During a recent trip to Dushanbe and Bishkek, we were really impressed by the beauty of the two cities. - they both benefit from a legacy of urban planning that features well-manicured parks and greenery, wide pedestrian paths and ample public spaces. We enjoyed walking along Rudaki Avenue in Dushanbe, as well as Erkindik Avenue in Bishkek, both of which are lined with lush, tall trees that provide shade from the sunlight and heat.

Another legacy is the trolleybus system, which dates back to the 1950s. At this time, trolleybuses were the dominant travel mode in both cities. Today, however, the number of trolleybus routes and the overall fleet size have reduced significantly, accounting for just 2 percent of all motorized trips. The decline in the use of trolleybuses was caused by a lack of maintenance, decreasing profitability, the emergence of competing travel modes, and travelers’ changing expectations.

At the same time, the trolleybus is considered one of the most eco-friendly and economical transport modes in the Central Asia region. Trolleybuses are powered by relatively cheap electricity that is mainly generated by hydropower. That is why both cities are now planning to renew their trolleybus fleets and upgrade the necessary infrastructure, with donor support.

Regular bus fleets, which are operated by communal bus companies, are also in decline – largely due to regulated fixed fares (which are insufficient to meet operating expenses), a high number of fare exemptions for multiple categories of people, and the inability to provide state subsidies on a stable basis. In addition, regular maintenance is often deferred due to a lack of spare parts. In Dushanbe, less than 60 percent of the available bus and trolleybus fleet are operating on the road today.

It’s understandable, therefore, that many people here are nostalgic about a time when public transport was cheaper and of better quality.

When the formal public transport sector failed to address the travel needs of local people, a new option emerged: marshrutkas – privately-run minivans with fixed routes. Today, there are over 1,300 marshrutkas in Dushanbe and over 2,400 marshrutkas in Bishkek. During the evening rush-hour period, large public buses and trolleybuses usually arrive every 6-8 minutes – but marshrutkas arrive every few seconds. The popularity of these informally-operated buses has been boosted by their ability to navigate narrow and poor-quality roads and serve outlying low-density areas, and their flexibility in meeting diverse demand. In Bishkek, the new settlements on the urban fringes (known as novostroyki) are mostly served only by marshrutkas.

Nevertheless, these minivans are not without problems or disadvantages. Although they are meant to carry no more than 12 people, they often take more than 30 passengers. Drivers compete for passengers, and oftentimes they don’t come to a complete halt on the street, forcing passengers to leap from the moving vehicle. Moreover, the majority of the marshrutkas are over 15 years old, running on EURO-II diesel and emitting high levels of pollutants. They are also more expensive (by around 25-40%) than regular buses.

Both cities have plans to expand their bus and trolleybus networks and to replace the marshrutkas with formal transit in their city centers. They also plan to limit the operations of marshrutkas on the outskirts of the cities. However, simply replacing small buses with large ones without addressing people’s travel needs and patterns is not the solution. In the past, attempts to restrict minibuses on certain corridors have led to an exponential rise in taxis, which makes traveling even more expensive and adds to congestion on the streets.

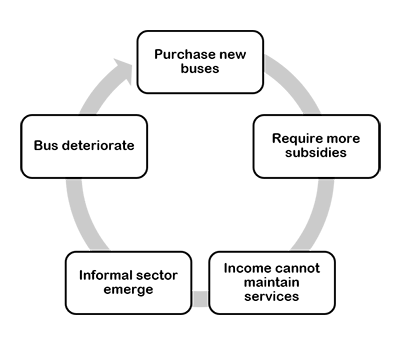

For the city authorities to commit to procurement of new buses, either in response to popular demand or as a means to establish state control is nothing new. But in absence of associated reforms, the decision has often resulted in a vicious cycle with an eventual decline in service standards (see Figure above).

What these cities need is a comprehensive approach to supporting a multi-modal network that will serve the diverse needs of commuters.

The above picture is my favorite from our trip – it’s of a bus packed with Tajik kids with big smiles waiving to us foreigners in the street.

We believe that public transport is meant to provide these kids with safe, clean and convenient access to schools and other services. And to do so in a sustainable way. Therefore, to help the cities of Dushanbe and Bishkek achieve this goal, we are working to develop a comprehensive approach for public transport improvement which takes into consideration regulatory framework, contracting arrangements, fare structure and service planning, as well as land use.

The work is conducted under the advisory services and analytics on Urban Mobility in Central Asia, supported by the Mobility and Logistics Multi-Donor Trust Fund.

Join the Conversation