This blog originally appeared in French in

HuffPost Maghreb.

“

Tunisia was the first country to develop the pharmaceutical industry in Africa ,” said Inès Fradi, Director General of Tunisia’s Pharmacy and Medicines Directorate (DPM), recently. “We were among the pioneers in this field, and it is high time to move on to make this industry an engine for growth and development.” This strong message demonstrates the awareness that exists among public and private stakeholders of the need to accelerate the development of Tunisia’s pharmaceutical industry and boost its competitiveness.

“

Tunisia was the first country to develop the pharmaceutical industry in Africa ,” said Inès Fradi, Director General of Tunisia’s Pharmacy and Medicines Directorate (DPM), recently. “We were among the pioneers in this field, and it is high time to move on to make this industry an engine for growth and development.” This strong message demonstrates the awareness that exists among public and private stakeholders of the need to accelerate the development of Tunisia’s pharmaceutical industry and boost its competitiveness.

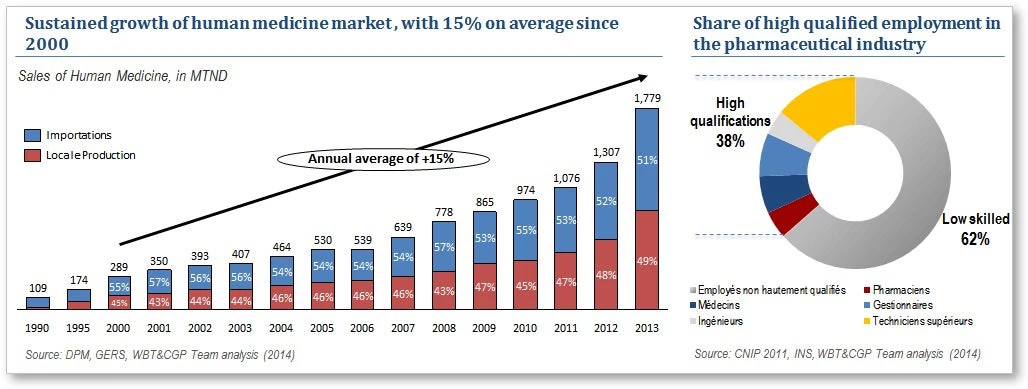

With good reason. The results of an assessment of the sector’s competitiveness, conducted by the World Bank Group (2014), highlighted the strengths of the pharmaceutical sector in Tunisia, but also revealed the constraints currently hindering its development. According to the study, the pharmaceutical industry in Tunisia has grown at an average annual rate of 15% — much higher than the global average. The industry meets 49% of the country’s need for medicines (mainly generics) and employs more than 6,000 people, 38% of whom hold skilled jobs with average salaries that are among the highest in Tunisia.

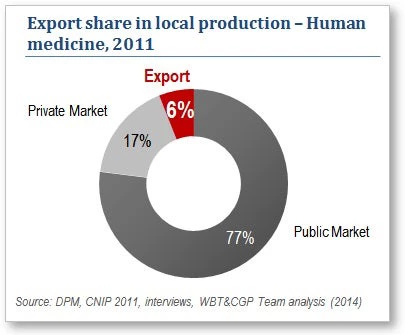

Despite these positive indicators, and a growth phase that has made it possible to meet local demand, the industry does not appear to have fully realized its potential. It has not opened up enough to foreign markets and, as a result, Tunisian exports of human medicines account for only 6% of local manufacturing —13 times less than in comparable countries such as Jordan.

A new approach is needed to make the Tunisian pharmaceutical industry more competitive on world markets. The industry needs to export more and better medicines, gaining a foothold in foreign markets by targeting strategic markets where quality trumps price, but also developing a range of biotechnology-derived products, which are the new focus of the sector.

But this shift cannot occur without a more sustained effort to bring the regulatory and institutional framework up to international standards. Important reforms are still pending. These reforms are vital to fuel the growth of this high-value-added industry and are necessary and will be beneficial for public health.

