The World Bank (WB) has set an ambitious goal of securing universal access to formal financial services by 2020. Although 700 million people have signed up for a bank account since 2011, about two billion worldwide remain unbanked. As the WB seeks to expand worldwide financial inclusion, it should look to Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) for inspiration.

In the developing world as a whole, 54% of adults have an account – up 13 percentage points since 2011, according to the Global Findex database. The vast majority of that growth came from people opening accounts at banks or other financial institutions.

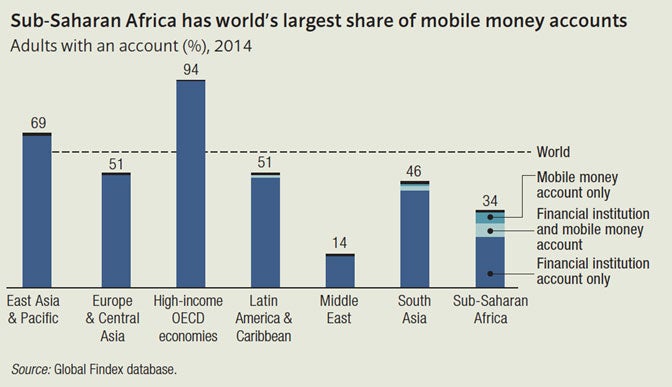

Sub-Saharan Africa is the only developing region to defy this trend. In part, by harnessing mobile money technology, through mobile money service accounts and the increase in bank agents that use mobile phones to reach rural clients, SSA drove up account ownership by a third – to 34%. Overall, 12% of adults in the region have a mobile money account, which is four times the developing world average (figure 1 and map 1).

Figure 1

Map 1

This matters because accounts are a first entry point into the formal financial system, and without them, people are left to transact in ways that are often risky, wasteful, and inconvenient. Parents squander time waiting in line to pay their children's school fees in cash. Entrepreneurs turn to lenders who charge usurious rates. Cash savings get stuffed under a mattress.

Accounts help people take control of their financial lives by offering better ways to manage money. As the Findex team shows in its new policy note, SSA stands out for the high usage of accounts for payments and savings. Just 11% of accounts in the developing world are used to both make and receive payments. In SSA, that figure is 35% – close to the share in rich OECD countries and way ahead of all developing regions. Meanwhile, 42% of account owners in SSA use their account to save money. The only developing region with a higher rate is East Asia and the Pacific.

The picture isn't entirely rosy. A big drawback to SSA's progress is that it's not widely shared. Gender inequality is the norm in most of the region: just 30% of women have an account, compared to 39% of men. There's also a big divide between rich and poor. About a quarter of adults in the poorest 40% of households own an account, against 46% of those in the richest 60%. Account ownership is three or four times higher among the rich in several countries, including Angola, Rwanda, and Zimbabwe. SSA is hardly unique in this respect, as comparable gender and income gaps are found in the developing world as a whole.

We've seen that mobile money technology is deepening financial inclusion. But can it close the account ownership gaps in gender or income? So far, the evidence is mixed. It's helping in Kenya and Côte d'Ivoire. Among adults who have financial institution accounts, there are deep inequalities between men and women; rich and poor; and the young and the elderly. However, there are no such gaps among adults who only have mobile money accounts.

The same doesn't hold elsewhere. In Tanzania, there's a gender gap among those who only use mobile money, but not for those using financial institution accounts. Uganda struggles with gender and income gaps in both categories of account ownership. Looking at the region as a whole, the gender gap is, if anything, slightly higher among mobile money users.

The Global Findex team's new policy note on mobile money reveals huge opportunities to build on Sub-Saharan Africa's financial inclusion progress. Regionally, 350 million adults lack an account. Of them, 155 million say they have their own mobile phone, while 200 million say they have access to one at home. Most are located in West Africa, where mobile money has yet to take off, but 40 million live in East Africa, home to the world's highest mobile money account ownership rates.

Governments and businesses could help bring tens of millions of adults into the financial system if they stopped making routine payments in cash. Digitizing payments for agricultural goods could cut the number of unbanked by about 125 million, including up to 16 million in Nigeria. Some countries are already moving in this direction. In Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda, more than 10% of adults receive agricultural payments into accounts, often including mobile money accounts.

In some ways, then, the answers to Africa's formidable financial inclusion problems are implied by the progress that's already been made. By taking advantage of new technologies, and offering products that are cheaper and more convenient than cash, the region presents the world with lessons for expanding financial access. Development practitioners would do well to take notice.

For more information on the Global Findex: www.worldbank.org/globalfindex

Join the Conversation