New evidence on the health effects of artificial sweeteners may prompt governments to consider a tax on diet drinks. Copyright: Celso Pupo/Shutterstock

New evidence on the health effects of artificial sweeteners may prompt governments to consider a tax on diet drinks. Copyright: Celso Pupo/Shutterstock

Taxes on sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs)—including most soft drinks, energy drinks, sweetened waters, juices, milk-based drinks, and concentrates used to prepare soft drinks—are internationally recommended as a cost-effective tool for reducing sugar consumption and improving public health. Latest data shows 106 economies, home to 52% of the world’s population, are currently taxing SSBs.

SSB taxes raise prices of, and reduce demand for, taxed beverages. They can also encourage substitution to untaxed products, ideally healthier alternatives. This substitution effect can either support or undermine the public health goals of a tax.

What healthier alternatives should be excluded from SSB taxes?

Unsweetened bottled water is unequivocally a healthy substitute and should be excluded from SSB taxes to encourage consumption. However, whether diet drinks—beverages sweetened with low/zero calorie sugar substitutes, also known as artificial sweeteners—should be excluded has been less clear.

Evidence from the UK and Catalonia, Spain suggests that leaving these drinks out of SSB taxes can strongly incentivize their supply and consumption. In the UK, sales of low- and zero-sugar drinks (not including unsweetened water) rose significantly more than pre-tax trends in the first three years following announcement of the Soft Drink Industry Levy (SDIL), both in terms of absolute volume sales and as a proportion of drinks sold.

Diet drinks are often touted as healthier alternatives but, caution is warranted.

After weeks of media speculation, aspartame has been classified as ‘possibly carcinogenic to humans’ by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), the World Health Organization’s (WHO’s) dedicated cancer research agency. Aspartame is one of the world’s most widely used artificial sweeteners and is almost ubiquitous in diet drinks. The IARC classification is based on limited evidence that the artificial sweetener causes liver cancer. These findings follow a recent WHO guideline advising against the use of artificial sweeteners for weight control.

However, the Food and Agriculture Organization/WHO Joint Expert Committee on Food Additives simultaneously released a summary of its latest risk assessment on aspartame, deeming the evidence for cancer in humans ‘not convincing’ and reaffirming the acceptable daily intake of 40mg/kg body weight.

Governments are likely to be wondering how to convert these new findings into tax policy. We used the World Bank Global SSB Tax Database – an open source of data on SSB tax designs worldwide - to see what countries are currently doing.

Many governments already tax diet drinks, particularly in lower income economies.

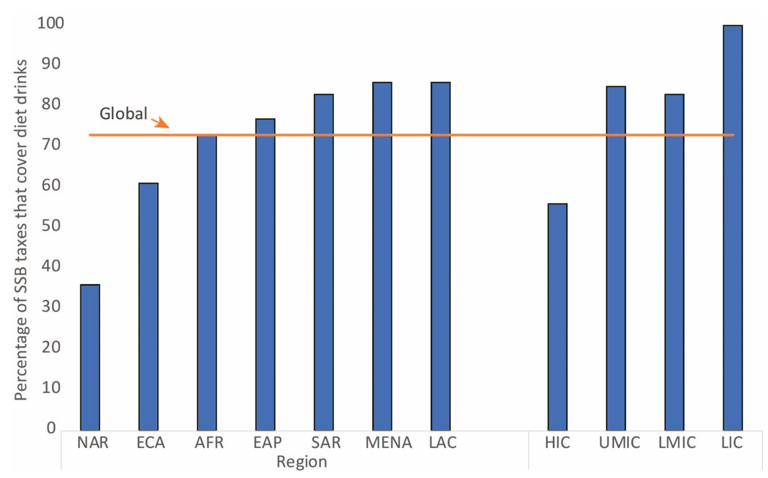

Contrary to perception, most governments already include diet drinks in their SSB taxes. Three out of four SSB taxes worldwide, and all SSB taxes in low-income economies, apply to diet drinks. These drinks are much more likely to be taxed in Latin America and the Caribbean, and in the Middle East and North Africa, than in North America or Europe and Central Asia (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Proportion of SSB taxes that cover diet drinks, by region and income group, Feb 2023

Some governments have singled out diet drinks (drinks containing artificial sweeteners) as targets for taxation, including in Croatia, Poland, Spain, and the Philippines. For example, the Philippines applies an excise tax of PHP 6 per liter for drinks containing added sugar or artificial sweeteners, and PHP 12 per liter for drinks containing high-fructose corn syrup.

More commonly, however, diet drinks are included in SSB taxes by default. This is because the Harmonized System of Tariff Codes used to identify taxed products does not distinguish between added sugar and artificial sweeteners.

If governments want to tax diet drinks, what are the considerations?

When it comes to diet drinks, the latest guidance on artificial sweeteners will need to be carefully considered alongside other factors, including tax objectives, local beverage market structure, and potential substitution effects.

While the evidence is weak at this stage, the potential for consumption of artificial sweeteners leading to adverse health effects cannot be ruled out. This suggests the need for caution, with priority given to encouraging substitution towards drinks that are less sweet. An immediate priority is to ensure that unsweetened bottled water is excluded from SSB taxes and encouraged as the healthiest substitute. Roughly one third of all SSB taxes worldwide, and more than half of taxes in low-income economies, currently apply to unsweetened bottled water.

At the same time, excluding diet drinks tends to lower industry opposition to a tax, given the market opportunities provided (e.g. for reformulation and new product development). Some governments may see this as an opportunity to get a new tax adopted, with the potential to refine its design down the track, including products included in the tax. In other cases, industry opposition may be overcome by a strong evidence-based rationale and public support for taxing diet drinks.

If governments opt to tax diet drinks, using standard Harmonized System tariff headings for non-alcoholic beverages will cover these drinks unless an explicit exemption is made.

However, taxes based on the amount of sugar (e.g. 5 cents per gram of sugar) will need additional provisions for diet drinks. One relatively straight-forward option is to use a mixed tax structure, with drinks containing artificial sweeteners taxed based on volume (e.g. 5 cents per liter). Poland applies a base tax of PLN 0.50 per liter on all drinks containing added sugar or artificial sweeteners, with an additional tax of PLN 0.05 per gram of sugar over 5 grams sugar per 100ml. An additional tax of PLN 0.09 per liter is also applied to drinks containing caffeine or taurine.

Colombia’s upcoming tax on SSBs and ultra-processed foods, set for implementation in November 2023, is expected to apply to drinks containing both sugar and artificial sweeteners using a nutrient-profile based approach. This could provide a model for future taxes on unhealthy foods and beverages in other countries.

To receive weekly articles, sign-up here

Join the Conversation