Many countries have made significant progress in improving human capital over the past several years, as the recently published 2020 Human Capital Index (HCI) update shows. But many of the hard-won gains, especially in narrowing gaps between girls and boys, are now threatened by the pandemic.

The Universal Children’s Day today is a reminder that girls and boys are our future and investing in their human capital must a be priority for governments and societies to ensure a sustainable recovery from the current crisis.

A quick glance of HCI shows measured human capital is higher for girls than boys in 140 of the 153 countries that have sex-disaggregated data—tempting one to conclude “mission accomplished” in closing gaps between girls and boys.

But is the job really done?

To reflect on that question, we need to unpack the HCI’s five important components:

- Survival and health – infant survival, adult survival, and stunting rates

- Education – expected years of school and harmonized test scores

and what they do and do not capture.

Girls have biological and behavioral advantages over boys in survival and health

Globally, infant mortality is 14% lower for girls than for boys, and girls on average are expected to live 4.5 years longer than men. Since 1960, with the exception of South Asia, girls constantly had higher life expectancy at birth than boys.

Many factors contribute to this regularity. For example, masculine norms may prescribe boys and men to specific behaviors harmful to their health. Men in strongly patriarchal societies may ignore illness or avoid seeking medical help, to avoid being perceived as weak by their peers. Men are also 5.4 times more likely to smoke and consume 4.6 times more alcohol than women.

2.Girls have made significant strides in educational attainment in recent years

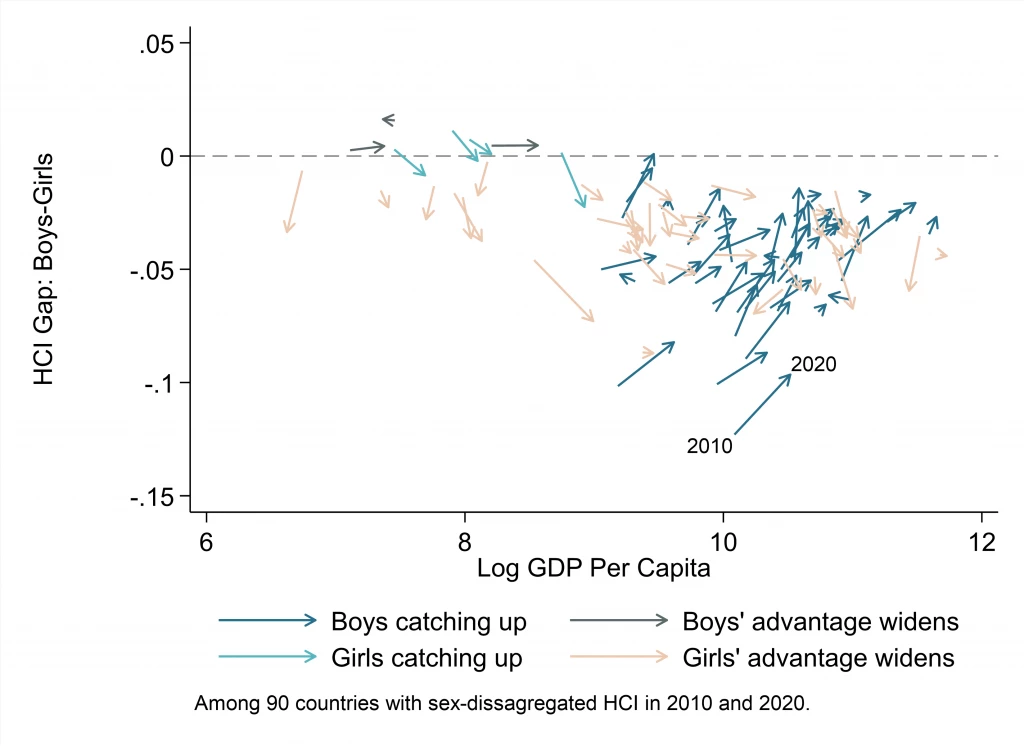

The key progress in gender parity has been on education. But girls catching up to or even overtaking boys in education is a recent phenomenon. While the 2020 HCI update includes a data point from 2010, 2010 is still too soon to illustrate the long-term trend of convergence. This blog shows how much the gender gap in educational attainment has shrunk among the young population, especially in recent decades. However, large gender gaps remain in education among the current adult population (as measured by their literacy rates).

3.There are important facets of human capital, not measured by the HCI, and data show that girls are at a disadvantage compared with boys

In terms of health, there is the issue of stubbornly high maternal mortality. It is girls who exclusively face challenges related to maternal mortality and sexual and reproductive health—particularly in poorer countries. Maternal mortality is 41 times higher in low-income countries than in high-income countries. In Sierra Leone, one in 20 women will die in childbirth.

The education components of the HCI importantly distinguish years spent in school vs. learning. However, the HCI does not reveal the fields of study that boys and girls stream into, and the continuing underrepresentation of girls in STEM. For example, as this blog shows, globally, only one in four students pursuing careers in information, communication, and technology fields are female.

4.Getting to equal means equal considerations for both boys and girls

For most part of the past 30 years, closing gender gap has been synonymous with improving girls’ outcomes. However, emerging patterns show that boys are being left behind. In fact, in 54 of 90 countries with sex-disaggregated data in both 2010 and 2020, gender gap shrunk where boys are catching up to girls’ advantage.

Policies need to address different and specific constraints faced by boys and girls to ensure that boys and girls can grow equally in their human capital. Sometimes, the most effective policies do not necessarily target girls (or boys) specifically, but rather, they address a constraint to improved health and education which is more binding for girls (or boys).

Making secondary education free for all, for example, can be as effective at improving girls’ enrollment as giving girls subsidies to attend schools. In settings where girls would miss school during their menstrual cycle, better menstrual hygiene management can help address this challenge. The gender norms that deem that boys and men need to work instead of spending time in school may be addressed by a curriculum-wide change to help overcome gender bias or stereotype and promote strategies to cater to a wider variety of learning styles and needs. In addition, introducing non-stereotypical role models (for example, male caregivers) may expand boys’ vocational options.

5.Accumulated human capital does not necessarily get utilized

The HCI implicitly assumes that when children grow up, they will be able to utilize their human capital. However, considerable gaps in labor market opportunities between men and women are well documented. Globally, only 64 women for every 100 men participate in the labor force. This blog discusses some recent lessons learned explaining low female labor force participation.

Underemployment of women represents a wasted potential, especially with increasing gains in the human capital of girls. The newly developed Utilization-adjusted Human Capital Index (UHCI) takes this into account. The UHCI provides a more nuanced picture of both investments in human capital and how those investments are realized in terms of labor output for workers.

6.The COVID-19 pandemic poses a grave challenge that could wipe gains in human capital for both boys and girl

Widespread unemployment and income loss accompanying the COVID-19 pandemic are severely testing households’ ability to keep students in school. Households may resort to marrying girls early to cope with the negative income shock, while boys are sent to enter the workforce. During school shutdowns, adolescent girls may spend more time with men, increasing the likelihood of getting pregnant as well as their chances of permanently leaving school.

The data have shown that gender gaps can close when societies make concerted efforts. Yet, gender parity in measured human capital is a recent phenomenon and disparities still persist, not only for adult women, but also for young girls in a variety of human capital dimensions. At this time, we can’t yet say “mission accomplished.” But we can certainly work together—governments, families, the private sector—to make gender parity “mission possible.”

Join the Conversation