In today’s world, international aid is fickle, financial flows unstable, and many donor countries are facing domestic economic crises themselves, driving them to apply resources inward. In this environment, developing countries need inner strength. They need inner stability. And they deserve the right to chart their own futures.

This is within their grasp, and last week the launch of an unassuming-but-powerful tool marked an important step forward in this quiet independence movement. It’s called the TADAT, or Tax Administration Diagnostic Assessment Tool. At first glance, this tool may look inscrutable, technical, and disconnected from development. But listen.

Research shows that if developing countries could simply increase their tax collection by 2 percent to 4 percent of GDP, the amount they raised would eclipse the amount of foreign aid they are receiving. This small relative increase would represent three times the amount of official development assistance distributed in the world. That’s a big deal. And we know that having more taxpayers registered and having more directly contribute to the tax system makes for a more effective state.

And the idea is catching on, globally. At the United Nation’s Financing for Development conference in Addis Ababa in July, the World Bank Group and the International Monetary Fund committed to a joint initiative to help client countries strengthen their tax systems. In addition:

- Thirty countries signed the Addis Tax Declaration, calling for more international support and coordination in this area.

- In September, the UN included in its Sustainable Development Goals this target: “Strengthen domestic resource mobilization, including through international support to developing countries, to improve domestic capacity for tax and other revenue collection.”

- Last week, G20 leaders endorsed the so-called Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) package, designed to curb tax evasion and other illicit tax-related behavior.

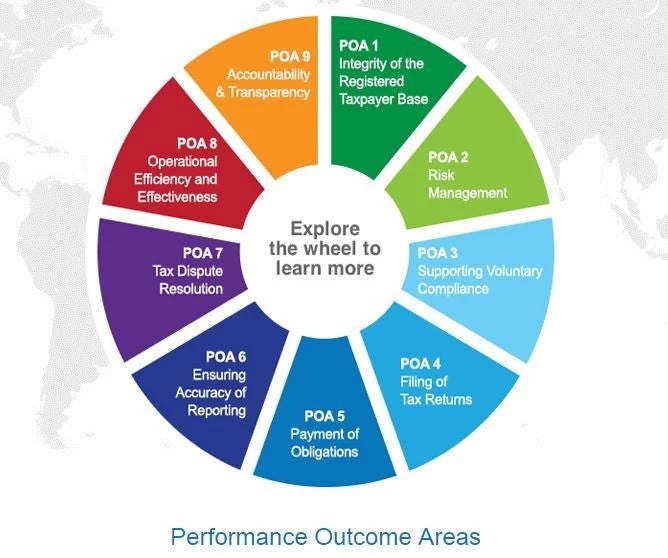

As I said at the TADAT launch event, this tool comes at exactly the right time. The international community is paying attention, and our clients are hungry for technical assistance. This tool will change for the better how we deliver that assistance. It is a move toward transparency, openness, and clarity in how we do analysis. In the past, that assistance has been largely bilateral and uncoordinated – while this is not necessarily bad, it meant that different countries got different types of advice. TADAT brings uniformity to the focus and scope of assessment. With TADAT, even if a regular citizen in Canada or Burundi couldn’t use the tool, she would at least know the categories in which her government is being evaluated.

Yes, Canada. That’s because this tool is equally applicable to developed countries. It looks at all countries, regardless of their level of development, in terms of performance. At the launch event, we heard from two countries that had pilot-tested TADAT: Norway and Zambia. Hans Christian Holte, director general of the Norwegian Tax Administration, said he appreciated that the assessment is evidence-based, and said it was useful in pointing out areas for improvement. He noted that the process was demanding and should be done by people who have a solid understanding of the tool.

Berlin Msiska, commissioner general of the Zambia Revenue Authority, said TADAT showed his administration had a strong governance structure. It validated previous reforms, and identified successful practices. The tool also showed some weaknesses, including in areas that had not received much attention, such as bottlenecks caused by the use of third-party information. He said it “should be embraced like a health check,” and planned to sign up for a re-assessment early next year.

We also heard some debate about how it should be implemented. One audience member suggested opening up TADAT training to people without deep expertise in tax administration, including civil society. Another suggested extending the tool to other agencies that collect revenues, such as those tied to natural resources or taxes charged at the border. And I think that in time, we should be looking at TADAT at a subnational level, where the tax types are different, but the quest for performance is very similar.

One of our jobs now, as development partners, is to guide the use of TADAT in a wide range of contexts – those that include data gaps, corruption, and capacity constraints – and to make sure that we can adapt it to our clients’ needs. Tax policy and tax administration are complex. But we believe they are also essential elements of a well-functioning state. Taxes can strengthen a legitimate relationship between citizens and the state. When they’re well designed, they can help reduce inequality and enable countries to chart their own future. Smart taxation helps growth and development.

TADAT may seem part of a specialized world, but it drives forward a critical, global movement: increasing the financial independence of developing countries. While there’s a long way to go – from analysis to policy reforms to material changes in reducing poverty and improving lives – the movement can’t progress without tools such as this one.

Tweet these:

Having more taxpayers registered and contribute to the tax system makes for a more effective state.

At first glance this tool may look inscrutable, technical and disconnected from development. But listen.

If developing countries increase their tax collection by 2-4 % of GDP, that would eclipse foreign aid.

Join the Conversation