It was that conclusion that prompted the Tunisian pharmaceutical sector to launch a public-private dialogue (PPD) more than a year ago. PPD is a participatory and inclusive process in which a variety of public and private stakeholders come together to develop new economic policies. It is part of a new culture of dialogue that has taken root in Tunisia in an effort to build resilience, not only at the national level (following Tunisia’s receipt of the Nobel Prize), but also at the sectoral level as a means of spurring economic growth and tackling the challenge of employment.

It was that conclusion that prompted the Tunisian pharmaceutical sector to launch a public-private dialogue (PPD) more than a year ago. PPD is a participatory and inclusive process in which a variety of public and private stakeholders come together to develop new economic policies. It is part of a new culture of dialogue that has taken root in Tunisia in an effort to build resilience, not only at the national level (following Tunisia’s receipt of the Nobel Prize), but also at the sectoral level as a means of spurring economic growth and tackling the challenge of employment.

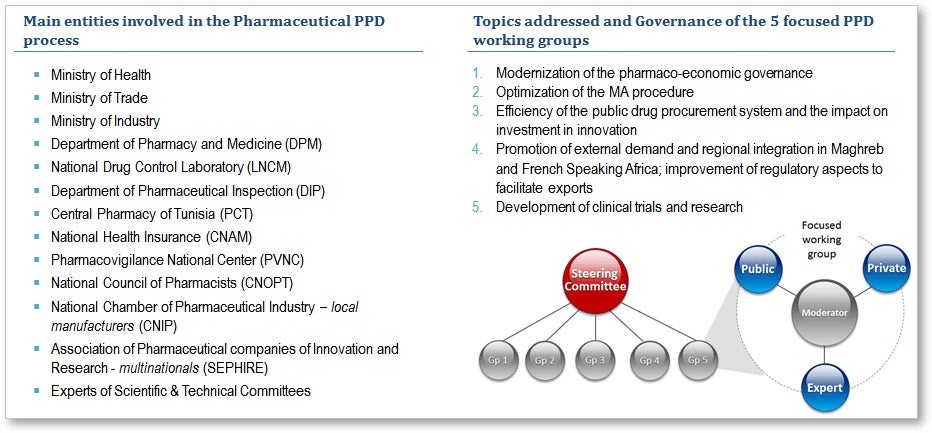

The first phase of this sectoral PPD has helped to prioritize the main constraints to competitiveness for the pharmaceutical sector. The identification of these priorities led to the forging of a common vision, and the formation of five public-private working groups to carry out the second phase of the PPD—the development of action plans. The dynamic role of Tunisia’s directorate, the DPM, and the involvement of representatives of the private sector, such as the national chamber of pharmaceutical Industries and the association of pharmaceutical companies engaged in research and development, have been key to the success of this process, which has been facilitated by the Bank. The full engagement of stakeholders has resulted in more than 40 high-level, public-private meetings involving some 15 institutions, including three government ministries, various public health authorities, and two associations of pharmacy-sector professionals.

Today, the sector is beginning to reap the rewards of the working groups’ efforts. The first initiatives envisaged are being implemented this year. The work of the group on optimizing marketing authorization procedures has advanced rapidly, and the reforms resulting from this participatory process were presented publicly by Tunisia’s Ministry of Health during a workshop. As marketing authorization procedures have always been a major concern for the public sector, and a major constraint to private-sector development, this is an important step forward facilitated by the PPD.

Other initiatives are also in the pipeline. The working group responsible for the development of pharmaceutical exports, for example, has put together scenarios for the period up to 2030 and is exploring target export destinations for which political and diplomatic support could be given.

If the PPD adventure continues in the pharmaceutical sector, and is eventually extended to other value chains to make Tunisia a platform of choice for health products and services, its success could produce a significant effect. Several other economic sectors in Tunisia could replicate this process, in which the consensus and conviction of stakeholders have given rise to an effective economic development alternative.

“

Tunisia was the first country to develop the pharmaceutical industry in Africa ,” said Inès Fradi, Director General of Tunisia’s Pharmacy and Medicines Directorate (DPM), recently. “We were among the pioneers in this field, and it is high time to move on to make this industry an engine for growth and development.” This strong message demonstrates the awareness that exists among public and private stakeholders of the need to accelerate the development of Tunisia’s pharmaceutical industry and boost its competitiveness.

