Furniture makers prize mukau wood in a small town in Kenya's Eastern Province. Photo: Flore de Preneuf / World Bank

Furniture makers prize mukau wood in a small town in Kenya's Eastern Province. Photo: Flore de Preneuf / World Bank

The last 10 years have been rough for many countries in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA): Following a decade-and-a-half of turbocharged growth between 1999 and 2014, when growth on the continent averaged 5% a year and poverty decreased from 57% to 38%, growth faltered, and per capita GDP levels were lower in 2022 than in 2014, raising fears of another lost decade.

Parallel to this growth slowdown, poverty reduction weakened. Though comprehensive figures are not yet in, the number of people living below the poverty line is projected to have increased on the continent, even though, encouragingly, poverty rates are projected to be marginally lower now than before the pandemic.

However, even during SSA’s strong growth period, which gave rise to the “Africa Rising” narrative, there was already concern that strong rates of economic growth were not resulting in equal improvements in living conditions for ordinary people. The UN’s Development Programme, for instance, noted the Poverty-reducing power of growth is low in Sub-Saharan Africa. Similar statements can be found here and here among others.

In short, there is widespread concern that economic growth in Sub-Saharan Africa is not sufficiently translating into poverty reduction . Or, in technical terms, that the “growth elasticity of poverty”—the percent change in poverty for a one percent change in GDP per capita—is lower in SSA, relative to other regions.

Economic growth in SSA is less poverty reducing

Our new paper aims to empirically test this hypothesis. Building on the work by World Bank Economist Martin Ravallion (1952–2022) and others, we create a database of “spells” by combining each pair of consecutive and comparable household surveys within a country, arriving at a database of just over 1,604 spells.

As we are interested in estimating the association between economic growth and poverty (as measured by the Bank’s $2.15-a-day line) in countries that still have poverty, we remove spells with poverty rates below 2%, largely excluding countries in North America and Western Europe. Our final sample consists of 575 comparable spells between 1981 and 2021, based on 715 nationally representative household surveys for 89 countries, representing over 92% of the population in the “developing world”.

The analysis indeed suggests that the extent to which economic growth translates into poverty reduction is lower in SSA, even after differences in initial characteristics are accounted for. In the overall sample, the estimated elasticity between growth in GDP per capita and poverty reduction is 2.5 (indicating that a one percent growth in GDP per capita has on average been associated with a 2.5 percent reduction in the poverty rate). However, in SSA it is only half that (the growth elasticity of poverty reduction is 1).

To a large extent, however, this pattern could be expected: Countries with high initial poverty rates (many of which are in Africa) tend to have mechanically lower passthroughs between economic growth and poverty reduction. To avoid this bias, our analysis mainly focuses on the elasticity between growth in GDP per capita on the one side and growth in per capita household consumption (as measured by surveys) on the other, which does not suffer from the same base effects.

The findings, however, hold: Economic growth in SSA benefits households substantially less. While the elasticity between economic growth and household survey consumption growth is about one in the overall sample (meaning that a one percent growth in GDP per capita is on average associated with a one percent increase in household consumption), in SSA it is only half of that.

African economies would thus need to grow faster to achieve similar improvements in the monetary welfare of households, which, in the current external environment, is a tall order.

The logical follow-up question is: Why is the association between aggregate economic growth and household welfare lower in Sub-Saharan Africa?

Our paper tried to shed some light on this by identifying the factors that affect the extent to which economic growth translates into household consumption. With the important caveat that these are associations and not causal effects, the results highlight the importance of getting the basics right: Basic human capital services and key basic infrastructure amplify the extent to which economic growth lifts household welfare.

Higher rates of primary and secondary school enrolment and youth literacy increase the passthrough between economic growth and household welfare, as do electrification and more universal access to safe drinking water and basic sanitation. In contrast, the prevalence of violent conflicts or civil wars and higher dependence on some natural resources inhibit the welfare-increasing effect of growth.

