The Future of Work in Africa: Making Productive Investments for More and Better Jobs

The Future of Work in Africa: Making Productive Investments for More and Better Jobs

There are uncertainties and misconceptions about the impact of digital technologies on the future of work. Will robots replace humans in the work place? Will digital technologies create a new “digital divide” and widen inequalities between the higher-educated connected and lower-educated unconnected people? Will new opportunities open up for African countries to create jobs, improve incomes, reduce poverty and climb up the development ladder?

These are some of the questions our new report on the Future of Work in Africa addresses. We argue that African countries have the potential to take advantage of digital technologies in ways that are different from other regions of the world. However, to take advantage of this opportunity to secure a better future for all people in African countries, certain investments must be prioritized. Governments need to invest in better policy-making to promote competition, to help build worker and entrepreneurship skills, to help increase the productivity of informal enterprises, and to expand social protection. This will unleash businesses to do what they do best: investing in more and better jobs.

The limitations and promise of digital technologies in Sub-Saharan Africa

Digital technologies are disrupting various industries—from manufacturing and financial services to retail and hospitality—by transforming the business models of firms and reshaping the skills needed for work. Think about it. Amazon and Airbnb are out-competing traditional brick-and-mortar companies like retail stores and hotels. However, as the World Development Report 2019 notes, threats to jobs from technology are exaggerated and are not uniform across the world. While advanced economies are shedding industrial jobs, industrial employment is rising in parts of East Asia and stable in others.

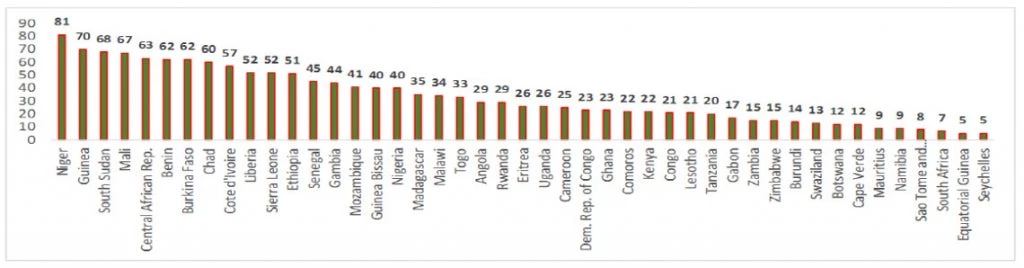

Sub-Saharan Africa is characterized by a range of challenges that may appear to be limiting factors preventing the adoption of digital technologies to have a positive impact. African countries have very low levels of human capital for a young and fast-growing population, as highlighted by Figure 1. Notably, more than 60 percent of the labor force is made up of ill-equipped adults who need jobs. The region has a particularly large informal sector that is distinct from other developing regions in size and composition. The informal sector accounts for almost 90 percent of total employment, especially in the agriculture sector. It is comprised of both small and large firms. Lastly, the social protection systems in Sub-Saharan Africa are insufficient and inefficient. About 8 in 10 Africans are not covered by any safety net, are not enrolled in a pension plan, and are not covered by any other social protection program. Disruptions to labor markets by digital technologies as well as climate shocks, fragility, accelerating economic integration, and population transitions will create more social protection needs.

Figure 1: In most Sub-Saharan African countries, a large share of adults ages 15+ are illiterate

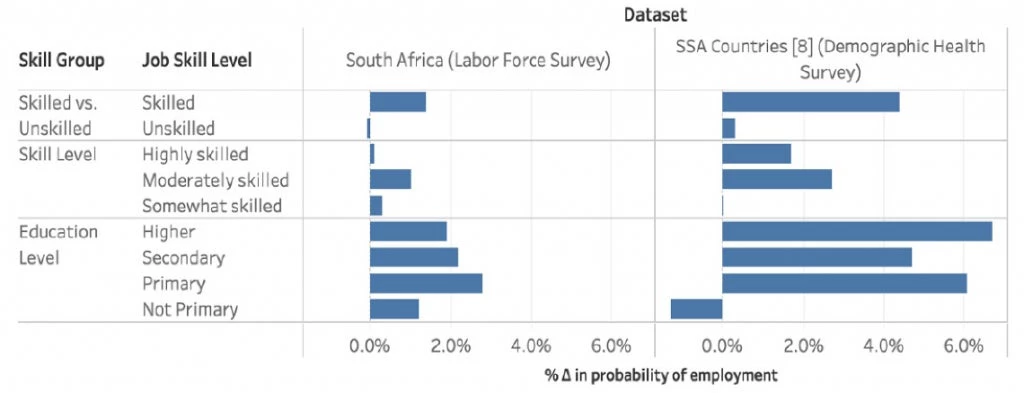

In spite of these development challenges, we believe that the future of work could be bright. Since Africa has a much smaller manufacturing base than other regions, automation is not likely to displace many workers in the coming years. Most African economies still have low levels of demand for products that are commonplace in other parts of the world, such as televisions and refrigerators. Therefore, the cost and price reductions from technology adoption are more likely to help firms grow, create more jobs, and produce more affordable products—to the extent that they can be made by Africans. Finally, technologies designed to meet the productive needs of African workers with limited education have the potential to help them learn more and earn more. A recent study has shown that, following the arrival of faster internet in Sub-Saharan Africa during the late 2000s and early 2010s, the increase in the jobs rate was similar for those with primary schooling as for those with secondary and tertiary schooling (Figure 2). This is an optimistic finding. It will require additional evidence to be built based on a broader range of relevant datasets to better inform policy-making in this area.

Figure 2: Faster internet access increased employment of workers across educational levels in available datasets

The productive investments necessary to secure the future of work for Africans

To reap the benefits of digital technologies, African governments, development partners, businesses and other stakeholders need to prioritize investments in at least three critical areas. First, governments should invest in better policy-making to build worker and entrepreneurship skills. Among others, they need to put in place a business environment that enables inventors and entrepreneurs to develop the digital tools needed to boost the productivity of both the stock of low-skilled workers and those workers undertaking the new tasks that adoption of new technologies will enable. This should complement increased investments in early childhood education and health care service delivery.

Second, African governments and other stakeholders should invest in creating a business environment that helps boost the productivity and upgrade the skills of informal businesses and workers. Digital technologies can be leveraged to this end, to increase access to markets, including markets for information, input purchases and output sales, and credit. Public policies that aim to achieve formalization should focus on larger informal firms that aggressively compete with and distort the incentives of formal firms.

Third, governments should increase public investments to extend social protection coverage. This can be achieved by improving revenue collection, using public expenditure reviews to justify the need for rebalancing government spending towards social protection and labor systems, and more effectively coordinating development assistance. To make better use of finite resources and overcome the political resistance that can often accompany safety nets for the poor, social protection should be part of broader national economic strategies on jobs and economic transformation, rather than stand-alone initiatives. Investments in productivity-increasing safety nets, such as the Sahel Adaptive Social Protection program can be linked to a broader strategy to provide regional public goods in an era of increased integration.

Digital technologies can have an important role to play in improving the future of work in Africa. However, it will depend on the right complementary investments being made.

Join the Conversation