In the 10-11 age group, the top three places went to teams from destitute neighborhoods, including Kibera, which some people have (wrongly) dubbed as the world’s largest slum. Kibera Sports Academy stood at the top of the podium, while second and third places went to Inspiration Kenya and Peace Academy respectively.

Many people, including Kenyans, consider slums the epitome of misery. The common wisdom is they breed disease, crime and many other forms and manifestations of poverty. Why then are slums growing bigger, with people migrating to them in ever increasing numbers?

The short answer is that most people, on balance, prefer urban poverty to rural misery. Or, as Ed Glasser — the author of Triumph of the City — puts it: “Cities don’t make people poor – they attract poor people”.

For the poor, there are many advantages to urban life. Most important, there are more job opportunities. It’s also easier to get around in the cities without a car, which poor people typically don’t own. Matatus may drive other motorists crazy, but they provide an important service for the poor and the emerging middle class: because so many urban Kenyans depend on them, they are always full, and offer regular services. The economic concept of “economies of scale” (it’s cheaper to produce for a large market) also applies to services, beyond transportation, which tend to be better and cheaper in towns. Think of electricity: it is obviously much easier to connect one million urban residents, than one million people scattered over 10,000 villages across the country.

With rapid population growth, cities are bound to still grow larger, and because poor migrants can’t afford middle class housing, slums will be part of the picture, especially in Africa. But this does not mean that Africa’s cities are too big. On the contrary, they are probably still too small, compared to other parts of the world. With a population of 3.5 million, Nairobi is only one-tenth the size of Tokyo, the world’s largest city, and Mombasa (less than a million residents despite its auspicious location) does not even make the top 500 of the world’s largest cities.

But isn’t small beautiful? Not if you are trying to make your cities engines of growth. There is ample evidence, from around the world, that the most efficient growth engines are large cities, where businesses find their suppliers and their markets in close proximity to themselves. For growth, big cities are beautiful—provided that these bigger cities provide the services that businesses and residents need.

Of course, this does not change the fact that life in slums is often miserable. Slum dwellers are exposed to unpredictable hazards, as we were all reminded last September, when almost 100 people died from a pipeline fire in Sinai, close to Nairobi’s industrial area. Simply ignoring the plight of people leaving in slums cannot be the solution. Instead, slums need to be upgraded—as many cities around the world have successfully done. Almost all rich cities—including London, Berlin and New York, once had slums with extremely poor public services. Singapore is the most recent global city to transform its slums, in its effort to move rapidly from “Third World to First”. The Government of Singapore developed a master-plan, and strong regulations around land use. It provided legal certainty, developed a strong capacity to follow through on its regulations, punishing violations, and invested heavily in infrastructure (water, electricity) and social facilities.

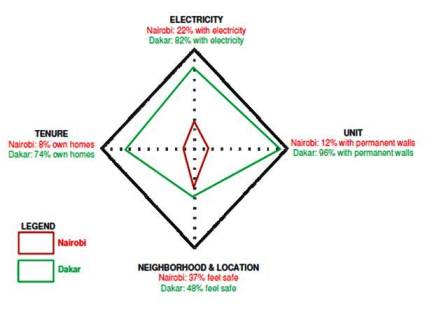

Much can be done here and now. A key factor is land ownership. Research from my colleague Sumila Gulyani and her co-authors Debabrata Talukdar and Darby Jack shows that living conditions can vary enormously across different slums, even when average incomes are similar. Take Nairobi and Dakar. Both are capital cities and regional hubs with comparable overall wealth. Yet in Dakar more than 80 percent of slum dwellers have access to electricity, while in Nairobi only 22 percent do (see figure) —even though slum-dwellers in Nairobi have higher levels of education and are more likely to hold a job than their peers in Dakar!

Figure: Living Conditions Diamond, Nairobi and Dakar (click to see it larger)

Source: Visualization adapted from Gulyani, Talukdar, Jack, 2010

What is going on here? The main reason for the difference, it seems, is that Dakar’s slum residents have security of tenure and often own the land, so they have an incentive to invest in their property, and access utilities like water and electricity. By contrast, nine in ten of Nairobi’s slum dwellers are tenants with very limited tenure rights, and so neither they nor their landlords have incentives to invest in improvements. Learning from Singapore, Kenyan cities would benefit from a clear policy which strengthens the tenure rights of slum dwellers: investments in their properties would surely follow.

A few weeks ago, a local NGO invited me to share some ideas with middle-level students in Kibera, who are part of a special education program which runs every Saturday. These children’s dreams and hopes are similar to those of children everywhere. They want to become accountants, lawyers, engineers, and soccer players. Most poor families don’t need charity or special treatment. They have the talent to compete with everyone, and not only in football. They just need opportunities to do so, including a level playing field to show their skills. Being closer to a city is helping them to get there, but having a clear policy to upgrade slums is the next critical step.

Follow Wolfgang Fengler on Twitter@wolfgangfengler. This article is also been published by Kenya’s “Saturday NATION” in the column “Economics for Everyone”

Join the Conversation