Agricultor en La Esperanza, Intibucá, Honduras

Agricultor en La Esperanza, Intibucá, Honduras

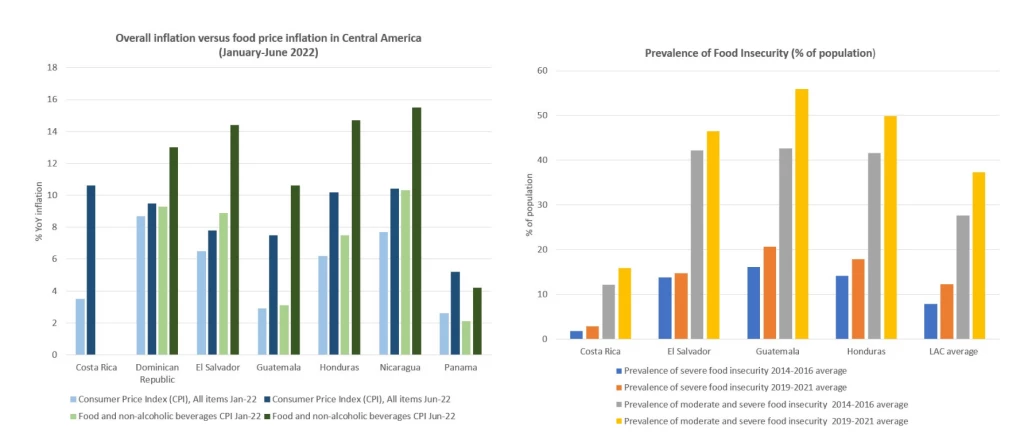

Edwin, a farmer in La Esperanza, the small capital of the Intibucá department of Honduras, has seen the cost of his bag of fertilizer increase from US$20 to US$40 from one productive season to another since September 2021. The cost of fertilizers has increased so dramatically across Central American countries that resource-constrained farmers like Edwin are having to reduce the fertilizer amount they use, plant less, and increase prices of the crops they sell. These responses threaten further increases in food insecurity in a region where food inflation is escalating (Figure 1). So why are fertilizer prices so high, and what can countries do about this?