“

Tunisia was the first country to develop the pharmaceutical industry in Africa ,” said Inès Fradi, Director General of Tunisia’s Pharmacy and Medicines Directorate (DPM), recently. “We were among the pioneers in this field, and it is high time to move on to make this industry an engine for growth and development.” This strong message demonstrates the awareness that exists among public and private stakeholders of the need to accelerate the development of Tunisia’s pharmaceutical industry and boost its competitiveness.

With good reason. The results of an assessment of the sector’s competitiveness, conducted by the World Bank Group (2014), highlighted the strengths of the pharmaceutical sector in Tunisia, but also revealed the constraints currently hindering its development. According to the study, the pharmaceutical industry in Tunisia has grown at an average annual rate of 15% — much higher than the global average. The industry meets 49% of the country’s need for medicines (mainly generics) and employs more than 6,000 people, 38% of whom hold skilled jobs with average salaries that are among the highest in Tunisia.

Despite these positive indicators, and a growth phase that has made it possible to meet local demand, the industry does not appear to have fully realized its potential. It has not opened up enough to foreign markets and, as a result, Tunisian exports of human medicines account for only 6% of local manufacturing —13 times less than in comparable countries such as Jordan.

A new approach is needed to make the Tunisian pharmaceutical industry more competitive on world markets. The industry needs to export more and better medicines, gaining a foothold in foreign markets by targeting strategic markets where quality trumps price, but also developing a range of biotechnology-derived products, which are the new focus of the sector.

But this shift cannot occur without a more sustained effort to bring the regulatory and institutional framework up to international standards. Important reforms are still pending. These reforms are vital to fuel the growth of this high-value-added industry and are necessary and will be beneficial for public health.

It was that conclusion that prompted the Tunisian pharmaceutical sector to launch a public-private dialogue (PPD) more than a year ago. PPD is a participatory and inclusive process in which a variety of public and private stakeholders come together to develop new economic policies. It is part of a new culture of dialogue that has taken root in Tunisia in an effort to build resilience, not only at the national level (following Tunisia’s receipt of the Nobel Prize), but also at the sectoral level as a means of spurring economic growth and tackling the challenge of employment.

It was that conclusion that prompted the Tunisian pharmaceutical sector to launch a public-private dialogue (PPD) more than a year ago. PPD is a participatory and inclusive process in which a variety of public and private stakeholders come together to develop new economic policies. It is part of a new culture of dialogue that has taken root in Tunisia in an effort to build resilience, not only at the national level (following Tunisia’s receipt of the Nobel Prize), but also at the sectoral level as a means of spurring economic growth and tackling the challenge of employment.

The first phase of this sectoral PPD has helped to prioritize the main constraints to competitiveness for the pharmaceutical sector. The identification of these priorities led to the forging of a common vision, and the formation of five public-private working groups to carry out the second phase of the PPD—the development of action plans. The dynamic role of Tunisia’s directorate, the DPM, and the involvement of representatives of the private sector, such as the national chamber of pharmaceutical Industries and the association of pharmaceutical companies engaged in research and development, have been key to the success of this process, which has been facilitated by the Bank. The full engagement of stakeholders has resulted in more than 40 high-level, public-private meetings involving some 15 institutions, including three government ministries, various public health authorities, and two associations of pharmacy-sector professionals.

Today, the sector is beginning to reap the rewards of the working groups’ efforts. The first initiatives envisaged are being implemented this year. The work of the group on optimizing marketing authorization procedures has advanced rapidly, and the reforms resulting from this participatory process were presented publicly by Tunisia’s Ministry of Health during a workshop. As marketing authorization procedures have always been a major concern for the public sector, and a major constraint to private-sector development, this is an important step forward facilitated by the PPD.

Other initiatives are also in the pipeline. The working group responsible for the development of pharmaceutical exports, for example, has put together scenarios for the period up to 2030 and is exploring target export destinations for which political and diplomatic support could be given.

If the PPD adventure continues in the pharmaceutical sector, and is eventually extended to other value chains to make Tunisia a platform of choice for health products and services, its success could produce a significant effect. Several other economic sectors in Tunisia could replicate this process, in which the consensus and conviction of stakeholders have given rise to an effective economic development alternative.

Join the Conversation