Do Sub-Saharan African countries need a home-grown tax system?

Do Sub-Saharan African countries need a home-grown tax system?

To reduce poverty and boost shared prosperity, Sub-Saharan African countries need to urgently close two critical gaps—the human capital gap and the infrastructure gap. The human capital gap constrains Africa to only 40% of its potential. Africa’s gross domestic product (GDP) per worker could be 2.5 higher if everyone reached the benchmark of complete education and full health. The 2017 Africa Pulse suggests that closing the infrastructure gap would boost growth and increase GDP per capita by as much as 2.6% per annum.

Closing these gaps will require substantial amounts of financial resources. The World Bank estimates that Africa’s infrastructure needs exceed $93 billion per year over the next decade. Even with increased efficiency in spending, the region’s governments would need to generate about $20 billion of fiscal revenues for investment in infrastructure. The World Bank’s push to increase financing for human capital in Africa to $15 billion for the 2021-23 period is an indication of the order of magnitude of the financing gap.

But more borrowing by governments is neither a feasible nor sustainable option for closing such large gaps with Africa’s rising debt (Figure 1) and many countries already at high risk of debt distress.

Figure 1: Africa: Central government debt and total debt service

Domestic resource mobilization is key

New revenues, raised equitably and spent efficiently, can enhance the lives of citizens by financing better healthcare, schools, sanitation systems and social safety nets for the poorest. Through a combination of legislation, stronger tax administration and more effective taxpayer registration and compliance, Rwanda increased revenues by nearly 50% between 2001 and 2013. This enabled the government to double spending on health from 3.2 to 6.5% of GDP.

But Africa’s current tax system has not and cannot deliver needed revenues

The weak link is that domestic revenue mobilization is too low. Tax revenues averaged only 17.2% of GDP in African countries compared with 22.8% in Latina America and Caribbean countries and 34.2% in OECD countries in 2017. Why? African countries are applying a tax system—borrowed from developed countries—ill-suited to African economies where informality is high, and imports consist mainly of the basics such as food and fuel, and therefore difficult to tax.

Informality mutes the efficiency of an ill-adapted tax system

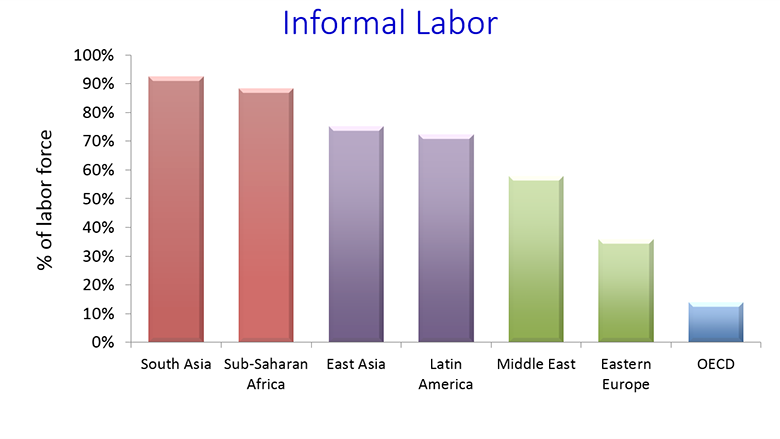

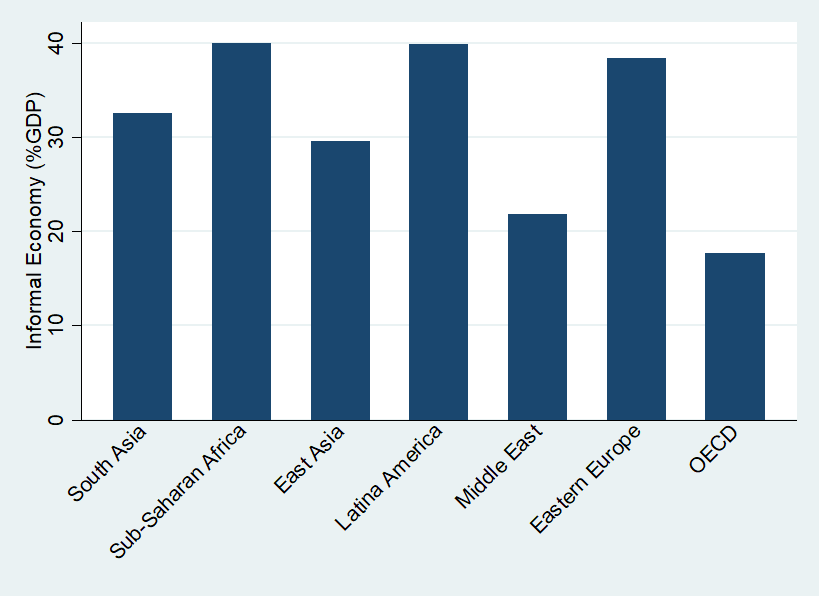

In SSA, almost 90% of the labor force is in the informal economy vs less than 15% for OECD countries (Figure 2). In addition, the informal economy is almost 40% of GDP in SSA, compared to just 18% of GDP in OECD countries (Figure 3).

Figure 2: Informal labor in the economy

Figure 3: Informality is high in Africa (1991-2015)

Sub-Saharan Africa needs a home-grown tax system to unleash the potential of its own fiscal resources. Such a system could be built on two pillars:

- Trust between government and taxpayer—a strong social compact

Recent research suggests the existence of strong non pecuniary drivers of tax compliance, such as tax morale. Trust in governments and institutions significantly impact the willingness of citizens to pay taxes. The low level of tax compliance in Africa stems from the low degree of trust in governments and tax authorities. According to the Afrobarometer 2016 report, tax authorities are the second least trusted institutions in Africa.

A recent World Bank working paper highlights four key dimensions of trust: (i) fairness, (ii) equity, (iii) reciprocity and (iv) accountability. This captures the extent to which: (a) tax systems are fairly and competently designed and administered (“fairness”); (b) burdens are equitably distributed, and everyone pays their share (“equity”); (c) tax revenues are translated into reciprocal publicly provided goods and services (“reciprocity”); and (d) governments administering tax systems are accountable to taxpayers (“accountability”).

- Disruptive technology to unleash the potential of informal sector

The informal sector in Africa covers 90% of the labor force and almost 40% of GDP. In this situation, the traditional tax system is neither efficient nor equitable in the collection of taxes. However, thanks to big data and fintech as well as the high level of mobile penetration, African governments have an opportunity to build their own efficient, equitable and sustainable tax system. There were 456 million unique mobile subscribers in SSA in 2018 and by 2025, the region will receive an additional 167 million subscribers, representing 50% of penetration rate. Governments could, following the example of India, use biometrics to build a consolidated database of potential taxpayers.

The development of mobile banking could facilitate tax collection, lower cost and reduce corruption. More than 395 million mobile accounts have been registered in Sub-Saharan Africa—nearly half of total global mobile money accounts in 2019. In Kenya, the money-transfer system M-Pesa transformed tax policy and administration.

Key elements of a home-grown tax system

- Low rates of presumptive tax for businesses in the informal sector;

- Strong incentives to attract businesses into the digital economy;

- Low cost of mobile banking to facilitate transactions;

- Enhanced cybersecurity to protect personal information and build confidence in the digital economy.

In the face of declining aid flows and rising debt, Africa’s best hope for closing its human capital and infrastructure gaps is to substantially increase domestic resource mobilization. To do so, the region needs to develop its own tax system—one better suited to African economies with their inherent high levels of informality.

Join the Conversation