People salvage usable items from a damaged hotel building and homes caused by floodwaters, in Kalam in Swat Valley, Pakistan

People salvage usable items from a damaged hotel building and homes caused by floodwaters, in Kalam in Swat Valley, Pakistan

South Asian countries have come out of the pandemic with eroded fiscal space and record public debt. Global financial tightening is putting additional pressure on government budgets. At the same time, the region’s vulnerability to climate risks—with more than 800 million people currently living in communities that are projected to become climate hotspots—demands substantial resources to prepare for future disasters and build climate resilience.

These considerations will have strong implications for fiscal management across South Asian countries. First, policymakers must determine how to reduce deficits to rebuild much-needed buffers and regain fiscal space. Second, insurance mechanisms must be put in place to strengthen fiscal capacity. And third, both public and private capital, along with support from the international community, will be necessary for investments in building resilient infrastructure.

South Asia is one of the most vulnerable regions to climate risks. The 2022 Pakistan floods are the most recent testament to how climate-induced shocks can destabilize economies. With thousands dead and more than 33 million affected, Pakistan faces economic losses upwards of US$15 billion.

To prevent a repeat of such catastrophic episodes, it is critical to keep climate change on the planning calendar of every country. The larger the fiscal space available before a disaster, the better the region can build forward post disaster, with reconstruction and social assistance efforts. Such planning also allows governments to provide more resources to build resilient infrastructure, which has an important role in mitigating massive capital and humanitarian costs of disasters.

So how can governments regain fiscal space to meet climate adaptation needs?

- Plan fiscal consolidation. Broadening the tax base by reducing levels of informality and establishing effective reporting and auditing systems through digitalization efforts should help increase revenues. Further, reducing public expenditure inefficiencies like existing fossil fuel subsidies could free up significant public resources.

- Get international support for debt restructuring. For example, renegotiating terms of servicing of existing debt in countries with significant debt vulnerabilities like Sri Lanka will complement fiscal consolidation efforts.

- Scale up the use of risk-transfer mechanisms. For example, climate and disaster risk insurance can mobilize private capital and protect households, firms, banks, and governments from climate-related and other natural hazards. See our Country Climate and Development Reports on Bangladesh, Nepal, and Pakistan. Regional insurance pools such as the Caribbean Catastrophe Risk Insurance Facility (CCRIF), the African Risk Capacity (ARC), and the Southeast Asia Disaster Risk Insurance Facility (SEADRIF) allow countries to pool their risks together and significantly reduce coverage costs.

- Enable sovereign disaster risk finance instruments such as credits or loans with a catastrophe deferred drawdown option (CAT DDO) as in the case of Bhutan, Nepal, Maldives, and Sri Lanka. These countries have developed and implemented these instruments successfully, and they can provide immediate liquidity following a disaster and increase the government’s response without undermining fiscal balances and development objectives.

With more fiscal space, South Asian governments will have more resources to expand resilient investment in the region.

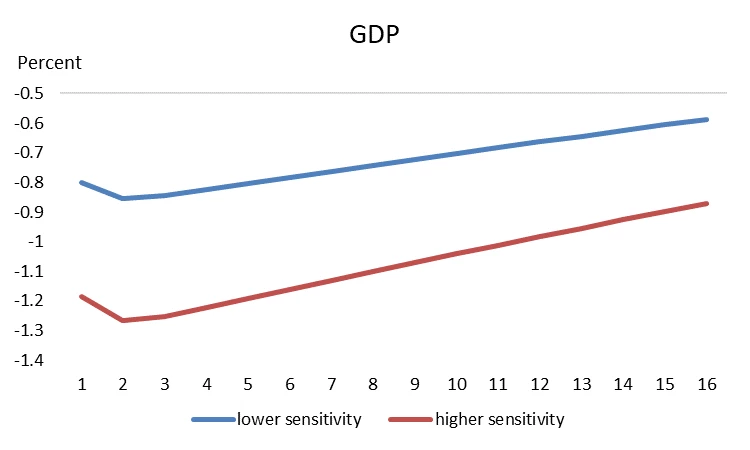

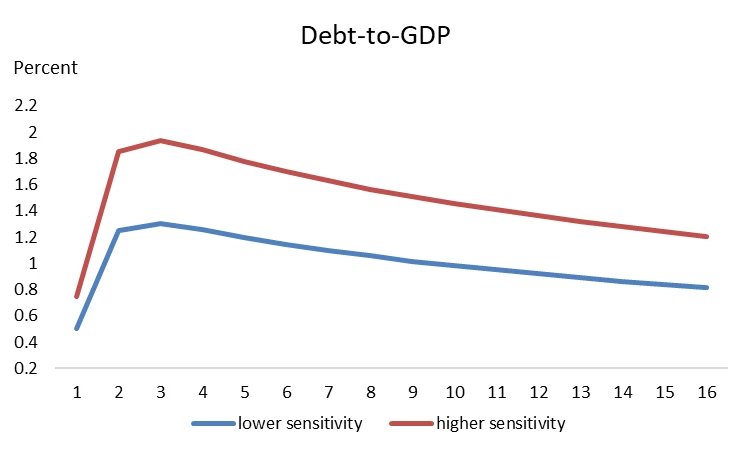

However, public money alone will not be enough to meet the pressing adaptation investment needs. The international community should support country-specific endeavors by mobilizing grants and loans with more generous terms than the ones on the market, through multilateral development banks. It should also help establish new markets for climate-friendly investment and mobilize private capital on a large scale. The reality is, both economic activity and debt are less affected under greater resilience, as shown in the figure below from our latest South Asia Economic Focus Expanding Opportunities Towards Inclusive Growth.

Figure: Both economic activity and debt are less affected under greater resilience

Recent crises have shown that fiscal policy is a powerful tool in fostering resilience across economies. However, disaster-prone countries often have limited fiscal capacity to mitigate the adverse effects of climate-induced shocks. In the World Economic Forum in Davos this year, Pakistan’s climate change minister, Sherry Rehman, warned of “recovery traps”. Given the time and money it takes to rebuild after a disaster, Rehman says, “By the time you do that, the next crisis is on you”.

Credible fiscal management along with more international support are a must to help South Asian countries build greater resilience and avoid getting caught in a never-ending cycle of disaster and poverty.

This blog is part of a series on the Spring 2023 South Asia Economic Focus - Expanding Opportunities: Toward Inclusive Growth

Join the Conversation