Trucks laden with export goods waiting to cross the Indo-Bangladesh border.

Trucks laden with export goods waiting to cross the Indo-Bangladesh border.

“Crossing the India-Bangladesh border is very challenging,” says Bapi Sikdar, an Indian trucker who has ferried cargo between the two countries for 35 years. Sikdar is one of the thousands of truckers who queue up regularly at the Petrapole-Benapole crossing - the busiest and most important land border in South Asia.

Mr. Sikdar had to wait for 15 days just to enter the integrated check post at Petrapole on the Indian side before crossing over. It took him another three days to offload the cargo at Benapole on the Bangladesh side of the border before the job was finally done. In most other parts of the world, including in East Africa, it takes less than six hours to clear similar volumes.

Unfortunately, Mr. Sikdar’s experience is far too common. The long delays at the borders contribute to the high costs of trade between the countries of the BBIN sub-region - Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, and Nepal. These are largely due to the inadequate infrastructure at border crossings, a plethora of paper-based procedures, restrictive policies and regulations, and inefficient logistics for cargo handling.

The complex geography of the area compounds the issue. Bhutan and Nepal are landlocked mountainous countries with difficult connectivity, while the only road within India that connects its north eastern states with the mainland must navigate the narrow Siliguri Corridor, the Chicken’s Neck.

Not surprisingly, these countries find it easier to trade with distant lands than with their neighbors. The World Bank’s Connecting to Thrive report finds it is about 15–20 percent cheaper for an Indian company to trade with Brazil or Germany than with adjoining Bangladesh.

As a result, regional trade has barely scratched the surface of its potential. Although trade between the BBIN countries grew six-fold between 2005 and 2019, the unexploited potential remains massive, estimated at 93 percent for Bangladesh, 50 percent for India and 76 percent for Nepal.

So, what will it take to improve trade and connectivity in the BBIN sub-region?

