How can we better understand and reach Armenia’s poor? This is a question that my colleagues and I, along with Armenia’s National Statistical Service (NSS) are asking, as we ponder the experiences of several countries in Latin America and the Caribbean who have moved past simply looking at incomes, and instead used a multidimensional approach to poverty measurement.

First, it is important to understand the context. Armenia is a lower middle-income transition country that managed to reduce poverty by half in two decades – from 54 percent in 1998 to 28 percent by the time of the 2008 global economic crisis. Recovery from the crisis has been uneven, however, and the national poverty rate remained near stagnant at 32 percent in 2013.

How much people spend on food, heating and lighting, and other such items of consumption (which is how we normally measure poverty) certainly remains a good way to capture the living standards achieved by Armenians, but does it really tell us enough about the experience of living in poverty in this ex-Soviet country? Not quite.

For example, a 2002 Word Bank qualitative study of poverty described the new experience of hardships and deprivation experienced by Armenians as Soviet systems collapsed and the new economy emerged. Many of these experiences linger today, such as difficulties with finding adequate heating during winter or finding steady employment.

Moreover, while home-ownership and connectivity to network electricity and water are nearly universal among Armenians, the quality of these services is generally quite low. This type of deprivation certainly can make people feel as though they are living in poverty, even though it may not be captured in our traditional measures.

Add to that an unemployment rate of 16 percent (with job searches lasting 20 months, on average), and it is not surprising that many Armenians feel deprived and impoverished, whether they fall below the poverty line or not.

Against this backdrop, my colleague Moritz Meyer and I began to work with the NSS– the organization tasked with monitoring national poverty – to develop a multidimensional poverty index, which could capture some of these experiences. We did not want to create yet another “poverty number”, but to complement existing consumption poverty estimates and get a more holistic view of the experience of poverty for Armenians.

Ferreira and Lugo point out that the real question facing a poverty economist is not whether to use single or multidimensional poverty measures, but how to best capture the many aspects of welfare and deprivation in order to inform policy makers where to act. We already know a lot about computing poverty using how much people spend on a group of basic goods and services, but we are learning about other things that can help Armenia develop a national multidimensional poverty index.

We started with a “test drive”. We learned a great deal from this multidimensional poverty index (MPI) that was first created by my colleague Josefina Posadas using Armenia’s Integrated Living Conditions Survey (ILCS).

This index builds upon an approach developed by Alkire and Foster, and this “test drive” allowed us to confront several technical choices, many of which involve normative judgments such as choice of unit analysis, selection of dimensions, choice of “cut-off” points to assess if a household is deprived in those dimensions, and choice of weights.

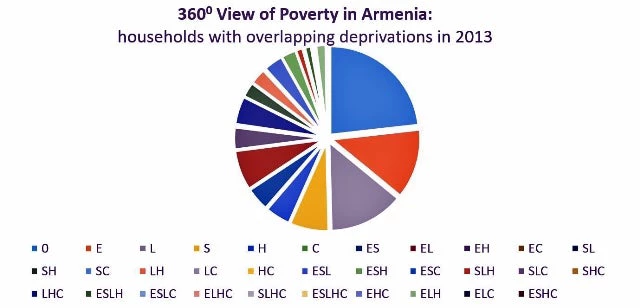

While this index gives the percentage of Armenians who are multi-dimensionally poor, our focus has been to go beyond this and analyze where and for whom these vulnerabilities overlapped. We found that in 2013, only 23 percent of households in Armenia were without any form of deprivation. Moreover, lack of basic, fundamental things like education, health and labor often overlap and show us how households in the country experience poverty not just in one aspect of their lives, but in many.

In 2014, the NSS published the results of this MPI along with an analysis of consumption poverty.

This “test drive” helped us enormously in working with and training our colleagues from the household survey division of the NSS – our main counterpart.

Building upon the “test drive”, our next step is to help the NSS customize the MPI to the country context in Armenia.

This customization will make the index useful not just for poverty monitoring but also for stakeholders and decision makers in the government, as well as development agencies who want to reduce the number of people living in poverty in Armenia.

We kicked off this process on the 3 rd of March this year with a meeting hosted by the World Bank office in Yerevan and attended by the NSS and UNICEF. Two key points emerged from our lively discussion.

First, a national MPI will have to take into account the many different ways people experience poverty throughout their lives- as children, adolescents, adults, and elders.

Second, it will be imperative to involve individual ministries from the outset so that their focus areas are well-represented and they can understand the value of using this index as a guide to better, more impactful policymaking for the people of Armenia.

Related links:

Multidimensional Poverty in Latin America: Concept, Measurement, and Policy

National Statistical Service of the Republic of Armenia

Multidimensional Poverty Analysis: Looking for a Middle Ground

Guidelines for Constructing Consumption Aggregates for Welfare Analysis

Armenia’s Integrated Living Conditions Survey

Multidimensional Poverty Measures Using the Alkire Foster Method

Social Snapshot and Poverty in Armenia 2014

Join the Conversation