Figure 1. Inflation and food insecurity in Central America

The global fertilizer market

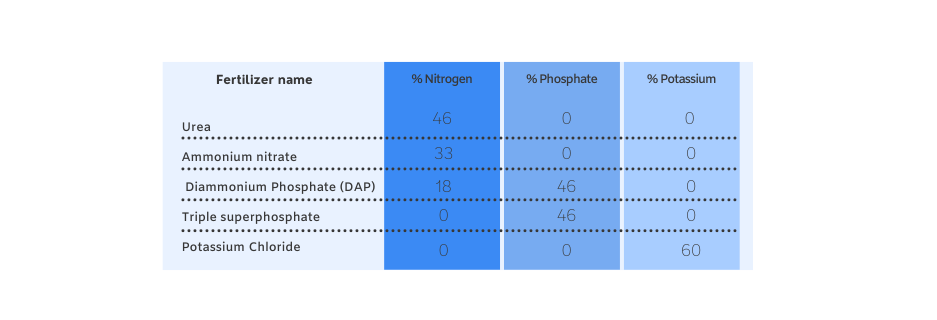

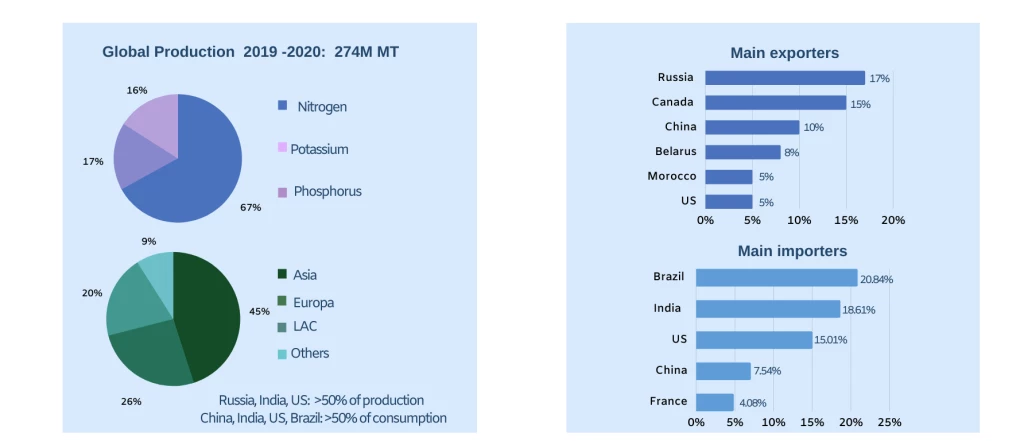

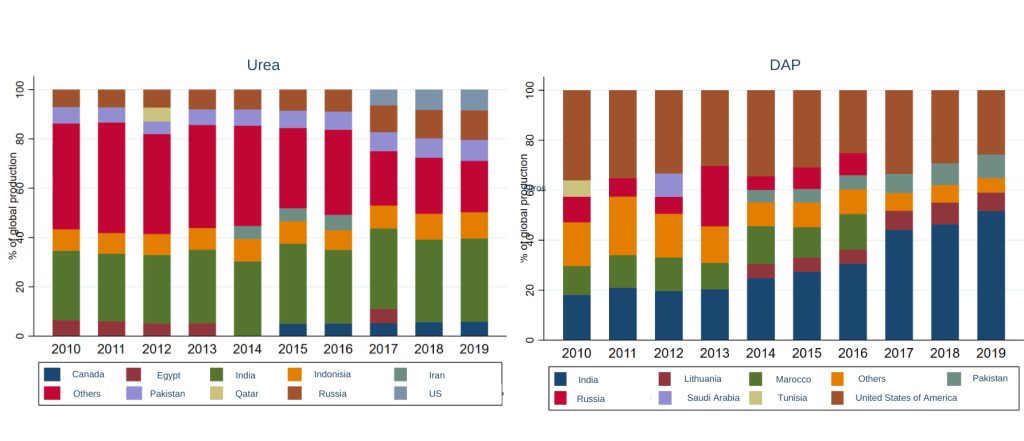

Granular (solid) fertilizers (as opposed to soluble ones) are the most used chemical fertilizers by small and medium farmers in Latin America (80-90 percent use them), because they are less expensive and do not depend on the availability of irrigation. Global production of fertilizers revolves around three primary nutrients (Nitrogen, Potassium, Phosphorus), which are combined into different blends (Table 1). Nitrogen-based granular fertilizers such as urea and diammonium phosphate (DAP) account for roughly two-thirds of global fertilizer production (Figure 2). The key raw material inputs for Nitrogen-based fertilizer production are air and natural gas (respectively a source of Nitrogen and energy). As such, countries with access to natural gas, like Russia, Canada, Belarus, and China, are the main producers and exporters of Nitrogen-based fertilizer. The global market for specific fertilizers has also become more concentrated over the years: in 2019, India and Russia accounted for 46 percent of urea production, while 75 percent of DAP was produced in India and the United States (Figure 3).

Table 1. Popular granular fertilizer formulas

Figure 2. Major global producers, consumers, exporters, and importers of granular fertilizers

