NAS, including Gross Domestic Product (GDP), are typically measured by reference to the economic structure in a “base” year. Statisticians sample businesses in different industries to collect data that measures how fast they are growing. The weight they give to each sector depends on its importance to the economy in the base year. As time passes and the structure of the economy changes, these figures become less and less accurate.

Re-basing is a process of using more recently collected data to replace an old base year with a new one to reflect the structural changes in the economy. Re-basing also provides an opportunity to add new or more comprehensive data, incorporate new or better statistical methods, and apply advancements in classification and compilation standards. The current gold standard is the 2008 System of National Accounts (SNA).

One can think of re-basing as taking a more recent snapshot of the economy using the latest camera technology, where one can truly see the photo’s quality and sharper details. The more frequent updates and better quality of Kenya’s NAS explain, in part, why the re-basing exercise did not result in the massive changes in GDP as witnessed in Nigeria and Ghana (by approximately 60 percent and 63 percent respectively).[1]

Some key Kenya National Accounts Statistics re-basing facts:

- The size of the economy is 25% larger than previously thought, and Kenya is now the fifth largest economy in Sub-Saharan Africa behind Nigeria, South Africa, Angola and the Sudan.

- The structure of the economy remains largely unchanged in broad sectoral terms.

- Kenya crossed the lower-middle income country threshold in 2012.

False, because even though the re-basing exercise is indeed retroactive, it has major forward looking implications because the structure on which more current estimates (or forecasts) are based is more up-to-date. Take Kenya’s public debt-to-GDP is one such ratio, which has decreased as a result of re-basing from 52% to about 43%. This provides more borrowing headroom for Kenya, which has clearly forward looking implications (especially if new borrowing can be used to retire more expensive debt incurred in the past and if this borrowing is used for development spending).

On the flip side, Kenya’s tax revenue-to-GDP ratio has worsened from about 23% to 19 %. The forward looking implication of this is clear: the authorities need to do much more in terms of broadening the tax base and closing tax loopholes than they have done so in the past.

Myth 2: Re-basing disqualifies Kenya from WBG concessional financing.

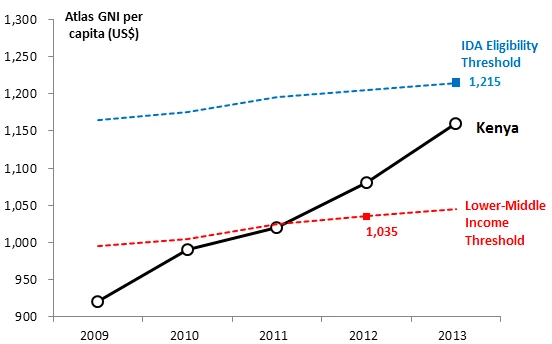

False, because while the re-basing results show that Kenya crossed the middle-income threshold in 2012, Kenya remains eligible for concessional financing from the Bank’s International Development Association (IDA) window. The World Bank Group country income classifications are often confused with our operational categories. Both are based on Atlas US$ GNI per capita measures, but the cut-off thresholds differ. Currently a country’s GNI per capita must exceed USD 1,045 to be classified as lower-middle income. But the IDA eligibility cut-off currently stands at a GNI per capita of USD 1,215. Kenya’s 2013 GNI per capita of USD 1160 is now above the lower-middle income threshold (of USD 1035), but still below the IDA eligibility cut-off (of USD 1215).

Moreover, a country needs to exceed the IDA threshold for at least three consecutive years before becoming ineligible for financing from IDA. The process is governed by a number of additional factors (including creditworthiness) as per the Operational Policy statement OP 3.10.

Kenya’s GNI per capita: in between the IDA eligibility and lower-middle income thresholds

On the consequences

Some key implications of GDP re-basing can be viewed through a macroeconomic indicators lens. As mentioned above, the debt-to-GDP and fiscal deficit-to-GDP ratios have declined. However this does not necessarily mean that Kenya should borrow more or even have larger deficits. Even though the capacity of the economy to absorb more debt is larger than we had previously thought, with a larger GDP, the ability to service those debts is a function of tax revenues and export receipts which have remained unchanged. Depending on how they are financed, fiscal deficits can either add pressure on domestic interest rates if financed through local borrowing or add pressure on the exchange rate if borrowing is financed externally.

The re-basing exercise has also exposed structural inadequacies—including the unbalanced growth pattern—which policymakers need to address. Exports as an engine of growth remains stalled and needs to be fired up. Exports of goods and non-factor services as ratio of GDP stand at 16.7% compared to imports at 29%. Despite its potential to balance growth and create jobs, exports are underperforming.

On the economics of National Account Statistics re-basing and statistical capacity building

NAS re-basing is a data intensive process and requires a number of firm-based and household-based surveys that are both time consuming and costly. Most of the surveys which enabled the Kenyan re-basing to be undertaken were financed by the World Bank Group and other development partners. Despite the cost, investment in statistics has huge benefits to the country not only in terms of monitoring and evaluation of government policy. The financial returns can also be significant. For example, recent research suggests that attaining SDDS ( Special Data Dissemination Standard) status could translate into a 0.5% savings on yields of sovereign bonds. If we take the Kenya’s USD 2 billion euro bond debut as an example, the country would have saved USD 10 million annually for the duration of the bond.

The KNBS has developed a 5 year strategy to improve statistics in Kenya including key milestones towards achieving the SDDS status. The government has requested the Bank Group’s technical and financial support to implement this strategy. The pipeline Kenya Statistics Programs for Results is a USD 50 million credit being designed to answer that call.

Join the Conversation