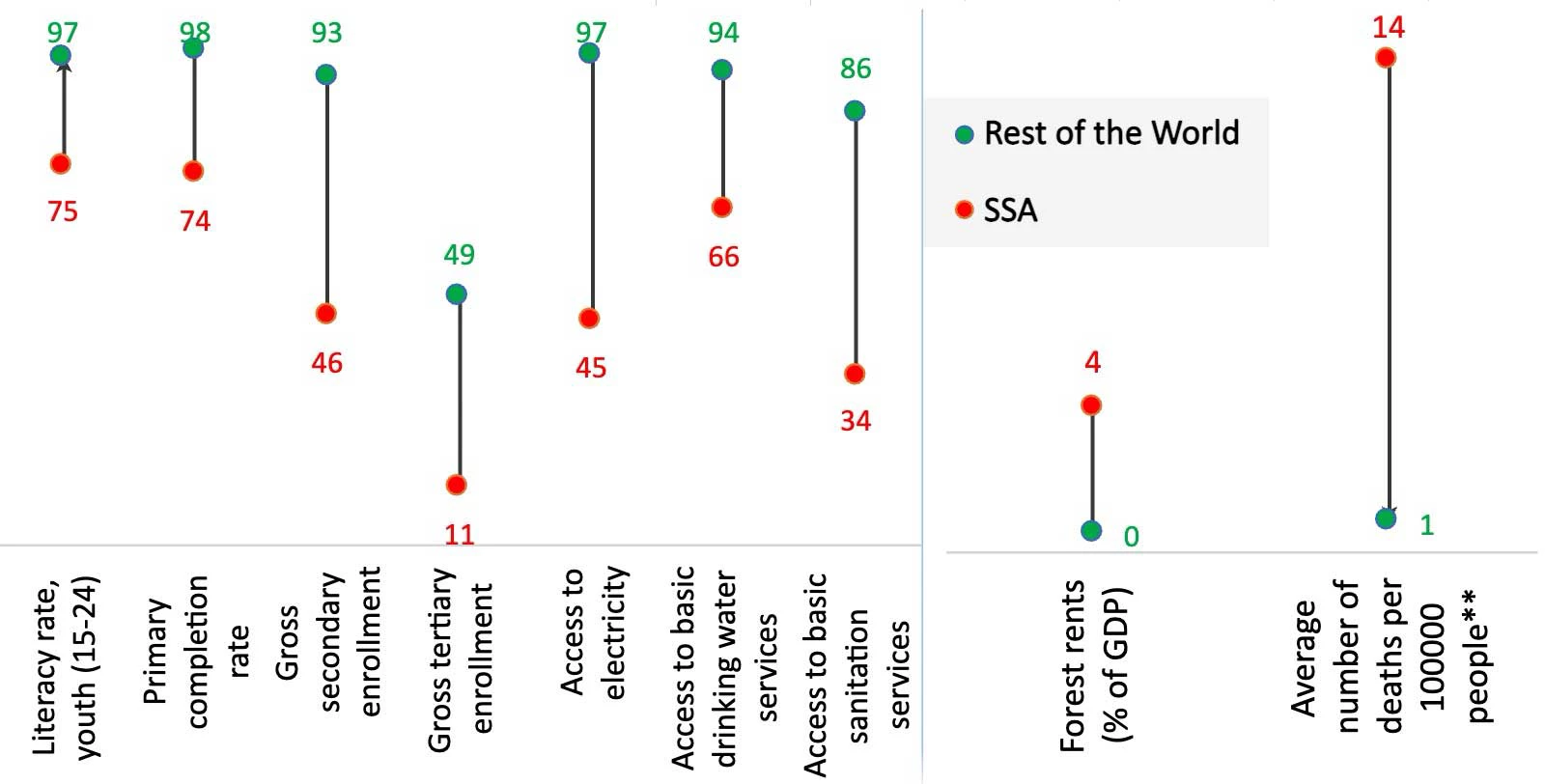

In general, variables that amplify the effect of economic growth on household welfare are scarcer in African countries, as shown in Figure 1 below, while variables that inhibit the poverty-reducing effect of growth are more abundant—likely explaining, in part, the lower effect of economic growth in lifting household welfare.

Figure 1. Simple averages of selected development indicators for Sub-Saharan Africa and the rest of the world in circa 2019*

To renew poverty reduction and attain improved living conditions for its people, reigniting sustainable economic growth is a key priority for Sub-Saharan Africa. Indeed, our results show that elasticities have not changed through time, meaning that the recent slowdown in poverty reduction is largely due to the slowdown in growth. However, reigniting growth will not be enough: Even with renewed growth, a bigger bang for the growth buck can only arguably be attained. And improved provision of basic human capital services and basic infrastructure can play, according to our results, an important role in that.

Join the Conversation