Figure 3. Major global sources of Nitrogen-based fertilizers

Note: The residual category “Others” sums up countries with share < 5%

The co-dependence of energy, fertilizer, and food prices

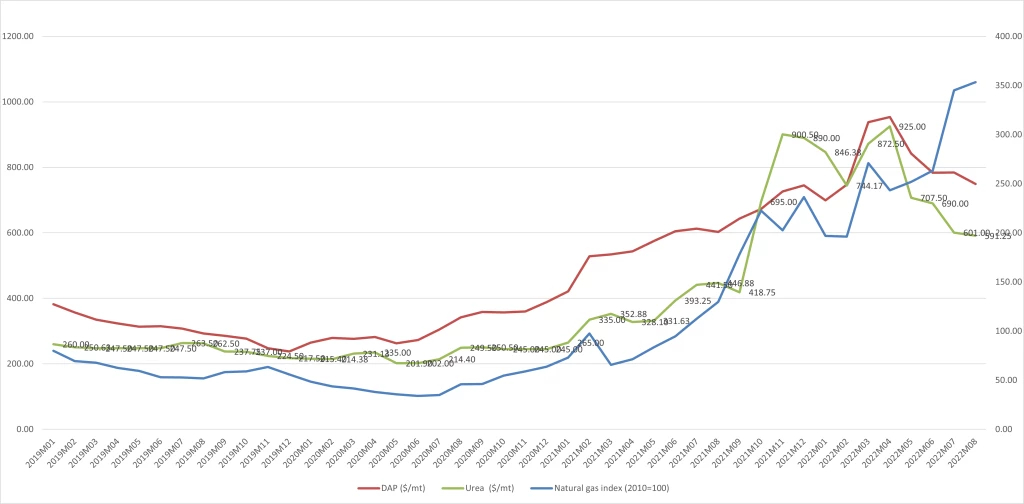

Due to the important natural gas component in the production of Nitrogen-based fertilizers (gas represents around 80 percent of production costs for urea), global fertilizer prices are linked to global natural gas prices. Global fertilizer prices have been on the increase since late 2020 , as a consequence of COVID-19-induced disruptions to logistics chains and high energy prices, followed by tropical storm Ida destroying natural gas factories in the Gulf of Mexico in 2021. At the end of September 2021, as early signs of pandemic recovery led to higher fuel and natural gas prices, urea and DAP prices jumped respectively to 300 percent and 200 percent of their value in September 2020. In 2022, the Russia-Ukraine crisis has triggered a more aggressive hike in energy and fertilizer prices, because of the inability of Belarus and Russia to export to certain markets (Figure 4).

Figure 4. DAP and Urea market prices compared to natural gas prices (Jun 2019 - Aug 2022)