Cut red tape

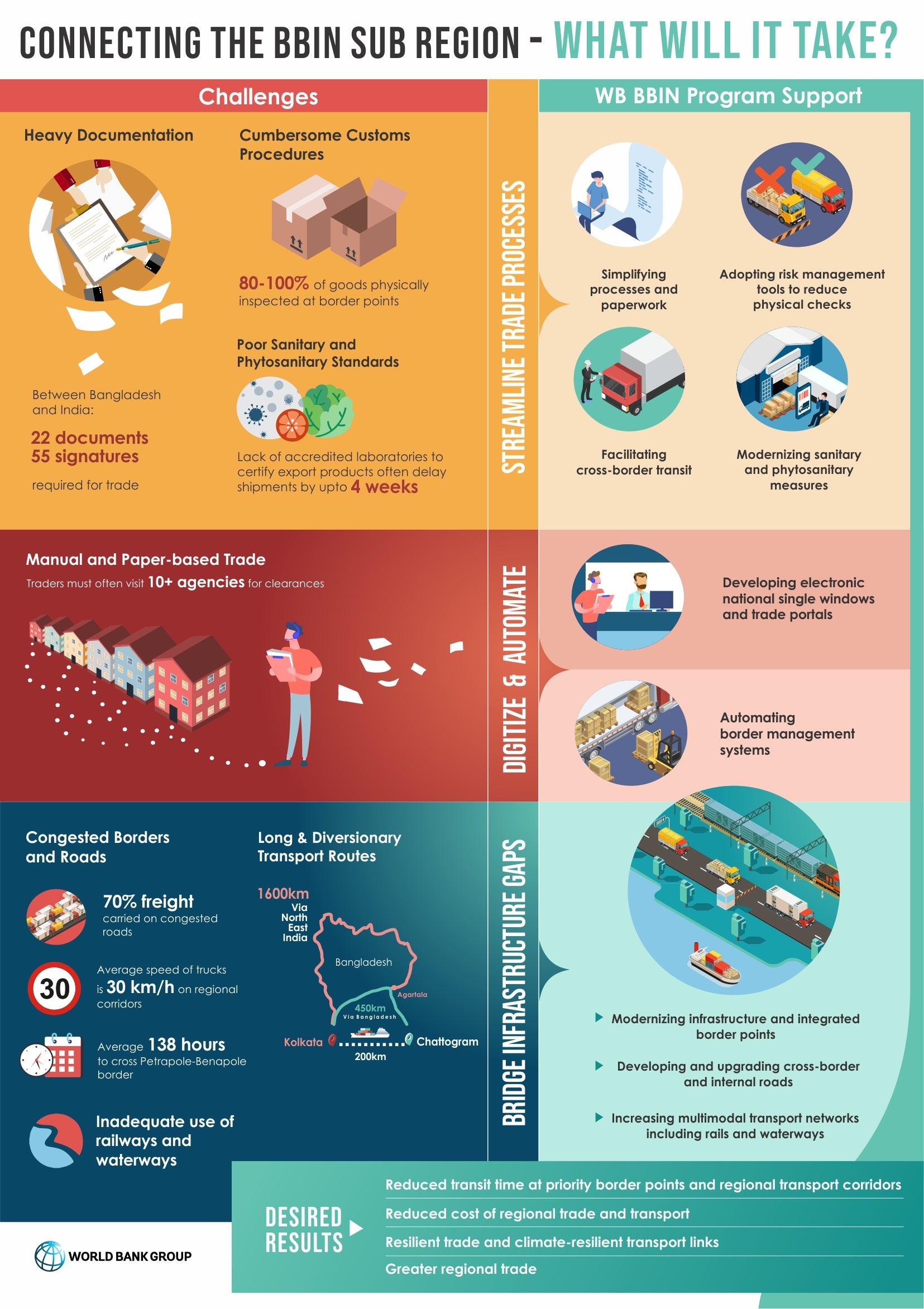

First, simpler regulations will help ease the movement of cargo. At present, around 22 documents and 55 signatures are needed to trade between Bangladesh and India. In Bhutan, importers need to submit their documents to different authorities 86 times on average, while exporters need to do so 74 times.

Second, cutting down the physical inspection of goods can reduce delays. At some borders, customs officials examine 80-100 percent of all the goods that pass through. If countries adopted advanced risk management practices, consignments could be cleared far more quickly.

Third, the early implementation of the BBIN Motor Vehicles Agreement (MVA) can lead to shorter transport routes, quicker travel times, and lower costs, in addition to a smaller carbon footprint. World Bank analysis finds that under the MVA, a truck traveling from Agartala in India’s north east to Kolkata port will take 65 percent less time and be 68 percent cheaper.

In addition, OECD data shows that if countries in the region were to fully implement the WTO Trade Facilitation Agreement (TFA) - which aims to simplify paperwork and harmonize customs procedures - trade costs for lower middle-income economies such as the BBIN nations could come down by over 17 percent.

Digitize, Automate

The digitization and automation of customs and other procedures can also lead to faster and more transparent clearances. Digitization has the added advantage of enabling countries to harmonize their data, facilitating data exchanges and allowing traders and government officials to take evidence-based decisions.

At the moment, however, large gaps remain. While many South Asian countries are moving towards digitization, the United Nations Global Survey on Trade Facilitation and Paperless Trade finds that if this is implemented fully, trade costs can come down by as much as 40 percent.

Towards this end, the World Bank is supporting Bangladesh and Nepal in developing single electronic gateways that will allow importers and exporters to file their documents electronically. Once fully operational, these National Single Windows are expected to dramatically reduce clearance times.

Along with these measures, upgrading procedures for cargo handling, storage, tariff calculation and payment at border points can ease the complexity of cross-border trade.

Bridge Infrastructure Gaps

On the infrastructure front, an integrated multimodal transport network will go far in promoting the smoother movement of goods. Currently, even within nations, multimodal freight operations are limited; this is even less so for cross-border movement. Stronger efforts are needed to move freight onto rail networks and inland waterways to make the most of the multimodal nature of marine containers.

Roads too will need attention. Although roads carry around 70 percent of the freight on these regional corridors, most are crowded two-lane thoroughfares where trucks travel at 30 kilometers per hour or less, and some sections are incapable of carrying larger vehicles or containers. This is especially so for access roads that make the “last mile” transportation of goods slow and inefficient.

A further impediment is the mismatch in handling capacity between the various check posts. While India’s Petrapole border can handle up to 750 trucks a day, Bangladesh’s Benapole point on the other side can only clear 370 of them.

Enormous gains to be made

Together, these measures can bestow enormous benefits on the countries of the sub-region. In Bangladesh, for instance, seamless connectivity with India can raise national income by as much as 17 percent, while India would gain by 8 percent. Bhutan and Nepal can be expected to see similar results, spurring robust, resilient, and sustainable growth across the region.

And Mr. Sikdar, the Indian trucker, can undertake many more journeys, earning him a better income.

Planning for the BBIN transport improvements received funding from Program for Asia Connectivity and Trade, a trust fund supported by the United Kingdom’s Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, and the South Asia Regional Trade Facilitation Program, a trust fund supported by Australia’s Department of Foreign Trade.

Join the Conversation