A woman works in front of a computer in the call center of the main offices of Edesur (Electricity distribution company), in the Customer Service area of the country's electrical network, on June 25, 2021 in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic

A woman works in front of a computer in the call center of the main offices of Edesur (Electricity distribution company), in the Customer Service area of the country's electrical network, on June 25, 2021 in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic

“Download our app or purchase through our WhatsApp number, small shipping fee.” “Contactless shopping by just scanning the QR code.”

For Latin Americans, messages like these are now increasingly commonplace. Since the region’s governments started implementing COVID-19 containment measures, back in April 2020, they have been popping up everywhere – in shops, on billboards, at the supermarket. They provide just one illustration of how digital connectivity has helped to mitigate the everyday impacts of the pandemic.

By linking together friends, family, students and teachers, firms, and markets, digital technologies have been crucial in enabling a variety of social and economic activities to continue. As well as providing relief for millions of people, such connectivity has proved critical in addressing wider societal challenges created by COVID-19 restrictions.

The value of such technologies is especially clear when considering how people have adjusted to the ‘new normal’. As our new report "The Welfare Costs of Being Off the Grid" reveals, digitally connected households have adapted far more quickly and effectively than their less connected counterparts.

Likewise, the less-connected have experienced greater welfare losses, including learning losses, than their better connected neighbors. These results are valid even when we account for similar background characteristics such as education, area of residence, and the dependency rate, defined as the ratio of dependents (too young or old to work) to those of working age.

Connectivity, the key to the future

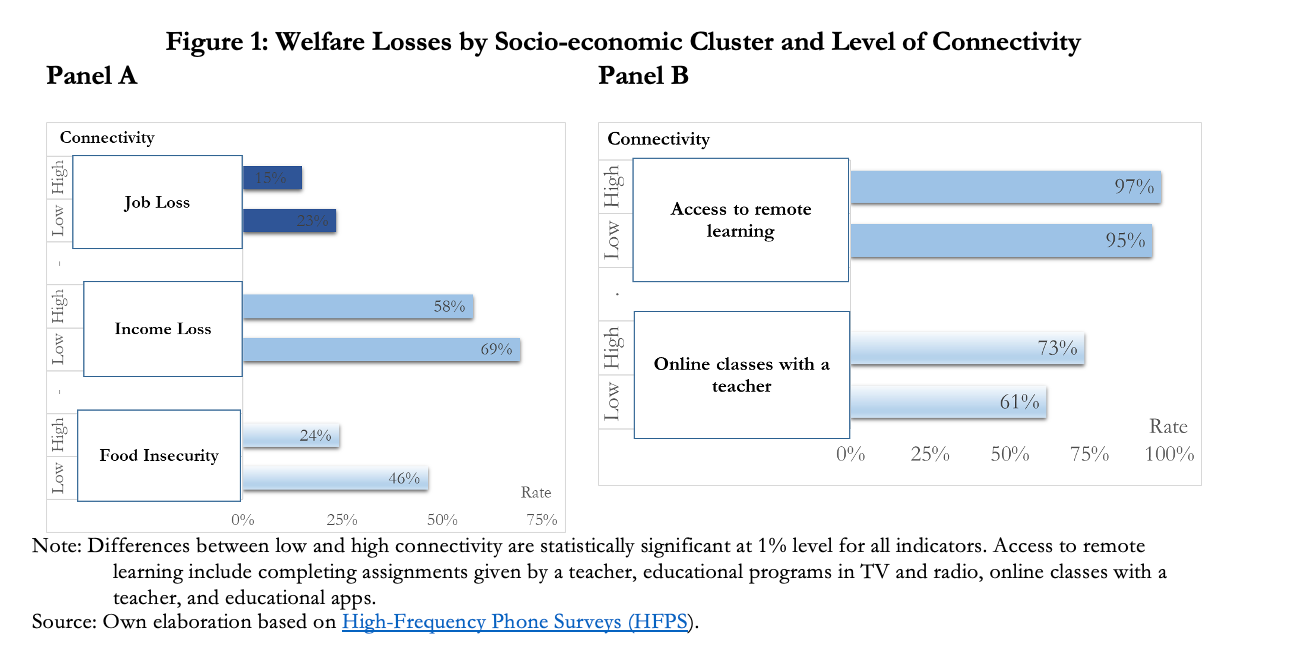

Take households that primarily reside in rural areas, whose members have less than secondary education and relatively high dependency rates. Those with high digital connectivity registered a lower level of employment loss (15%) than their low-connectivity counterparts (23%). Similarly, 69 % of low-connectivity households suffered a reduction in their total family income, 11 percentage points more than their highly-connected peers. Food insecurity levels were almost twice as high for those with lower connectivity, 46% versus 24% (Figure 1, Panel A).

Equally important, or even more important considering the long-term consequences, households with high digital connectivity were able to access remote learning activities of better quality. While access to any remote learning activity was high for low and high connectivity households, the latter group was able to access higher quality learning activities such as online sessions with a teacher and virtual assignments (73% versus 61%, Figure 1, Panel B). Thus, connectivity helped to curb the effects of the pandemic on the human capital accumulation of children, particularly in vulnerable households.

Almost two thirds of the residents in Latin America and the Caribbean have access to the internet, but there are significant disparities between and within countries. Less than 50% of the population have fixed broadband connectivity, and only 10% have fiber-to-home.

To ensure that all segments of the population have access to digital technologies and can reap their benefits, significant investments in infrastructure are required. This is particularly true for rural areas, where only 40% of the population is connected.

Affordability is also a major challenge to achieve widespread connectivity. For the average household in the region, the cheapest smartphone represents around 12% of monthly income, but for Guatemala and Nicaragua costs can be as high as 34%, and for Haiti a staggering 84%. Reducing taxes and customs duties on low-cost internet-capable devices can help bring down prices that exclude the poor.

Technology permeates peoples' lives through multiple channels, with work, consumption, education, and health some of the most obvious examples. People and households will only benefit from digital dividends if they know how to use technology.

That is why the digital agenda should also promote digital skills throughout the life-cycle of individuals. These skills are particularly important for those trying to rejoin the labor market in the context of recovering economies but also for those accessing public services during the pandemic.

Latin American governments are increasingly taking note, and recognize the importance of formulating a digital policy agenda that encompasses investing in digital infrastructure, improving digital government services (e-government), developing digital skills and enhancing connectivity among marginalized segments of the population. Connectivity is the key to the future and there’s no time to postpone this agenda.

Join the Conversation