Local fertilizer markets

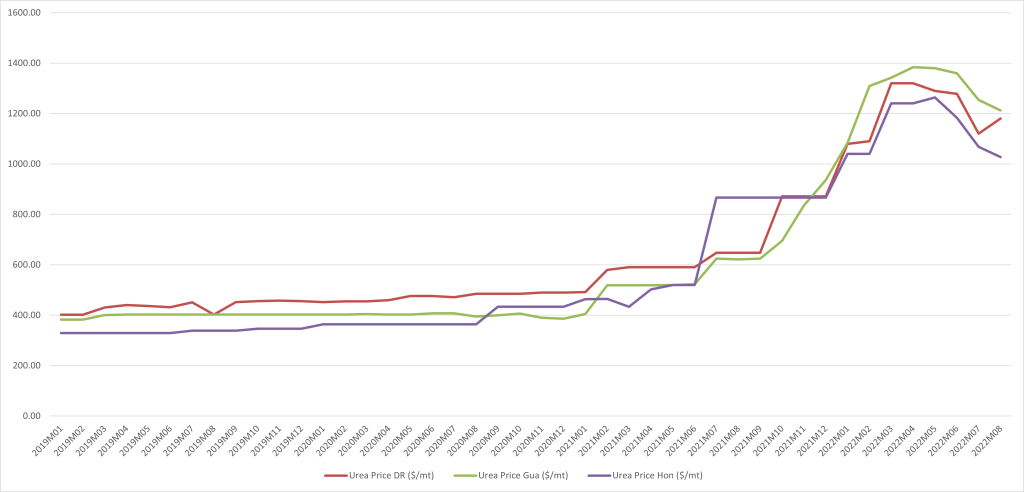

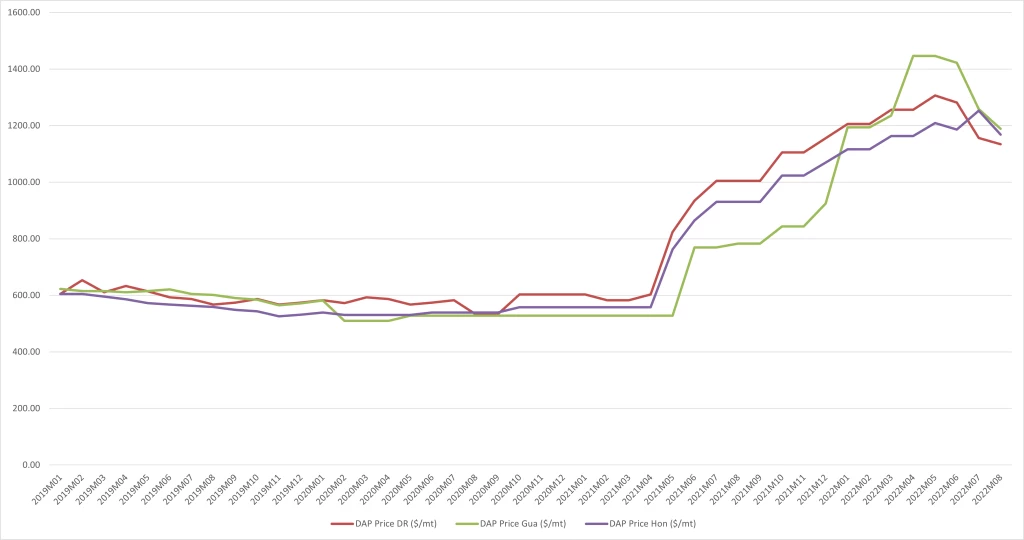

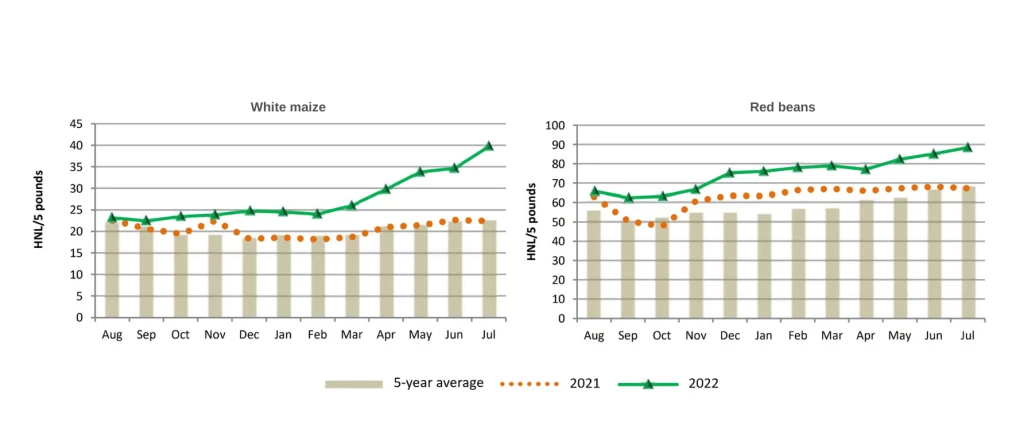

Before the Russia-Ukraine conflict, Central America imported fertilizers from Russia, Belarus and Ukraine, and this has had a direct impact on local fertilizer prices (Figures 5 & 6). Local prices are also impacted by the cost of fuel and logistics in the domestic fertilizer supply chain, from port to farm, which has doubled in some Central American countries . Based on our interviews with farmers in these countries, the cost of granular fertilizers as a share of total production cost per hectare has increased between 45 and 66 percent for basic staples such as maize, beans, rice, and potatoes from 2021 to 2022. These increases are much higher for farms far away from the central warehouses of fertilizer distribution companies. As a result of higher production costs, local food prices are soaring (Figure 6). And things can get worse in the future if fertilizer use is reduced and food production contracts (today, around 50 percent of basic grains in the region are produced using granular fertilizers). In Honduras, one in five farmers already indicates having reduced the planting area for maize, beans, sorghum, and rice.

Figure 5. Urea farmer prices in the Dominican Republic, Guatemala, and Honduras

Figure 6. DAP farmer prices in the Dominican Republic, Guatemala, and Honduras

Figure 7. Local food prices in Tegucigalpa over the years

What can countries do?

Immediate policy responses to address the increase in fertilizer prices are emerging across the region . The Dominican Republic is compensating granular fertilizer companies to maintain constant retail prices, while Honduras and Guatemala have expanded their national programs for vulnerable farmers by distributing free bags of certified seed and fertilizer. There is also widespread revived interest in the production and use of organic fertilizers. In line with lessons learned from previous food price crises, the following are three recommendations for Central American countries:

- Targeting: Not all farmers use fertilizers, and some farmers have specific fertilizer needs depending on agroecological conditions and commodities produced. Properly targeting the farmers in need of support is critical.

- Avoid market distortions: In most countries, there is an active domestic fertilizer market. It is important that public support builds on this private market and does not substitute it. Rather than engaging in public purchases of fertilizers or the physical distribution of fertilizer bags, vouchers would be preferable to ensure that farmers can acquire the fertilizer type they need.

- Enhance medium-to-long-term productivity: While taking advantage of short-term support (subsidies) to accessing fertilizers, a medium-term, strategic agenda should address key issues related to soil fertility and plant nutrition management, improving farmers’ production efficiency jointly with soil and environmental health.

For Edwin, in the long run, having an option to purchase biofertilizers, getting technical assistance to increase the efficiency of fertilizer application, and improving soil and crop fertility, would go a long way in making his farm’s production more sustainable and resilient to future shocks.

Join the Conversation