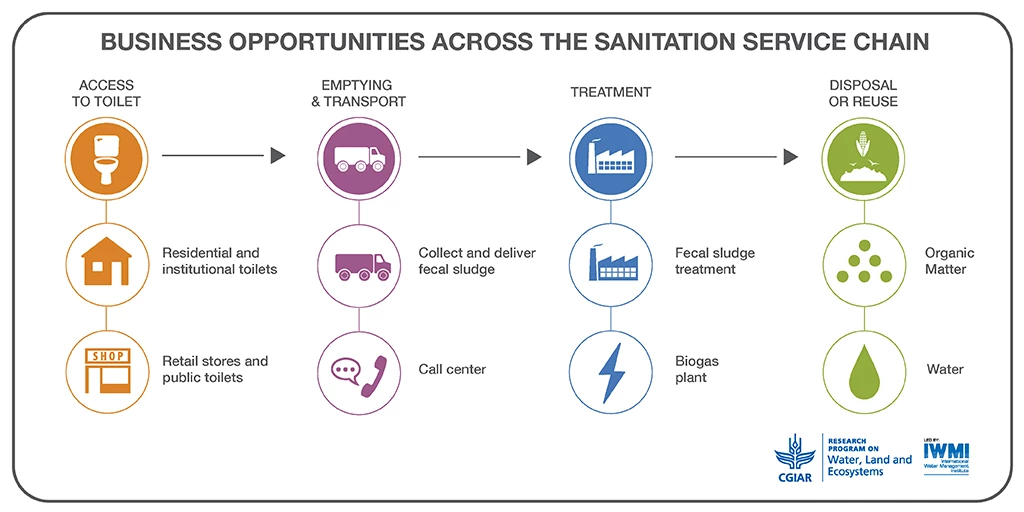

The “business as usual” approach to fecal sludge management is based on subsidies. However, with a steadily growing user base, and limited resources from local governments, subsidies won’t be enough. A diversity of cross-sector approaches will be necessary, including those that treat waste management as a profitable business opportunity.

A new report from the CGIAR Research Program on Water, Land, and Ecosystems by researchers from the International Water Management Institute lays out the value in taking this approach. According to the report, investors and entrepreneurs can find the best set-up for sustainable service delivery , including cost recovery in a particular location and context, by determining the feasibility of each business model.

Based on the analysis of 44 fecal sludge management cases from Asia, Africa, and Latin America, the report presents a variety of business models for managing fecal sludge across the full sanitation value chain. Which model works best depends on the context.

To select and implement the best business models for a particular context, there are three necessary steps:

- A baseline survey to guide direction: Each location is unique, and a survey helps to define which resource, recovery, and reuse (RRR) options are most suitable. Questions to ask: Is there enough waste available? Is there a market for fecal sludge or too much competition? Who are the stakeholders? Are there regulatory or community challenges?

Case Study: Balangoda, Sri Lanka

The town of Balangoda (population 35,000) has a successful composting business run by the Balangoda compost plant, a public entity owned and managed by the urban council. Residents pay the council to have their septic tanks emptied. Organic waste separation is encouraged in commercial entities with a fee system for non-compliance. The Government of Sri Lanka provided the funds to construct the plant, which produces around 420 tons of compost a year that can be sold at a 40% higher market price than normal waste compost. Other recyclable material is sold to commercial companies. The two revenue streams recover costs and net some profit, while keeping the streets clear of garbage and providing residents with well-functioning sanitation services.

- Key indicators to determine the costs and benefits of the RRR options: Health and environmental risks must be considered in the same way as monetary and social benefits. Defining the impacts on communities, the economy, and the environment will help policymakers prioritize solutions.

Case Study: Nairobi, Kenya

The Umande Trust runs 57 bio-centers across Nairobi’s informal settlements, in partnership with the Nairobi Water and Sewerage Company. Providing toilet services accounts for about 88% of their revenue, supplemented by sales of biogas generated from the fecal sludge to street food vendors. On average, these bio-centers are used by 1,000 users on a daily basis. As a result, the bio-centers make a profit, the streets are cleaner, and people have access to proper sanitation.

- A business plan: Once the business gets off the ground, it is necessary to develop, grow, and reach more communities and clients. A business plan looks at how to target investors and how to recover and reuse the highest amount of sludge resources at the lowest costs.

Case Study: San Fernando, Philippines

San Fernando (population 115,000) implemented a desludging program through a broad stakeholder consultation process. The city routinely contracted private truck companies to collect and transport sludge to treatment plants, which helped gain efficiencies and thus decrease service charges incurred by households to less than half (from US$ 133 to US$ 66). Even with reduced fees, the private truck operators were happier due to steadier business and more reliable income.

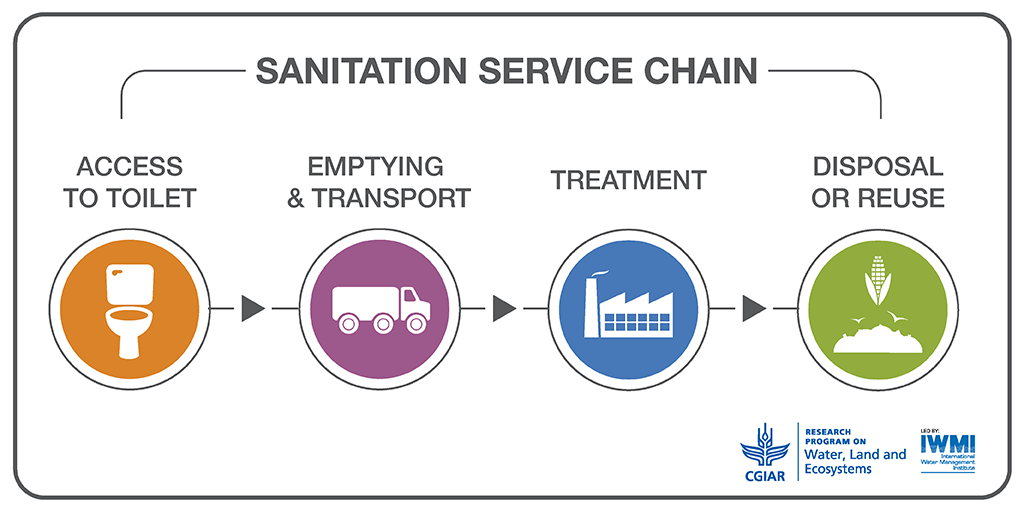

It is clear now, that there is much more needed than access to toilets . Safely managed sanitation services, as presented in Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 6, is a keystone indicator for ensuring that all people have access to clean water and adequate sanitation. This requires more than just providing households with access to toilets. With very little public money and resources available to physically connect all toilets to public sewer systems, identifying and rolling out cost-effective business solutions for on-site sanitation is more crucial than ever—and holds much promise for improving sanitation globally.

Join the Conversation