Farm fields in Egypt

Farm fields in Egypt

The year 2022 will be remembered as one of soaring inflation, posing development challenges both to advanced and emerging markets. One such challenge stems from the rise in the price of food items, which led to increased food insecurity across the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. The latest World Bank Economic Update for the MENA region shows how even temporary spikes in food inflation can have a long term, negative impact on the development and economic futures of newborns and young children.

What’s clear is that food insecurity is both a humanitarian and an economic concern, putting tomorrow’s youth on paths of limited prosperity and preventing the region from realizing its full economic potential. Simply put, even if the food inflation of 2022 turns out to be short-lived, the destinies of today’s children have been altered, nonetheless.

Inflation hits the poor much harder than the rich due to the disproportionate share of family expenditures to food. Average year-on-year food inflation between March and December 2022 was 29% in the MENA region, which is far higher than headline inflation of 19.4%. Food price inflation reached double digits for most of the developing MENA economies in 2022. Poorer households in December 2022 experienced inflation that was about 2 percentage points higher than that of rich households on average across developing MENA countries. This pattern holds for each of the developing MENA countries.

There is mounting evidence that negative shocks can have multi-generational effects on development outcomes in education, health, and income, among other areas. Since the MENA region is young compared to other regions, except sub-Saharan Africa, estimates suggest that about 8 million children under 5 years of age are likely to be severely food insecure in 2023. The report finds that increases in food prices associated with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine may have increased the risk of stunting by 17-24 percent, which translates to 200,000 to 285,000 babies at risk of stunting in developing MENA economies. This entails losses of three weeks to a month of schooling and a 0.5 to 0.8 percent reduction in test scores. Peer reviewed studies suggest that the effects last well into adulthood in terms of lower productivity and may affect their children too.

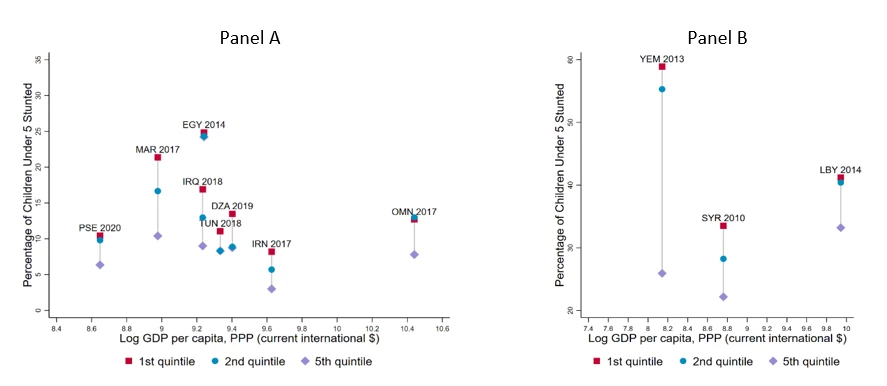

Unfortunately, child health and nutrition were already inadequate before the COVID-19 pandemic. Stunting rates—a measure of the cumulative impact of health deficiencies in a child from pre-birth to age 5—are much higher for many countries in the region relative to their income peers. Furthermore, the gap between the stunting rates of the richest and poorest households in many MENA economies of the region has been historically large (Figure 1). The dietary composition of food for children is limited and the widespread use of subsidies may have distorted household food spending toward items that are less nutritious. This manifests in the double burden of malnutrition – child obesity and undernutrition are prevalent side-by-side in many MENA economies.

Much of the data on child health and nutrition in MENA are dated, however. Only 11 of the 19 economies in the region have taken the relevant household survey since 2015 which means policymakers are flying blind about the health of their children, thus leaving analysts with few alternatives to estimate the incidence of food insecurity in real time.

Through machine-learning model estimates, the report finds that almost one out of five people in MENA is likely to be food insecure in 2023, rising from 11.8 percent in 2006. This is largely due to Syria and Yemen. Figure 2 shows upper-middle-income and lower-income countries in the region largely have food insecurity prevalence rates that are higher than their income peers. Inflation is a big part of the story: across all four MENA subgroups — developing oil importers, developing oil exporters, conflict countries and the GCC — inflation accounts for 24 percent to 33 percent of 2023’s forecasted food insecurity.

The challenge of food insecurity is enormous. According to estimates in this report, the projected development financing needs for the severely food insecure in the MENA region are in the billions of dollars annually. There are advantages to investing in resilience and tackling chronic food insecurity before it escalates into full blown crises. There are also several policy tools that can help alleviate food insecurity. Some policies, such as well-targeted cash and in-kind transfers, can be enacted immediately to stem acute situations of food insecurity. Others may take longer to implement—such as policies aiming to enhance maternity leave, childcare, medical care, and food systems. Importantly, the report finds the region’s data systems are ill equipped to monitor and track the rising threat of food insecurity. The time to act is now. We cannot afford to fail the future generations of the MENA region.

Join the Conversation