In the build up to the Arab uprisings, data was doing its part to deceive those who follow the region closely. Tunisia and Egypt provide great examples. Both nations closed the first decade of the century implementing the kind of classic economic reforms often praised by western-based multilateral and international organizations. Extremely qualified, intelligent and well-meaning experts on both countries took an objective look at reforms, GDP trajectories and other traditional metrics, such as infant mortality rates, poverty reduction, etc., and concluded that these countries, while not perfect, were moving forward along a path of increasing correction. A few weeks later, both nations were in complete political upheaval.

In the build up to the Arab uprisings, data was doing its part to deceive those who follow the region closely. Tunisia and Egypt provide great examples. Both nations closed the first decade of the century implementing the kind of classic economic reforms often praised by western-based multilateral and international organizations. Extremely qualified, intelligent and well-meaning experts on both countries took an objective look at reforms, GDP trajectories and other traditional metrics, such as infant mortality rates, poverty reduction, etc., and concluded that these countries, while not perfect, were moving forward along a path of increasing correction. A few weeks later, both nations were in complete political upheaval.

At Gallup, in 2005, we built a series of metrics that more granularly highlight for world leaders and research organizations how the human condition is experienced on its many platforms. One of the most basic but important metrics we developed for the World Poll is the Cantril Self-Anchoring Striving Scale. Gallup classifies respondents as thriving, struggling or suffering according to how they rate their current and future lives on a ladder scale with steps numbered from zero to 10. Those who rate their present life a seven or higher and their life in five years an eight or higher are classified as thriving, while those who rate both dimensions a four or lower are considered suffering. Respondents whose ratings fall in between are considered struggling.

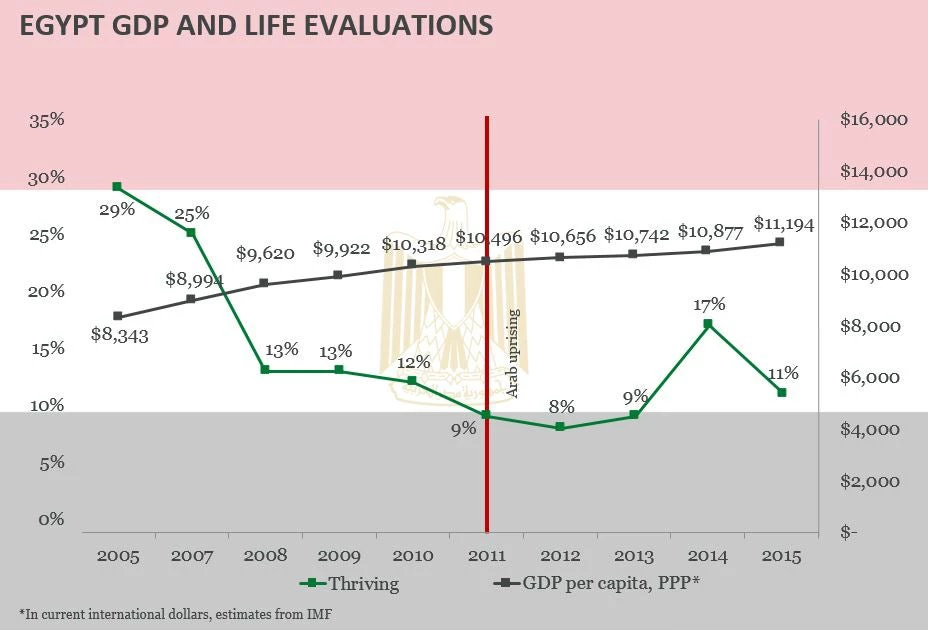

What we saw in both Egypt and Tunisia, as well as in other countries who witnessed unrest including Bahrain and Syria, with this behavioral metric was the reality masked by GDP per capita trends and other classic economic metrics. In fact, in the years leading to the unrest, while trends of traditional metrics could be best described as “ uneventful, with a slight uptick,” life evaluation data were telling a clear and consistent story in Tunisia, Egypt, Yemen and Bahrain. The general theme of those data were, “‘ Warning, contents under pressure. Do not shake!” This was due to the clear decline in how citizens themselves were evaluating their lives. It was apparent that far too many saw the future as bleak, irrespective of GDP or what other classic metrics said about their countries.

For three years before the MENA region politically exploded, part of my job was to tour that region, country by country, and brief ministers and their staffers. I shared data from portfolios that covered topics on labor, youth, security, foreign relations, development and so on to share data findings from World Poll surveys conducted in their respective countries. Almost everyone I met had the same reaction to behavioral metrics: These are interesting findings, but we need “real metrics” to follow what is really happening in our society. One memorable briefing was littered with the repeated declarations that, “We need data on how to create jobs,” as though the jobs would just pop out of the excel sheet.

Despite their misleading nature in the lead up to the Arab uprisings, valid and reliable classic metrics are absolutely a critical tool for anyone trying to follow the progress of societies in the region. The challenge is that the useful scope of those metrics is often exaggerated or extrapolated to mean more than any one metric was designed to. In Egypt and Tunisia, these metrics were seen as sufficient for measuring social progress at large. This is despite the fact that GDP per capita, for example, was never intended to serve as a proxy for socio-political evaluations.

For leaders and researchers alike, a critical goal for the next five years is to develop more valid, revealing and reliable metrics that enable us to look more precisely at how societies in the region are doing. Due to the turbulent realities unfolding in the region, this issue is now of the highest importance for all actors, particularly national and local leaders within the region, not just researchers.

The reality is this: some of the most useful data one can gather is to ask people about what they are truly experts on -- their own lives. Continuing to use macroeconomic and other classic metrics as proxies for societal health is an error we no longer have the luxury of making in this region.

Copyright Standards

This document contains proprietary research, copyrighted materials, and literary property of Gallup, Inc. It is for the guidance of your company only and is not to be copied, quoted, published, or divulged to others outside of your organization. Gallup® is a trademark of Gallup, Inc. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners. This document is of great value to both your organization and Gallup, Inc. Accordingly, international and domestic laws and penalties guaranteeing patent, copyright, trademark, and trade secret protection protect the ideas, concepts, and recommendations related within this document. No changes may be made to this document without the express written permission of Gallup, Inc.

Join the Conversation